History fans who frequent Facebook’s popular history Groups are in for a shock when they next log in. Nick Wright, founder of History Alliance — an umbrella group that, until recently, boasted more than two dozen history groups and 1.3 million members — shut down a host of Groups Tuesday night.

The Groups closed include SF Photography (with 141,500 members), World History (104,000), Yosemite Photo (35,500), San Francisco Current Events (20,500) and California History (120,000).

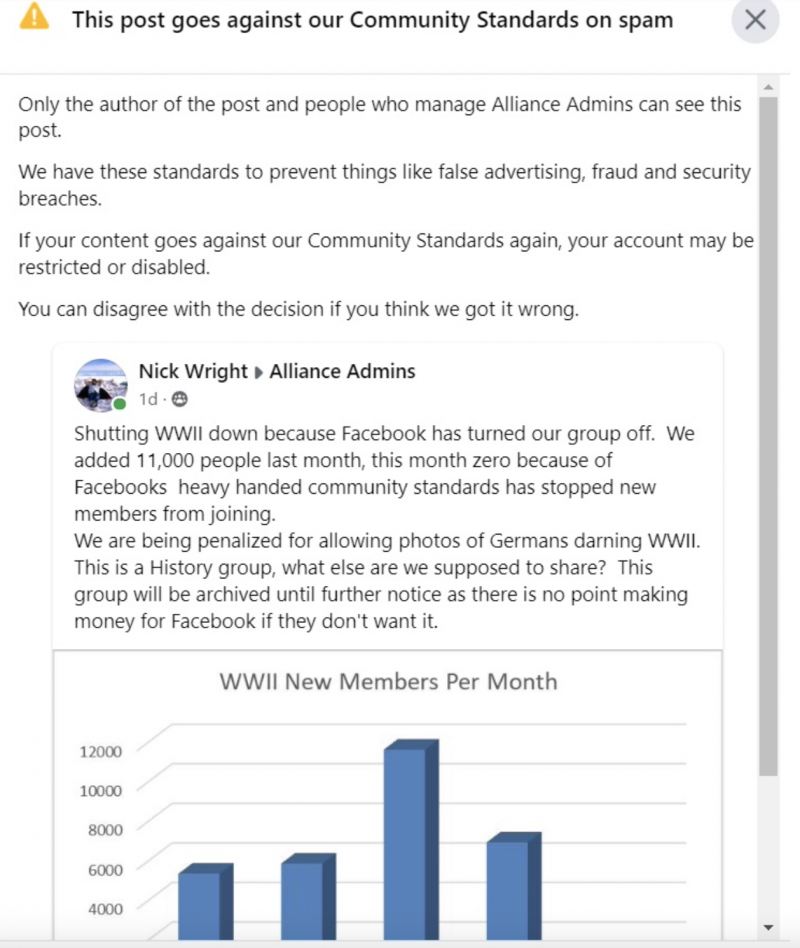

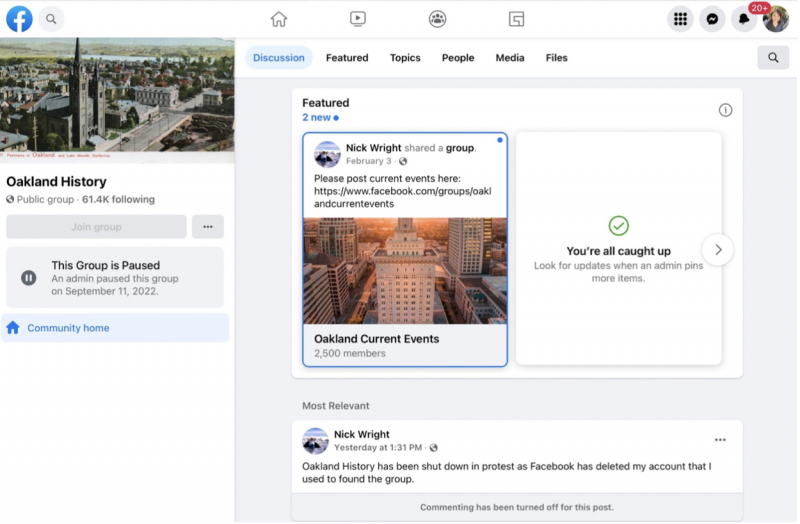

“That is a good start,” Wright wrote to KQED. Already, in mid-August, he shut down WWII (85,000 members), and then, just a few days ago, Oakland History (61,400). “I think I need to shut all these 1.3 million member groups down. There is just no end game that ends well in this.”

Wright, who lives in San José, says he and more than 30 fellow volunteer group administrators have been engaged in a war of attrition with Facebook because of the platform’s AI-led content moderation.

Facebook’s users are not really customers in the traditional sense. They don’t pay to be on the platform, which boasts close to 3 billion users. Facebook has been criticized for years for its limited human customer support, and even the power users who run Facebook Groups sometimes struggle to get help.

In a lot of ways, Facebook Groups would seem to be the best example of organic user engagement on the platform: real people talking to each other about common interests. It’s Facebook as the company wants to be seen, judging from its “More Together” ad campaign.

In this ad, young hipsters support each other in the search for mental health. But running a bunch of groups has not been good for Nick Wright’s mental health the last couple of years.

“They should be encouraging and mentoring us, not putting their foot on our necks,” Wright said. “You would think they were doing us a favor. Somehow they lost sight that we are doing them a favor.”

A failure to communicate

For example, Wright said, a photo with something flesh-colored in it can sometimes “read” as porn to the software. Or let’s say Wright, a self-taught digital stitcher of historic photographs, writes a mini-essay on a photo of San Francisco long out of copyright protection he’s unearthed. Then he posts that in SF Photography, SF History, California History and other groups in the History Alliance that seem a likely fit.

The software may well read these repeat posts as spam, and take action against his account if he keeps doing this kind of thing.

A Facebook spokesperson said this would be a “correct” determination on the part of the software, even though Wright is a). an administrator, and b). posting about history in c). history groups.

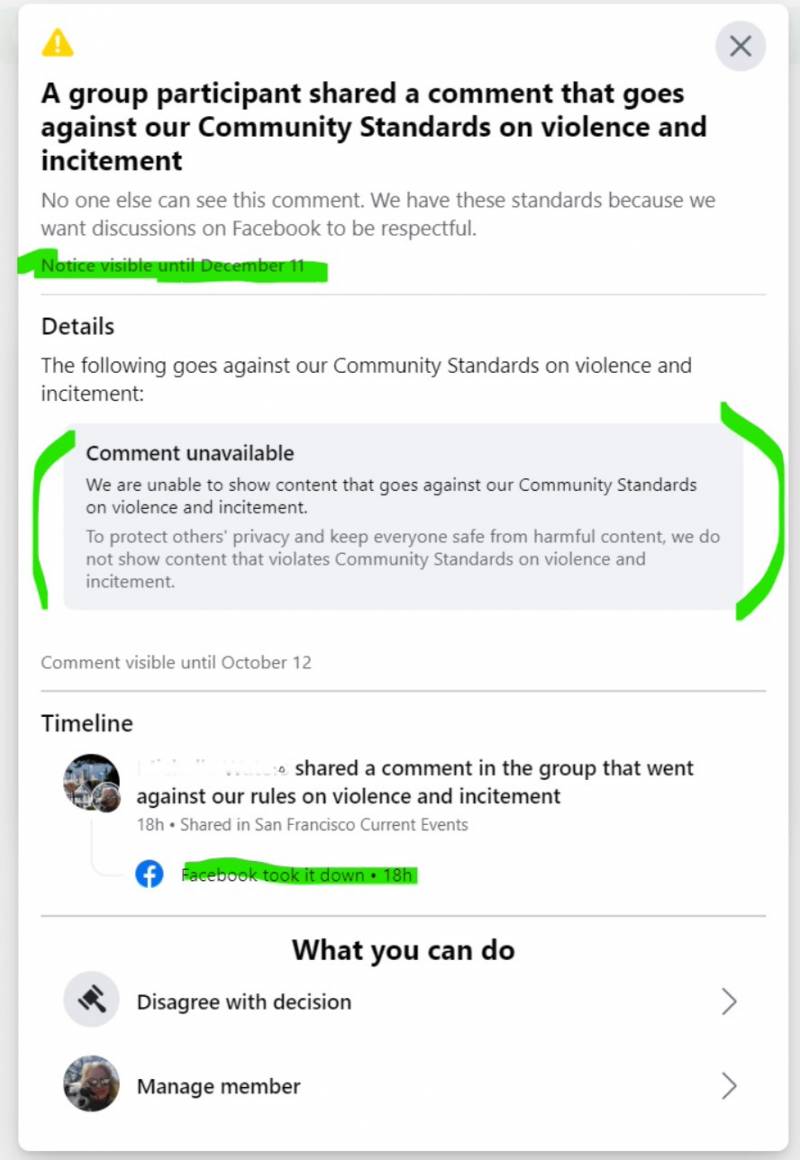

The flesh-colored photo reading as porn, though, would be an example of a “false positive,” a legitimate post the software incorrectly flags as suspicious. It happens. The rules that govern Facebook content moderation are also notoriously inconsistently applied. Wright also has a host of screenshots to back up his claims that Facebook’s software sometimes temporarily restricts moderators’ personal accounts for failing to stop false positives, or even restricts offending groups.

“We have spent tens of thousands of hours to create these groups without any pay or reward from Facebook,” Wright wrote KQED. “We are now being penalized by Facebook for running these groups, as they hold us accountable for applying their community standards to user posts and regularly victimize us with their erroneous and anemic AI, yet give us no recourse. Now they are stopping new members from joining our groups and threatening to close our groups.”

A Facebook spokesperson who dug into his claims rejects Wright’s characterization of what’s happening. The spokesperson wrote that the company recognizes there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to being a group administrator, and that Facebook has a number of resources available to help them run the groups and get help when problems arise — but, no, hands-on human tech support is not often available, even to power users like those in History Alliance.

The Facebook spokesperson also argued that the history moderators are bringing trouble on themselves in a variety of ways: using more than one personal Facebook account, a violation of Facebook terms; uploading the same posts in multiple groups at “high frequency,” which qualifies as spam; and repeatedly posting material that Facebook AI believes they don’t have the copyright to.

Here’s an example of the kind of alert Wright’s administrators receive when a post is deleted by the content-moderation software:

Hello,

We’ve removed content posted on your Facebook group San Francisco Music because we received a report that it infringes someone else’s intellectual property rights. Please ensure content posted on your group does not infringe someone else’s intellectual property rights. If additional content is posted to this group that infringes or violates someone else’s rights or otherwise violates the law, Facebook may be required to remove the group entirely.

The content was posted by ________. The responsible party who posted the content also has been notified about this report.

Thanks,

The Facebook Team

Wright started moderating in 2013, and claims Facebook used to provide a number of tools to help him manage groups that are no longer available to him. These days, for example, he uses his own Excel spreadsheet to track membership in the various groups.

All social platforms face immense pressure — from politicians, human rights advocates and, even, journalists like myself — to weed out all sorts of toxic things: porn, spam, hate speech, health-related misinformation and political disinformation. Major platforms all at least attempt to moderate content to ensure civil discourse. In some cases, laws require them to.