Newsom’s new funding proposal builds on the nearly $1 billion the state has already allocated since 2018 to address the opioid crisis, some of which has gone toward beefing up efforts to reduce trafficking. In 2022, local and state law enforcement seized 28,765 pounds of fentanyl, a nearly 600% increase over seizures in 2021, according to the governor’s office.

“Our comprehensive approach will expand enforcement efforts to crack down on transnational criminal organizations trafficking this poison into our communities — while prioritizing harm-reduction strategies to reduce overdoses and compassionately help those struggling with substance use and addiction,” Newsom said Monday in a press release.

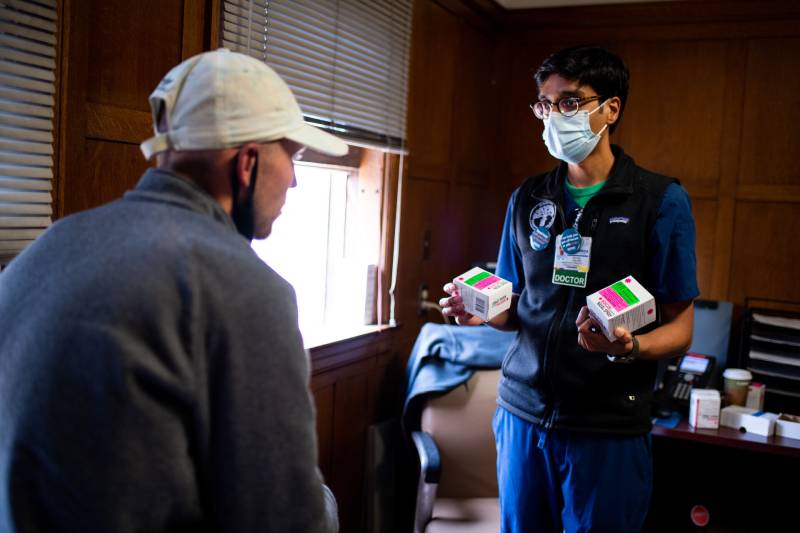

The governor also said he wants California to begin manufacturing its own supply of naloxone, which is in increasingly high demand as cities and states across the country grapple with similar upticks in overdose rates. It’s still not clear, though, how the state would produce its own drug, and how it would get around the existing patent on the popular nasal spray form of the medicine.

San Francisco public health officials were quick to applaud the governor’s proposal, saying it would “measurably increase” the city’s ability to save lives and “reduce the negative harms associated with opioid and fentanyl use.”

In the first two months of 2023, 131 people in San Francisco already have died from drug overdoses, largely driven by fentanyl, according to data from the city’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner.

“The current rate of overdoses is unacceptable,” San Francisco’s Department of Public Health said in a press release Monday, following Newsom’s announcement.

The plan, the department said, could be particularly beneficial if it yielded an increased supply of naloxone. In 2022, San Francisco distributed nearly 72,000 naloxone kits through community nonprofits, officials said.

But Laura Thomas, director of harm reduction policy for the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, criticized the governor’s new plan as “essentially a glossy repackaging of existing initiatives,” and noted there was no mention of safe-consumption sites.

“What Newsom could have done if he really cared about reducing overdoses was sign SB 57 last year,” she said, referring to legislation he vetoed that would have allowed safe-consumption sites in San Francisco, Oakland and Los Angeles. At the time, Newsom argued there wasn’t enough evidence or planning to support launching the controversial sites, where people are able to smoke or inject drugs in a clean, safe environment under medical supervision.

Thomas’ nonprofit is among a handful of organizations in San Francisco now exploring ways to privately fund and operate safe-consumption services, which remain illegal at the state and federal levels, but recently were sanctioned by the city.

To that end, Thomas also questioned why the governor’s package did not include any details about continuing to fund harm-reduction centers, like the one her organization operates, that distribute naloxone and offer other treatment services.

“What’s not in this, unfortunately, is any plan to extend the California Harm Reduction Initiative,” a $15.2 million allocation that has helped pay for staffing and other resources at privately run programs around the state, she said.

These are “the people who actually do the work of distributing test strips and naloxone to people who use drugs,” Thomas added. “That funding is now slated to end at the end of this year, and that’s where California must be investing more resources to make sure these scrappy orgs on the ground have the money they need.”