For the past eight weeks, the California Report Magazine has featured the voices of a diverse array of mixed-race Californians. Musicians, teachers, activists, parents and teenagers described the joy of belonging to multiple ethnic groups and their ability to bridge divides because of their identities. But, they also shared feelings of loneliness and isolation, of not “being enough.” Now, we hear from members of KQED’s audience about their experiences, focusing on the question: “What’s something only fellow mixed folks understand about growing up mixed?”

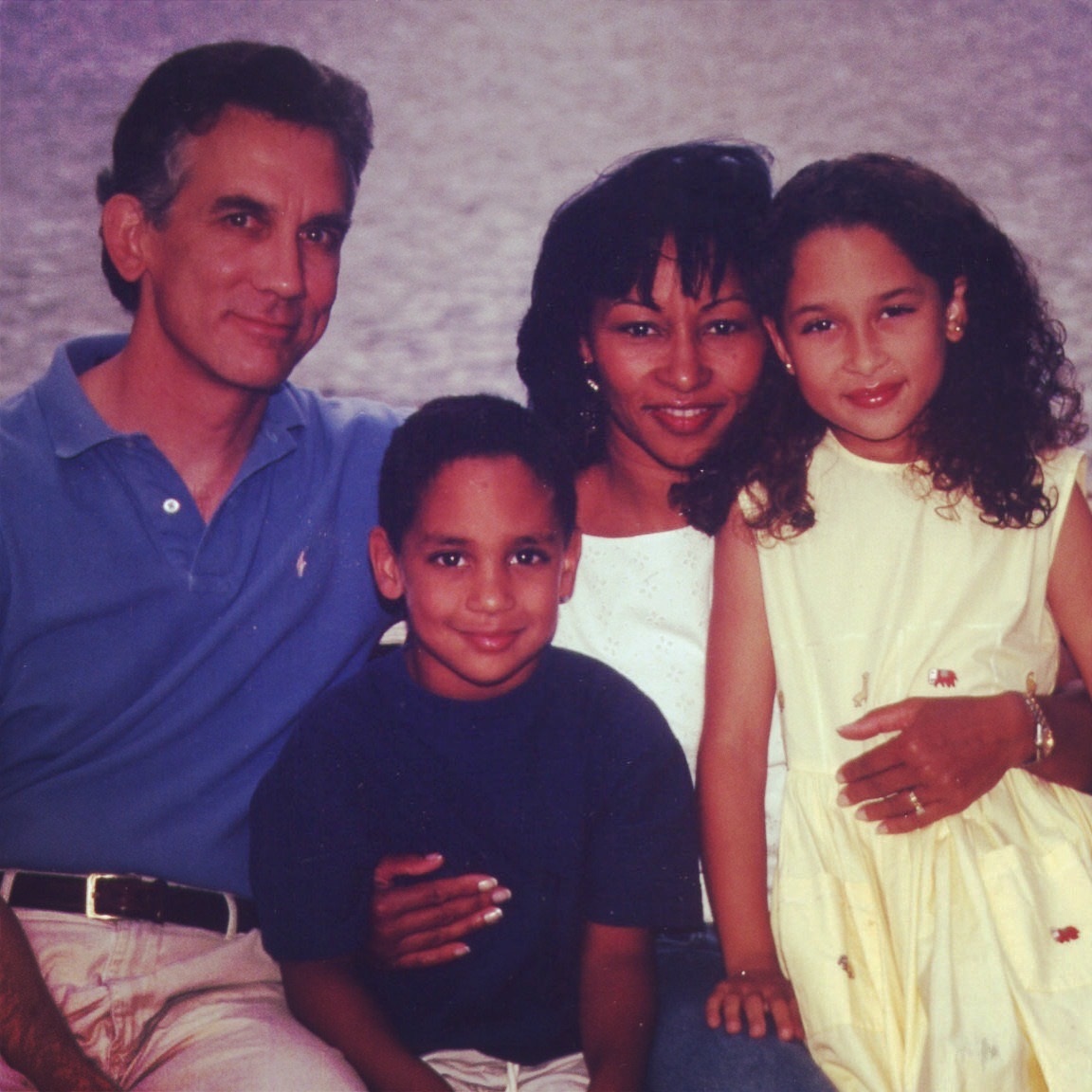

Katie Andresen, San Francisco

I tend to start my story of being multiracial with my hair. Growing up, it was the thing that defined me. In contrast to my classmates, who possessed a mostly straight assortment of blonds, browns and black, my hair sprung from the base of my head outwards and had a mind of its own. It was difficult to manage and never really sat the same way (many tears were shed as my mother combed my hair), despite the exact same methodology of styling. Multiple friends told me that they could pick me out from across the playground by recognizing my halo of curls that stood out in the sea of straight hair. Still, as I would learn later, my hair was considered the “good” type of hair — not overly kinky or coily.

It would take many years later to realize that my combination of curly hair and light skin was confounding to many. I learned how to navigate the question of “What are you?” as a lesson in geography. Most people in California hadn’t heard of the small island country my mom was from called Cabo Verde. My dad, a white Californian, had a less exciting origin story, but was still an important factor for people getting an answer to their initial question. Years later, I would realize that question wasn’t about me. It was a reflection of how race in the U.S. is constructed as a binary — you are this or that. There is no in between.

I was too white for the Black folks and too Black for the white folks. Or rather — it took too much explanation to both groups with whom I was supposed to be part of that I did, indeed, belong. It didn’t help that I routinely got mistaken as Latina. A series of conversations with both multiracial friends and strangers got me thinking; we all had similar salient experiences.

We all had answered the question “What are you?” a million times. We all had people approach us, speaking another language because they assumed we had a different racial affiliation. Outside of these one-on-one conversations, I didn’t see a place for a wider discussion of these topics. I also didn’t see a place to have an honest conversation about how structures of race and racism shaped these perceptions. I started Mixed Kid Chronicles to create that space for conversation.