If California’s proposed budget is approved as it currently stands, county offices of education will get an increase of $80 million in ongoing funding to be used toward juvenile court schools and alternative schools. It’s an amount that staff in county offices say would help them better support the students they serve and that education researchers hope will include accountability reporting for greater transparency into how county offices allocate such funding.

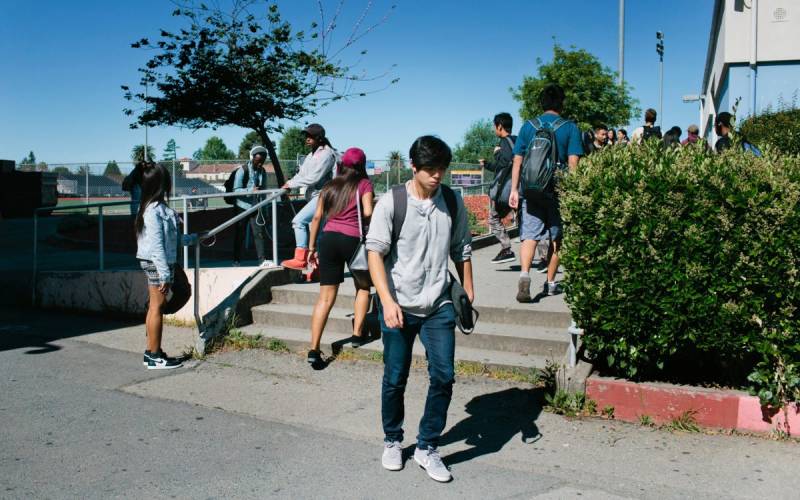

The proposed increase in Proposition 98 funds would go toward both juvenile court schools and alternative education schools run by county offices of education. Alternative schools serve those who have faced challenges in their traditional public school, including expulsion, suspension and chronic absenteeism. Some of these schools enroll students with unique needs, such as teen parents, students experiencing homelessness, and students in the foster care system.

A set of formulas outlined in Proposition 98 are used to determine the minimum funding level for education in California, year after year. One of these formulas takes students’ average daily attendance into account, which assumes that students are enrolled in a single academic institution for long periods of time. This is most often the opposite in the juvenile justice system, as the population of students they serve remain in their schools anywhere between several days to a few months.

As the state’s juvenile justice system fully shifts to being entirely county-led at the end of June, juvenile court schools will also be serving some students that were previously held in state facilities for years at a time. But for most counties, it’s far more common that the majority of their students will not be enrolled long enough to finish a single semester.