Olivia Allen-Price: That’s largely because of when San José had its biggest development boom…

Archival audio: It is now possible to have the individual styling every family wants in its home. And still have all the benefits of mass production.

Olivia Allen-Price: In the years after World War II, millions of soldiers returned home, got married, and started looking to buy property… you know, that whole American Dream thing.

Archival audio: Homebuilders anticipated the needs of newlyweds and young families. They built new suburbs that appealed to countless first time homebuyers.

Olivia Allen-Price: Up until then about two-thirds of Americans lived in cities. That’s where the jobs were. But with the availability of spacious, new homes — at least for white buyers — people left those cities.

Archival audio: At the center … an efficient kitchen … serving of meals.

Olivia Allen-Price: And all of this was made possible with another big change. The interstate highway system.

Archival audio: Most of these roads will be four, six, even eight lane expressways.

Olivia Allen-Price: These two ideas — suburbs and highways — went hand in hand. A perfect cocktail for the kind of urban sprawl we see in cities like San José.

Olivia Allen-Price: That kind of sprawl that has turned out to have some pretty big problems. First off, all that driving has not been good for climate change. Cars and trucks account for nearly half of California’s total carbon emissions. And then there’s another problem. Once all the single family lots are full, how can you house a population that’s still growing?

Olivia Allen-Price: Today, we are presenting an episode from KQED’s podcast: SOLD OUT: Rethinking Housing in America. We’ll look at how leaders in San José are trying to reimagine how residents live … and how they get around. We’ll be right back with that story.

SPONSOR MESSAGE

Olivia Allen-Price: San José was built for single family homes and cars. Housing reporter Adhiti Bandlamudi walks us through how they’re now trying to build for a denser, greener future …

Ambient sound from Berryessa BART station

Adhiti Bandlamudi: It’s a warm evening and I’m hanging at the BART train station in San José. For the past few weeks, I’ve been looking to interview someone who thinks a lot about housing and public transit. And I keep striking out. Either people are too busy or they see my big microphone and just walk the other way. But then, I spot Monika Rivera. She rides into the station, dressed all in black, on a shiny gray bike. And she doesn’t run away from me when I approach her.

Monika Rivera: Honestly, I tell people making your commute, like either biking or walking, it makes such a big difference in how you feel throughout the day.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: She’s still facing a 45 minute commute on the train, but she’s so energetic.

Monika Rivera: It makes you feel like more connected to the community, too, because you’re like biking by businesses, you like are biking by your neighbors and you just see more people. And when you’re in the car, you’re just you’re not as focused on like what’s going on around you.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: A couple days a week, Monika wakes up at 5:30, bikes from her apartment to the train station, takes the train to San José and then bikes to City Hall, where she helps manage the city’s recycling program. It sounds like a lot to me.

Monika Rivera: To me, it makes a big difference for the environment, knowing that I’m not putting all those pollutants into the air every day.

Music

Adhiti Bandlamudi: Monika and I are a lot alike. We’re both 29, recently married. We care about the environment, love being outside. And we both want to settle down in the same kind of house, in the same kind neighborhood.

Monika Rivera: I would want a home that’s in a neighborhood that’s walking distance to things like we could go to a restaurant or a coffee shop or like a grocery store, you know, and be able to be within like a ten minute walk, um ideally be close to whatever job I have.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: She and her husband have been trying to find that in the Bay Area, but homes in those kinds of neighborhoods are way out of her price range. The homes they can afford aren’t much bigger than the studio apartment they’re renting.

Monika Rivera: If we buy a home, I don’t want to go just from one tiny place to another tiny place.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: Buying a home is really important to Monika because of how she grew up.

Monika Rivera: I grew up in a small– like with my family and my sibling– like a tiny two bedroom house that they were renting.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: So she and her husband started looking for a place to buy.

Monika Rivera: I wanted to prove to myself, you know, that I could reach that.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: After months of house hunting, she found a home in Lathrop, about a 2 hour drive from San José in California’s Central Valley.

Monika Rivera: It’s three bedrooms, two baths, it has a nice backyard, has some grass, some trees and plants. We have an orange tree and a lemon tree, which is really nice.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: She said it was a relief to finally sign the papers.

Monika Rivera: It felt good. Yeah, it felt really good. I mean, I’ve been saving for years now, and, like, just all of the sacrifices that we’ve made.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: But she had to compromise – because biking to work, walking around her neighborhood– she can’t really do that in Lathrop. Nothing is within walking distance.

Monika Rivera: Even being able to go to like a coffee shop in the morning, or if you forget something at the store, you have to get in the car to go.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: When she did live in the Bay Area, she loved going to the city everyday or to the beach on the weekends.

Monika Rivera: Now it’s like to reach any of those destinations. I have to add like an hour, which is a small price to pay. You know, like you need to make sacrifices, but it’s still just something that I’m going to have to get used to.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: Another thing she’s getting used to: the heat. For the past few years, Lathrop has seen record high temperatures in the summer. Soon after they moved in, Monika got COVID.

Monika Rivera: Oh, I was sick in 100 degree heat. We, like, didn’t have blinds on our windows yet, and it was just a nightmare. I’m not used to it.

Music

Adhiti Bandlamudi: Here’s the paradox: cities like Lathrop are one of the few places in California where housing is being built– housing that’s affordable for people like Monika. But at the same time, temperatures in California’s Central Valley are soaring higher and higher each summer.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: Lathrop wasn’t Monika’s first choice. She was really hoping to find a place where she could keep riding her bike and taking the train, but with what she could afford, Lathrop felt like her only choice.

Monika Rivera: Why? Why is our society like, encouraging this or allowing it to happen?

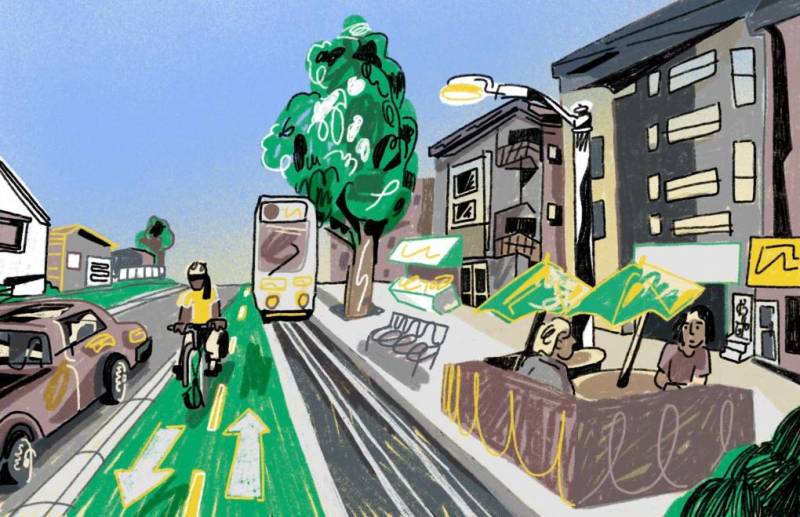

Adhiti Bandlamudi: This is an urgent problem. As the housing crisis pushes people further away from big cities, they drive more and emit more carbon. That makes climate change worse. So, instead of continuing to sprawl, why not build more homes in the city? Close to public transit and in neighborhoods where people could walk more?

Adhiti Bandlamudi: I used to live in San José, so when I heard the city was trying to make this a reality, I was really curious about it. Before I moved there from the East Coast, I had this image of a bustling metropolis. But it’s actually pretty quiet.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: A lot of people live there, but they’re all spread out. So, what would it mean if this city made good on this promise?

Music fades out. Ambient sound of Facchino district.

Erik Schoennauer: I’d love to just sort of get a lay of the land. Like what? You know what it’s going to look like one day from here.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: Erik Schoennauer points toward an old wooden fence surrounding a big vacant lot

Erik Schoennauer: And what is inside of the site right now? Just trucks and equipment.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: Erik’s technical title is land use consultant. For more than 20 years, he’s been working with developers and the city to build more housing in San José. And he wants to transform this area into a thriving urban neighborhood.

Erik Schoennauer: High density housing, high density jobs, retail, parks, mixed use neighborhoods.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: Three years ago, BART opened a train station nearby– where I met Monika. And the city figured it would be the perfect place for more housing.

Erik Schoennauer: We have to everywhere make cities that are not reliant on fossil fuels to get around.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: This is all part of San José’s larger goal to combat sprawl. More than 10 years ago, city officials noticed that too many people were getting priced out. City workers had commutes up to 2 hours long. So they came up with a plan to build 60 urban villages across San José.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: State Assembly Member Ash Kalra represents the city and was one of the loudest advocates for the plan. Here he is selling the idea in a promotional video.

Sam Liccardo: Urban villages have a lot of benefits. First of all, by bringing people together, both in terms of their housing and their jobs and the stores and restaurants they go to, you’re being much more efficient with your use of land.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: Imagine tall apartment buildings with shops on the bottom and a train line running through the middle. A pedestrian’s paradise.

Music

Adhiti Bandlamudi: This new housing would be a big change for San José. It’s the 12th largest city in the country, but it feels like a giant suburb– all the homes are spread out.And that’s because of its history.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: Between the 1950s and 1970s, highway expansion set the tone for city planning. Sam Assefa runs California’s Office for Planning and Research — that’s basically the state’s own think tank to solve its toughest problems, like sprawl.

Sam Assefa: Sprawl was literally on steroids with single family developments quickly gobbling up farmland, open space and spreading out.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: In the early 1900s, San José was a small city of only 17 square miles. Today it’s 181 square miles. And most of it is dominated by single family homes — a house that’s home to only one family.

Sam Assefa: This is the American dream. And we know that single family homes generally perpetuate sprawl.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: More than 90% of San José’s land is zoned for single family homes. For decades, it was illegal to build other kinds of housing — like apartments and duplexes — in most of the city. That history created a lot of housing inequity.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: Starting in the early 1950s, white families were moving into San José from bigger cities like San Francisco and Oakland. Fair housing laws hadn’t been passed yet, so a lot of the new homes were off limits to practically anyone who wasn’t white. Scars from that history are still visible today. Black and Latinx residents of San José are far less likely to own their homes than white and Asian residents. San José wants to right some of those wrongs. And the urban villages could help. They are supposed to include some affordable housing, bring more jobs and give more people the opportunity to live here.

Sound of walking around Berryessa Urban Village

Adhiti Bandlamudi: But this whole urban village dream is really slow going. It’s been more than 10 years since San José officials said they wanted urban villages all over the city. So far, only a handful have been built. There’s already part of an urban village next to the BART Station. There’s a tall apartment building with hundreds of units. But walking around that area…

Adhiti Bandlamudi (in the field): So I just had to cross a one, two, three, four, five, six lane road to get to the other side.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: It’s just not that easy. This is one obstacle San José is up against. It’s trying to build a pedestrian-friendly neighborhood in a place planned around cars. Sidewalks run alongside the apartment building, but it’s just not very welcoming to walk next to a busy road. There is a Safeway and a Dunkin Donuts, but you have to cross a huge parking lot and another four-lane road to get there.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: The apartment building was built with shop and restaurant space on the ground floor, to make it more convenient and interesting to live here — but it’s mostly vacant. That’s partly because demand is down post pandemic.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: There’s barely anyone walking around. I finally run into Juan Carlos Navarro. He lives in a townhome a few blocks away and is out with his dogs. I’m so excited to see someone, I’m fumbling over myself.

Adhiti Bandlamudi, in the field interviewing Carlos Navarro: How do you feel about all of this new development coming and the…

Carlos Navarro: And let me call you back, okay? (hangs up phone) Oh, sorry.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: He says this area used to be a bit of a ghost town, but that’s starting to change.

Carlos Navarro: We definitely like it because it’s uh– we feel better. We feel secure now walking along the block because this was all empty before. And it wasn’t– it wasn’t as good as it is now. So we definitely like it.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: He hopes it becomes more lively as more housing gets built and more shops get filled.

Carlos Navarro: I hope to see more people, more, you know, entertainment areas, stores and [00:10:40] I would hope to see that.

Music

Adhiti Bandlamudi: As San José tries to make good on its urban village promise, it’s kinda handcuffed by some of its own policies. And you can see it in the plans for Erik Schoennauer’s development. He has a vision for tall apartment buildings, but what’s the first thing he’s going to build?

Erik Schoennauer: Single family and townhomes.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: Yeah. The first thing Erik is going to build is more standalone houses. That’s because the neighborhood around the empty lot is already full of single family homes. And city policy doesn’t allow tall buildings to be built right next to them. Because it might cast a shadow. So Erik has to build a buffer.

Erik Schoennauer: Put a row of lower density housing units up against the existing single family and put the taller buildings more internal on the site.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: Cities across California have laws like these which protect single family homes and prevent denser housing like apartments and condos from being built nearby.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: What’s more, apartment buildings are riskier because developers have to build the whole thing before they can rent or sell any of the units.

Erik Schoennauer: Whereas single family and townhomes, you can build and sell as you go.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: Even though the city wants to see more dense development, they’re not the ones building it — it’s up to developers. And it has to make sense to their bottom line. Right now, it doesn’t. Interest rates and construction costs have soared and there’s less demand for office and retail space. Erik hopes another developer will eventually build the apartments — but he’s uncertain as to when that might happen.

Erik Schoennauer: I believe it’s an inevitable evolution to move towards denser, more mixed use development. It’s all evolving in the right direction, but it takes time.

Fade Music Out Here

Adhiti Bandlamudi: Evolution takes a long time.

Kelly Snider: It’s just waiting. I mean, everyone’s waiting. There’s no- it’s not happening.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: Kelly Snider has been living in San José since 1999. She teaches Real Estate Development at San Jose State and is really frustrated with the city’s progress with their urban village plan.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: She thinks there’s a different way to get more housing built.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: I meet her in a quiet neighborhood filled with small bungalows, each with their own front lawn.

Kelly Snider: So, where are we? Where are we right now? We are in downtown San José, outskirts of downtown San José.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: It’s a little brown house with bright blue accents around the windows. It’s got three bedrooms, two bathrooms and a big backyard. At the end of the block, there’s a train station where you can catch a ride to downtown San José.

Kelly Snider: We have a fantastic public elementary school on this corner.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: This house is Kelly’s pilot project. She bought it from Raul Lozano, a local activist who wanted to see more housing built here. He wanted to split his home into two separate units, but was struggling with the process. And at the same time, Kelly, who is an experienced developer, wanted to help.

Kelly Snider: This front unit is a one bedroom, so it’s got a living room and a nice kitchen, a full bathroom, and then a nice bedroom. And we charge $1500 a month for this. And that includes utilities.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: $1,500 for all that is a steal in the Bay Area. And Kelly didn’t stop there. She also built a small two bedroom house in the backyard, where Raul lived until he passed away in February. It’s now home to two of Raul’s friends who were dealing with housing insecurity.

Kelly Snider: They would often, you know, spend time with family in the valley and then sleep in their cars one or two nights a week here. We approached the mother and said, Would you like to move into this house? And she said, yes. And she and her son live here now.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: That small house is technically called an ADU, or an accessory dwelling unit. You might know it as a granny flat or a casita. And it’s the hottest thing in California housing.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: Recent state and local laws have made them easier to build. There are even grant programs that will cover some of the costs. And San José has really embraced them. Last year, the city issued over 500 permits to build new ADUs. There’s still some space on Kelly’s lot. And she wants to build a duplex there — so even more homes on a plot of land that used to just have one. Kelly knows there are skeptics.

Kelly Snider: One of the reasons why I wanted to do this is because every time I bring someone here they’re like, Well, that’s just a tiny little lot. You can’t fit a whole new house on there. And I’m like, Oh, I can fit a whole house on there.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: Even if she can build it, not everyone wants it. Many of the people who moved to San José came for the backyard and the quiet neighborhood with tree-lined streets. But Kelly wants to show people, you can still have that and add more housing. After buying Raul’s place, she formed a company to help more people split their homes.

Kelly Snider: Everyone who comes to see it says, Oh, I didn’t know it would look this nice. I didn’t know you could fit all of this.

Music

Adhiti Bandlamudi: And for what it’s worth, it doesn’t feel crowded. This is still a quiet street and there isn’t a tall building in sight. Kelly thinks San José is moving in the right direction with ADUs and just needs to keep making it cheaper and easier to build them.

Kelly Snider: They know the knob to switch and they’ve already started twisting it. They just need to twist it further.

Music

Adhiti Bandlamudi: I know I’ve been picking on San José, but the thing is, it’s like a lot of cities in California. They were all built on an idea that sounded great at the time — a spacious home with a yard of your own. A car that could take you anywhere. But that idea has led California into its housing and climate crisis.

Adhiti Bandlamudi: So, maybe it’s time to embrace some new ideas for how our cities are built and how we’ll create a sustainable future. It might mean living closer to each other, driving less, walking more. And, if you ask me, that actually sounds pretty great.

Olivia Allen-Price: That was KQED housing reporter Adhiti Bandlamudi. This story is from the KQED podcast: SOLD OUT, Rethinking Housing in America. Their latest season explores the intersection of climate and the housing crisis. Another episode you might enjoy is called “Electric Avenue” and it follows a group of neighbors in Oakland who are working together to make their homes more efficient and climate resilient. Find Sold Out wherever you listen.

Olivia Allen-Price: This story was edited by Erika Kelly and Kevin Stark. Sold Out is hosted by Erin Baldassari. Jen Chien was a contributing editor. Sound engineering by Brendan Willard. Cedric Wilson wrote the Sold Out theme song. Thanks also to Katie Sprenger, Cesar Saldaña, Maha Sanad, Ethan Toven-Lindsey, Holly Kernan, Otis Taylor Jr., Molly Solomon, Amanda Font, Christopher Beale and the whole KQED Family.

Olivia Allen-Price: I’m Olivia Allen-Price. Bay Curious is going to be dark next week for the Thanksgiving holiday, so I’ll say this now… We are so thankful that you listen to our show … it is truly an honor and privilege. And we hope you have a joy-filled week, whatever that looks like to you.

Have a good one.