Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

[Outside sounds of wind]

Olivia Allen-Price (at scene): Hey everyone, Olivia Allen-Price here. It’s a cold, but sunny Thursday afternoon, and Bay Curious producer Katrina Schwartz…

Katrina Schwartz (at scene): Hello, that’s me!

Olivia Allen-Price (at scene): …And I are knocking around The Presidio.

Katrina Schwartz (at scene): That’s the roughly 2 square mile park at the northwest tip of San Francisco.

Olivia Allen-Price (at scene): So far we’ve seen the little yoda statue surrounded by the fountain.

[Kid yelling “Yoda!”]

Olivia Allen-Price (at scene): What do you think of yoda?

Katrina Schwartz (at scene): It looks a lot like yoda. I wish I could rub his belly, but he’s too high up there.

Olivia Allen-Price (at scene): The dramatic cliff side vistas overlooking the Golden Gate Bridge.

Katrina Schwartz (at scene): Wow!

Olivia Allen-Price (at scene): We’ve got it all! We’ve got the Golden Gate Bridge. We have the Marin headlands. We have Point Bonita Lighthouse.

Katrina Schwartz (at scene): Beautiful.

Olivia Allen-Price (at scene): Now we’re a short walk from the bluffs, just over Lincoln Ave. And there are dozens of old military buildings. Beige exteriors, pretty large buildings, red roofs and we’re standing in the middle of a big field.

Katrina Schwartz (at scene): And what’s odd is there are very few people around. It’s a little bit eerie.

Olivia Allen-Price (at scene): Compared to where we were earlier, where all the buildings had been kind of fixed up, they were being used as businesses, these are empty.

Katrina Schwartz (at scene): This is the heart of Fort Scott, what once was part of the largest army post on the Pacific coast.

Olivia Allen-Price (at scene): Over the years listeners have sent in a handful of questions about this place, and today we’re answering a few of them…

Katrina Schwartz (at scene): Like what exactly is Fort Scott?

Olivia Allen-Price (at scene): What was life like here for soldiers?

Katrina Schwartz (at scene): And why do these buildings remain closed up, when so many others in the Presidio have been put to modern use?

Olivia Allen-Price (at scene): That’s all just ahead on Bay Curious. Stay with us.

Olivia Allen-Price: Fort Scott parade grounds is an often overlooked piece of the Presidio, despite being steps away from Golden Gate Bridge. KQED’s Bianca Taylor takes us there to answer some of your questions.

Bianca Taylor: One of the first things to know about Fort Scott is that its official name is Fort Winfield Scott.

Rob Thomson: Winfield Scott was one of the most prominent U.S. Army officers of the 19th century. And he was the person that the Army named many, many things after all over the country, including this place.

Bianca Taylor: That’s Rob Thomson.

Rob Thomson: I’m the Federal Preservation Officer for the Presidio Trust.

Bianca Taylor: The Presidio Trust is an independent federal agency which manages the majority of the buildings in the Presidio, including Fort Scott. Rob is giving me a tour, starting with the large grassy lawn that’s shaped like a horseshoe — called the parade ground.

Rob Thomson: We’re surrounded by ten enlisted men’s barracks buildings, most of which are vacant right now. There’s also a spectacular view of the Golden Gate Bridge, which nobody knew was going to be there when all of these buildings were built.

Bianca Taylor: There are about 100 buildings that make up Fort Scott, including a gym, officers’ clubs, and even a notorious jail — but we’ll get to that in a little bit.

Today the site is mostly vacant — its buildings boarded up against the elements. But more than a century ago, Fort Scott was busy as the headquarters for the Army’s coastal defenses in the Bay Area.

[Music begins]

The military history of the Presidio dates back to the Spanish colonization of Ohlone land in the 1700s. With its isolated cliffs and expansive views of the Bay, this part of San Francisco was a strategic location for protecting California against attackers from the West. After the U.S. gained control of it in 1848, the Presidio became the largest Army post on the Pacific Coast.

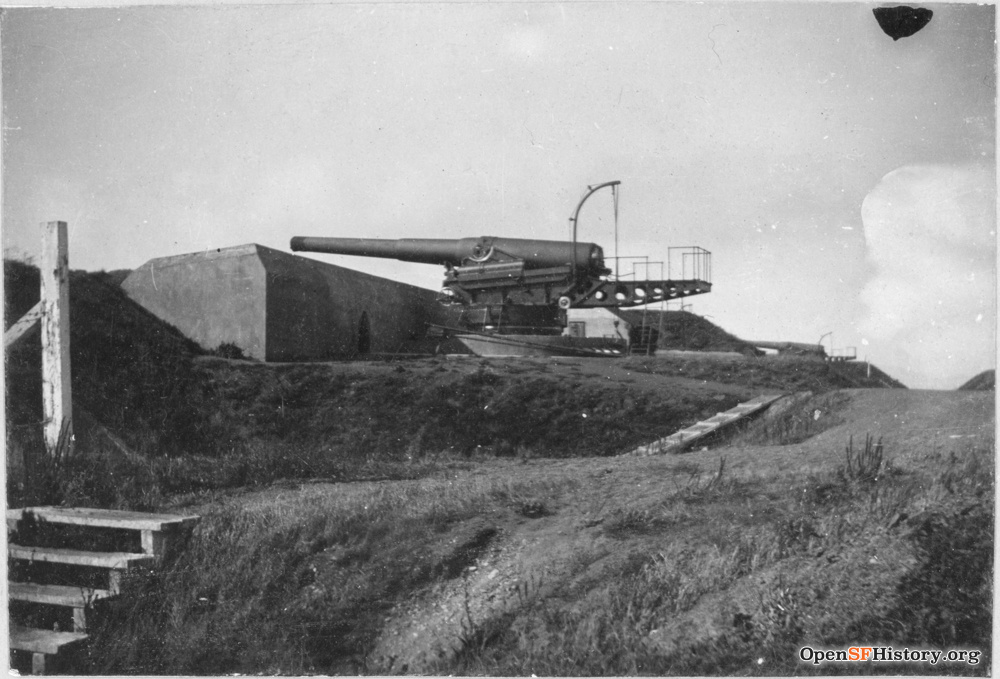

Fort Scott was built several decades later in 1912. As many as 1200 enlisted men lived and worked here. Their main duty was operating the 17 artillery batteries that lined the coast, basically giant cannons that shot bombs into the sea to protect the Pacific coast from attacking ships. You may have even seen the remnants of these batteries on a hike.

Rob Thomson: They’re these mysterious concrete structures that are out on the coastline that pepper our beaches and the surrounding bay. Those were state of the art defensive installations that were constructed beginning in the 1890s.

Bianca Taylor: Manning these batteries was a tough job. They had to be looked after around the clock, which meant men were marching three miles round trip to camp out on some of the coldest, windiest, and most exposed parts of the coast.

[Sound effects: “Sandby… fire”]

Rob Thomson: The soldiers who had to be out there all the time and this is pretty well documented, didn’t have a great day to day life.

Bianca Taylor: Practice fire was conducted a few times a year, weather depending. Anyone who’s tried to plan a beach day on the Coast can relate to this article in the San Francisco Examiner from September 30, 1915:

[Sounds of wind and a foghorn]

Voice over actor: Foggy weather yesterday once more interfered with the artillery target practice at Fort Winfield Scott, and the mortar and 5-inch gun practice was put over until 10 o’clock this morning.

Bianca Taylor: It didn’t take many years though for advancements in warfare to render the coastal batteries at Fort Scott obsolete.

[ Sound of a plane flying overhead]

By World War Two, the advent of air power meant the real threat to San Francisco was coming from airplanes, not ships. In 1950, the Army terminated its Coast Artillery Division and the attention of Fort Scott turned to mapmaking, surveying, and anti-aircraft defenses.

Rob Thomson: There is a Nike missile site here in the Presidio, along with perhaps a better known one over in the Marin headlands. And that was really the focus of defensive activity here, rather than coast artillery batteries any longer.

Bianca Taylor: Nike missiles, which look like high tech cousins of the coastal artillery batteries, were designed to shoot planes out of the sky. And they dominated the military landscape during the Cold War.

If you want to get a snapshot of what daily life looked like at Fort Scott, you don’t need to look any further than the attic of building 1216.

[Sound of climbing stairs. “Oh my goodness!”]

Rob Thomson: This is an area that we currently keep off limits even to the staff who work in this building, because we’re trying to preserve the murals that are painted on the walls here.

[Wow]

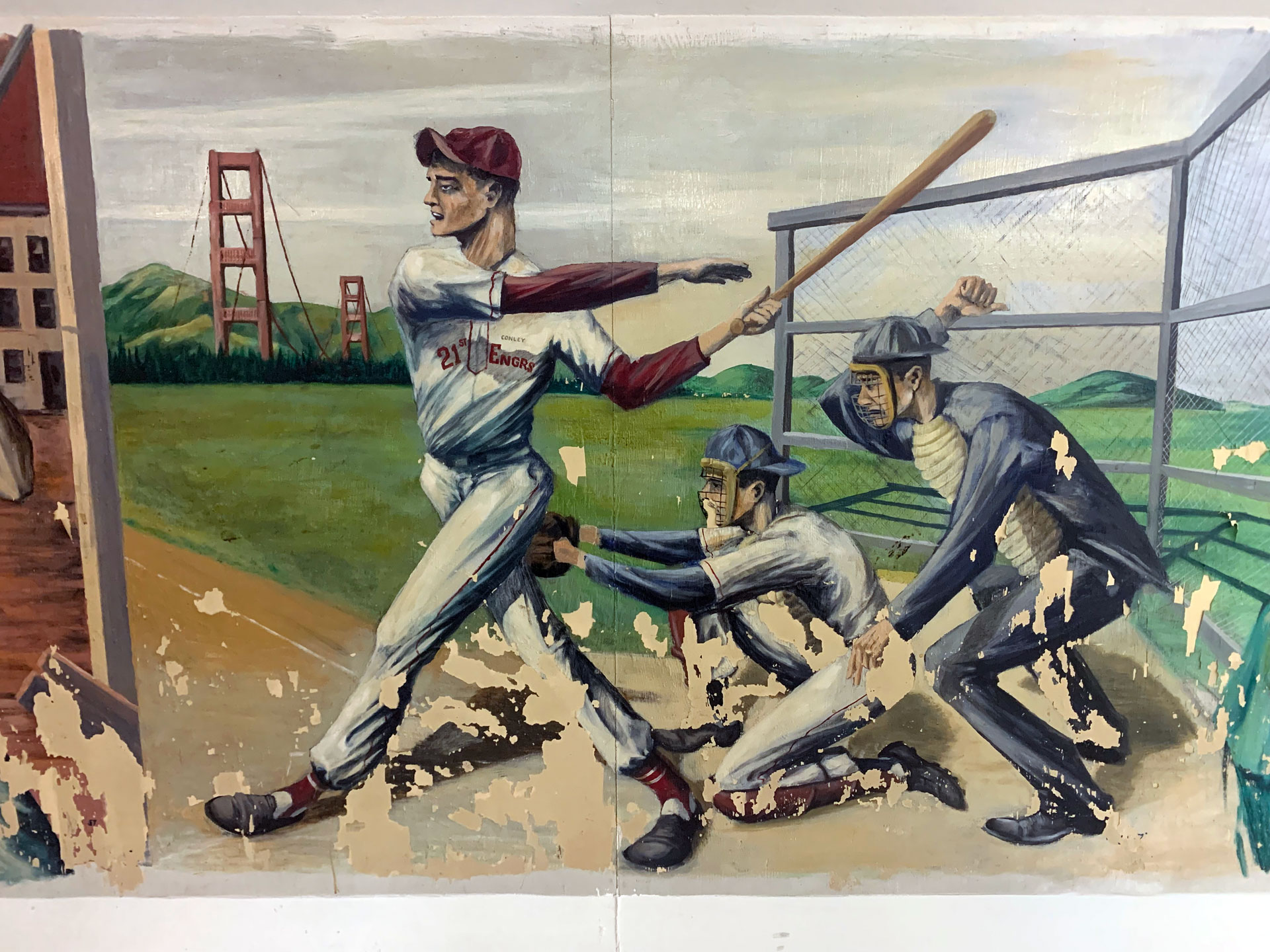

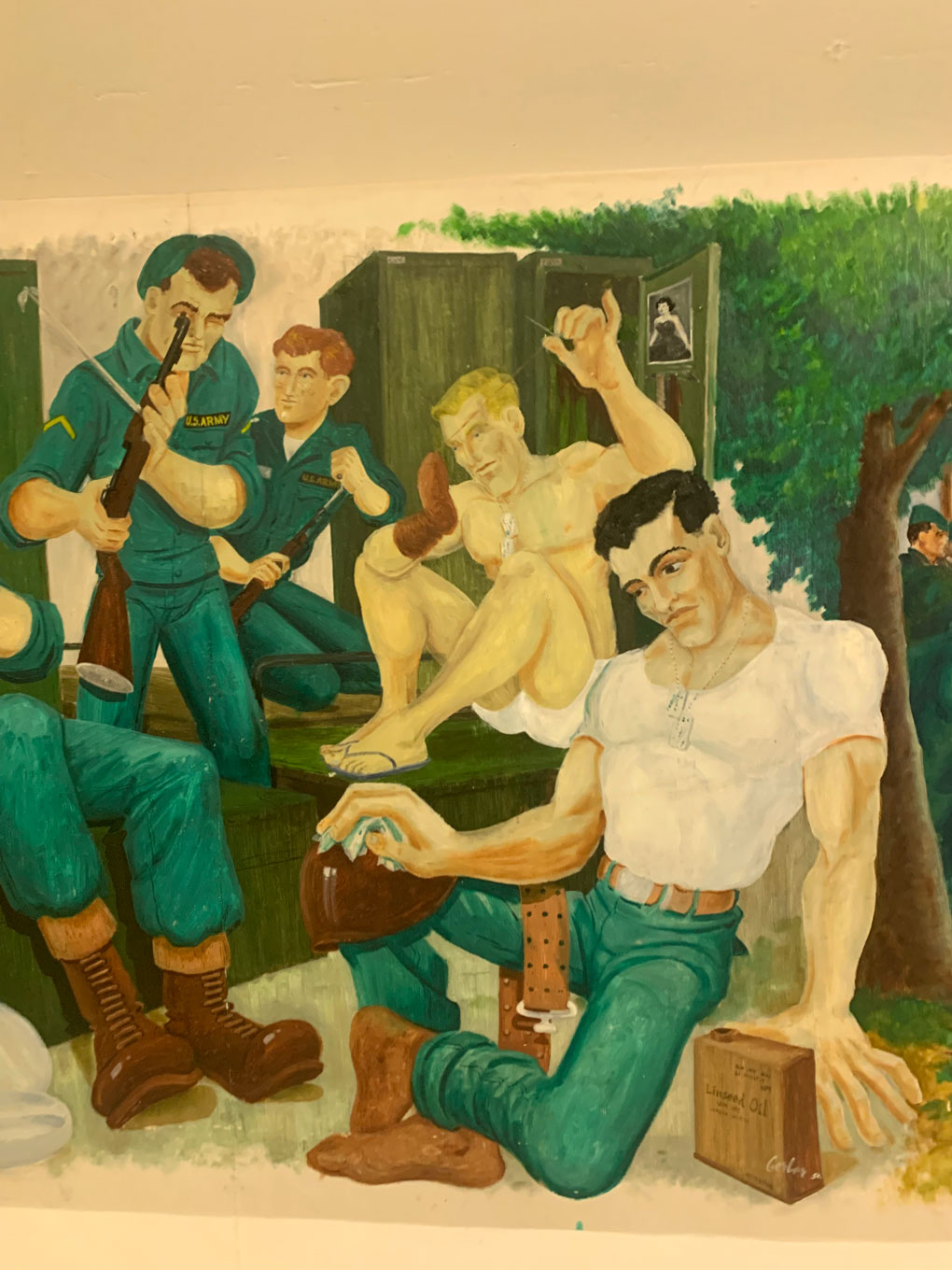

Bianca Taylor: In this attic-turned-classroom space, the long white walls are covered in painted murals that wrap around the room. The paintings depict everything from soldiers playing baseball on the parade field, to a gas mask training for chemical warfare.

Rob Thomson: The story goes that a couple of the soldiers who had been drafted during the 1950s weren’t so happy about having wound up in Army life. But they did have a background in fine arts, and so their commanding officer invited them to spruce up the classroom with the murals that you now see around us.

Bianca Taylor: The main artist was a man named Perrin Gerber, who was a specialist third class at Fort Scott. He painted the murals in 1956 and 57. Rob says Gerber’s family has come to see the murals for themselves and pointed out personal touches.

Rob Thomson: This image that’s painted on the inside of a locker on one of the murals is supposedly his girlfriend and future wife.

Bianca Taylor: But building 1216 isn’t the only structure at Fort Scott with a story to tell.

Bianca Taylor (in scene): Is this the jail? Stockade?

Rob Thomson: This is the Fort Scott Stockade also known as a jail, building 1213 It was built in 1912. This was the site of the famous Presidio Mutiny.

Bianca Taylor: In 1968, the United States was locked in the midst of the Vietnam War. Protests were happening all over the country.

Archival tape: Because I am sick of the racist war in Vietnam when we don’t have justice in the United States.

Bianca Taylor: American soldiers were also protesting, including in the Presidio. The Fort Scott stockade was overcrowded with military personnel who had voiced anti-war sentiments and as conditions inside the jail got worse, tensions between guards and soldiers escalated.

The situation came to an explosive head on October 11, 1968 when military police at Fort Scott killed a 19-year old prisoner named Richard Bunch.

In the 2005 documentary, “Sir, No Sir” director David Zeiger interviewed some of the men who were there that day.

“Sir, No Sir” Footage: The guard shot him and killed him, you know, point blank. And his only crime is, not wanted to be there and, um, going AWOL. So we reacted, uh, viscerally and with anger and disgust and outrage. We tore that jail apart. Uh, we ripped the wires out of the walls, ripped the squawk box off the wall.

Bianca Taylor: After their initial anger, the soldiers got organized and decided to take a stand.

“Sir, No Sir” Footage: We came to a decision that the best thing we could do was to have some kind of a demonstration. And it was at the roll call formation. We had a signal, and that was when we were supposed to break ranks. And we did. And then we walked over here and sat down.

Bianca Taylor: 27 prisoners staged a sit-in protest at the stockade. They sang “We Shall Overcome” and read a list of demands.

“Sir, No Sir” Footage: At a certain point, the commandant came out and read us, uh, the Mutiny Act, and we just kept singing louder and kind of linked arms and sing and sing.

Bianca Taylor: The 27 protestors were all charged with mutiny, a crime punishable by death.

“Sir, No Sir” Footage: And we were scared, man. I’ll tell you, we were really scared.

Bianca Taylor: Their actions drew support from around the nation, and the mutiny charges were eventually dropped.

“Sir, No Sir” Footage: They were finally listening to us, man. That’s the first time I can ever remember anybody listening to us while I was in the military.

Bianca Taylor: The impact of their protest went beyond the gates of Fort Scott.

Rob Thomson: And it sparked a movement of protest within the U.S. military against the Vietnam War, which was a really important moment in that chapter of our history.

Bianca Taylor: You can still see ghosts of the Presidio Mutiny today. If you look hard at the wall of one of the solitary confinement cells, you can read the words “Bunch was murdered” etched into the wall.

Congress voted to end military operations at Fort Scott, and the entire Presidio, in 1988. Six years later, the region became a part of the National Park Service, which along with the Presidio Trust, still manages the site today.

For nearly a century, Fort Scott had a perfect record of keeping San Francisco safe from attacks from the sky and the sea because there were none.

Rob Thomson: And so a lot of people will debate, well, was there no attack because it was so well-defended or were they never needed because we were never attacked? And that’s up for, you know, historians to debate.

Bianca Taylor: Standing on the Fort Scott Parade grounds now it’s so peaceful, with chirping birds and the Golden Gate bridge peeking out between the rooftops, that its tumultuous military past feels like a very long time ago. But as Rob points out, the military is largely responsible for a lot of what the Bay Area looks like now:

Rob Thomson: When Army bases closed, they’ve in the Bay Area traditionally been handed over to public open space agencies. So if it weren’t for the military, we wouldn’t really have the same outdoor access and traditions that we have in the Bay Area.

Bianca Taylor: Other state parks that used to belong to the military include Estuary Park in Alameda and Fort Ord Dunes State Park in Monterey.

As for plans to restore Fort Scott’s buildings for public use, that’s a long way off. Right now the empty buildings have been what Rob describes as “mothballed.”

Rob Thomson: So we’ve invested a certain amount of money to make sure that the roofs are secure, that we’ve painted them, that the windows are watertight, and that they’re sitting here in a state that is somewhat arrested deterioration.

Bianca Taylor: The Presidio Trust held a competition in 2018, inviting organizations to submit their ideas of how they would revitalize Fort Scott. WeWork and OpenAI submitted a joint proposal, but the Trust rejected it. They said the companies didn’t share their humanitarian vision for the abandoned 30 acres and the competition didn’t go anywhere. Rob says even though the Trust has been focusing on other priorities in the 1500 acre Presidio…

Rob Thomson: We haven’t turned our backs on Fort Scott by any means. We’re still taking good care of it, making sure it’s in good working order so that when we do have the resources and we have taken care of some other priorities, namely our infrastructure, we can come back here and rehab these buildings.

Bianca Taylor: There are two residential neighborhoods in Fort Scott where people are currently living. These 1500 residential units are former apartments and homes of Army officers that were stationed here. This opens up the question of converting some of the other buildings into housing in the future.

Rob Thomson: You know, it’s possible that some of these barracks buildings could be converted into residential, but we haven’t gotten to that part in the planning yet.

Bianca Taylor: It may be some time before you can wander around the inside of Fort Scott, but it’s still a lovely place to visit, maybe have a picnic, or just walk through a little piece of Bay Area history.

[Outro music]

Olivia Allen-Price: That was KQED’s Bianca Taylor.

If you love Bay Curious one small step you can take is subscribe or follow the show in your podcast listening app. It’s free, and is the best way to make sure you don’t miss an episode. Thanks!

Bay Curious is made in San Francisco at member-supported KQED. Our show is produced by Katrina Schwartz, Christopher Beale and me, Olivia Allen-Price. Additional support from Jen Chien, Katie Sprenger, Cesar Saldana, Maha Sanad, Holly Kernan and the whole KQED Family.