Episode Transcript

Olivia Allen-Price: One of the best parts about a deep and long-running friendship is you can poke a little fun at each other for your quirks. Like how you’re a diehard fan for a chronically losing sports team or how you put ketchup on everything – gross. For Nate Puckett, his friends rib him about how he never leaves the city of Alameda.

Nate Puckett: So I work here, I live here, my kids go to school here. I have a 4-year-old and a 6-year-old. So I don’t leave the island for like weeks. And people make fun of me for that.

Olivia Allen-Price: Alameda is an island, in case you didn’t know, and that fact is pretty wrapped up in the identity of some people who live there.

Nate Puckett: I have a T-shirt that says Islander. That’s, like, Alameda themed. There’s Alameda Island Brewing. Like, you talk about whether, you know, you’re on the island or not on the island.

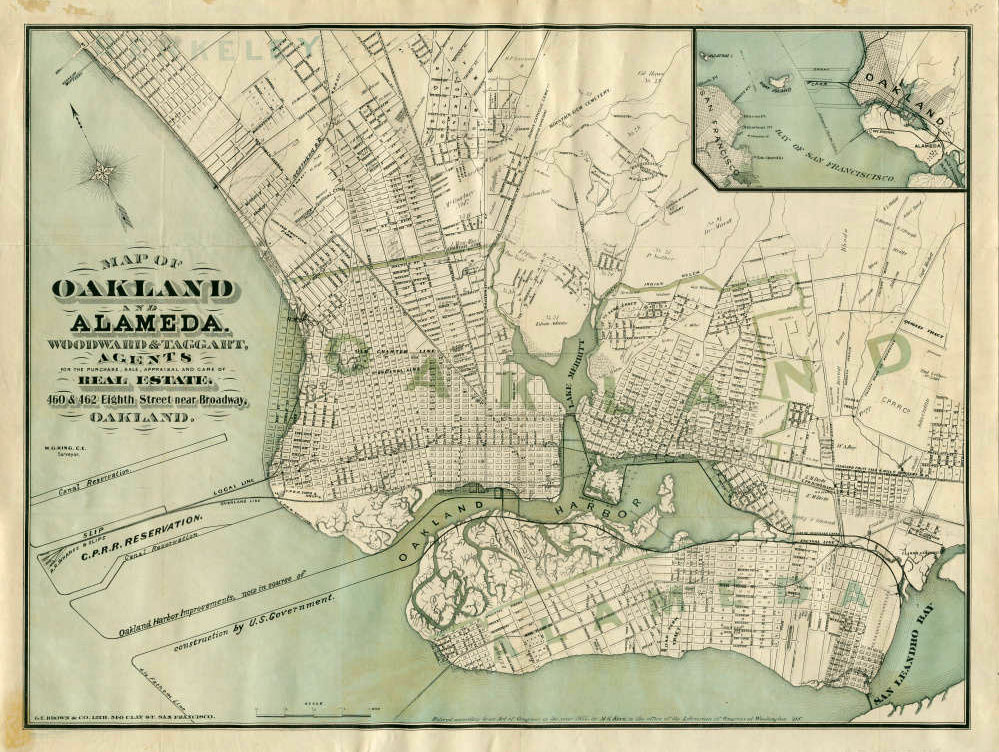

Olivia Allen-Price: But recently, Nate’s sense of place was thrown off-kilter. He was eating ice cream at a local spot – Tuckers. He glanced up at a historical map hanging on the wall. And there, he saw something that shook him to the core. Alameda was connected to what is now mainland Oakland.

Nate Puckett: It kind of felt like we’ve been all living a lie. It kind of felt like, no, that’s wrong. Alameda is an island.

Olivia Allen-Price: But no. The map was not wrong. It was just old. Alameda is not a natural island. And it almost never became an island at all.

Bay Curious theme music starts

Olivia Allen-Price: On this episode of Bay Curious, we’re going to find out how and why Alameda was sliced off the mainland. It’s a story with enough twists and turns to make your head spin. I’m Olivia Allen Price. We’ll dive in just after this.

Sponsor break

Olivia Allen-Price: Making Alameda into an island took nearly 30 years. And in the end, the original idea for the massive excavation, didn’t quite pan out as planned. KQED Producer Pauline Bartolone tells us all about the bumpy journey.

Pauline Bartolone: Flooding, legal battles, an economic slump and raw sewage. They’re all part of Alameda’s island origin story.

Music starts

It all starts back in the 1870s, Alameda was a big peninsula, jutting out like an outstretched arm from what is now Oakland’s Fruitvale neighborhood.

Back then, things were pretty quiet where Alameda connected with the mainland. Not many people lived in this marshy region. Think open fields and maybe just a few estates of wealthy families.

Just to the west was a waterway, the Oakland harbor, that opened up to the San Francisco Bay. And it was becoming a bustling center for maritime commerce. More and more ships were arriving since the Gold Rush, bringing all sorts of goods. But navigation in this waterway was tricky. Sediment on its floor would shift — a lot! — causing all sorts of problems for boats.

Music ends. We hear the sounds of street traffic and outside noises.

Dennis Evanosky: The trouble is, there were sandbars. And there were all kinds of impediments.

Pauline Bartolone: Alameda historian Dennis Evanosky took me and our question-asker, Nate Puckett, on a tour along Alameda’s waterfront. He says around what is now the Port of Oakland, the waterway was wild and untouched, with sandbars that would ebb and flow with the tide.

Dennis Evanosky: They were there on Monday, Wednesday and Friday, then they’d be over here on Tuesday and Thursday, this place else.

Nate Puckett: Oh, yeah, haha.

Dennis Evanosky: And it impeded the shipping traffic!

Pauline Bartolone: The unpredictable nature of the waterway didn’t work for the shipping industry, which wanted to get more boats into the port. Oakland had big development ambitions, says Richard Walker, a professor emeritus in geography at UC Berkeley.

Richard Walker: Then, the sense of competition with San Francisco is intense, even though there’s a lot of San Francisco investment in Oakland. But you start to create Oakland having its own capitalist class, its own leadership who have banks in Oakland, have businesses, you know, have shipping companies, and they actually have a local interest. And that grows and grows so that Oakland, you know, by the early 20th century, is really thumbing its nose at San Francisco.

Pauline Bartolone: Local Congressmen made deals to bring in millions of federal dollars to improve the harbor. Evanosky says the big idea was to dredge a canal all the way across the north side of Alameda, turning the peninsula into an island.

We hear sounds of traffic near the canal

Dennis Evanosky: They planned to build this tidal canal as a scouring channel. What they planned to do was build a dam.

Pauline Bartolone: The dam would be built on the far east side of Alameda. And then during ebb tide, when the water is naturally flowing out to the Bay.

Dennis Evanosky: They are going to open that dam, and we’re going to have the water to, I say, “whoosh” through the scouring channel here.

Pauline Bartolone: Engineers thought this would harness the natural power of tides to flush sediment out of the Oakland estuary and toward the Bay, learning the passage for boats coming in and out of the narrow waterway.

Dennis Evanosky: And these aren’t necessarily big, huge ships. These could be smaller ships, but they need a place to navigate and turn around.

Pauline Bartolone: So, that was the plan. … in the beginning. The project got the green light in the early 1870s but had a slow start. And over the next three decades, it hit roadblock after roadblock. Early on, the government had to buy out 11 families who would lose part of their estates to the canal. They were offered $40,000 at the time, what is more than $1.2 million today. But one family refused.

Patty Donald: They were screwing with his kingdom. If you put it that way.

Pauline Bartolone: Patty Donald is the great-great-granddaughter of A.A. Cohen, a railroad industry baron and attorney who owned an estate with a 70-room mansion on Alameda. A.A. Cohen’s family challenged the canal project more than once.

Patty Donald: He was one of the most powerful people in Alameda at that time because he had started, he had bought a failing rail system in 1876, I think.

Pauline Bartolone: He sued to stop the canal project and lost. And it went forward.

Music starts

Pauline Bartolone: By 1889, the excavation was underway. But quickly suffered another setback. A deluge, literally. The winter that started in 1889 was one of the wettest on record. More than 45 inches of rain fell that year. That’s according to a history written by Woody Minor of the Alameda Museum.

Sound effect of typewriter under voice-over

Voice actor reading: Disaster struck on a stormy night in January when Sausal Creek overflowed its banks at Fruitvale Avenue and flooded the ditch and equipment. It took two months to pump out the water.

Pauline Bartolone: Then, they had to deal with public opinion. And perhaps the very first complaints from Alameda residents about commuting.

Dennis Evanosky: They are digging this canal. And there’s a problem. People complain, well, if you’re gonna have this canal here, how are we going to get home?

Pauline Bartolone: The canal dredging was disrupting traffic to one of Alameda’s main entrances, Evanosky says. So, the Park Street Bridge was built first, and then two other bridges came.. in the decade that followed.

Music starts

Pauline Bartolone: As if legal battles, payouts and flooding weren’t enough, the canal project suffered more roadblocks in the 1890s. According to the Alameda Museum’s Woody Minor, funding dried up during an economic depression. Then, the project’s long-time champion at the Army Corps of Engineers retired.

And then — this one’s big — new research suggested that dredging deeper in Oakland’s harbor would be more effective for boat passage than this idea of flushing sediment out using a dam. While government officials debated next steps, a partially dug unfinished canal was left. A big giant trench.

Dennis Evanosky: So they had to stop. And this is all done, and they had to stop.

Pauline Bartolone: Now, this is where the raw sewage comes into the picture. Right around this time, people in Oakland and Alameda started installing residential sewer systems. And the waste was flowing right into Lake Merritt and the Oakland Harbor. By the Alameda Museum’s account, the waterway became a cesspool.

Sound effect of typewriter under voice-over

Voice Actor: Fetid water awash with dead fish lapped against the dam and seeped into the ditch, emitting a pervasive stench.

Pauline Bartolone: Alameda’s health officer became the biggest crusader for completing the canal. In 1897, he argued that the stench from the incomplete trench had not only become offensive, but the foul water was killing fish and crabs and posing a health hazard.

So government officials soon found the money to put a massive steam shovel to work and finish that canal excavation once and for good.

Sound of a big machine starting up

Pauline Bartolone: In case you’re wondering if, during this era, anyone ever chimed in about the ecological impacts of ripping through this marshy area?

Richard Walker: No, no, no, no, no, it’s nothing like that.

Pauline Bartolone: Richard Walker says there wasn’t really an environmental movement at this time. Maybe an oysterman was concerned about declining catches.

Richard Walker: The conservationists at that time would be, I think, entirely obsessed with creating the first state parks. Saving the redwoods. They’re worried about mine debris in the Central Valley.

Pauline Bartolone: By 1902, the dredging was done. And 30 years after the plan was first hatched, the canal filled with water. Alameda was officially an island.

Residents in the city of Alameda were ready to celebrate.

Sounds of a marching band, crowd noise and fireworks

Pauline Bartolone: In September of 1902, there were days of fireworks, parades, brass bands, carnival acts, fancy diving and a procession of two hundred lighted boats.

Things were different from what was originally envisioned, of course. For one, there was no dam to help flush water out of the estuary.

Dennis Evanosky: In my view, they didn’t build the dam because they were just tired of this whole thing, and a lot of people didn’t think the dam was going to work anyway.

Pauline Bartolone: Now, more than a century later, as I walk along the canal with Alameda historian Dennis Evanosky near the Park Street Bridge, the canal water is relatively still. A few boats are docked, but none sail by. This neatly engineered waterway looks like a moat around a castle. It’s mostly used for recreation now.

Nate Puckett: This wasn’t natural. It looks very not natural.

Dennis Evanosky: Right? Right? Right, right.

Pauline Bartolone: Our question asker, Nate Puckett, has been walking with us, listening to Evanosky this whole time. He looks slightly unsettled.

Nate Puckett: So it sounds like the reason it’s an island was a failed idea.

Dennis Evanosky: Yeah, exactly. Yeah. I would say, “The island city, sort of.”

Nate Puckett: Yeah, yeah, the island city by accident.

Dennis Evanosky: Right, right. Right.

Pauline Bartolone: Nate clarified later that he found Alameda’s island origin story “surprising.”

Nate Puckett: You kind of always assume big projects like this are for a very clear and thought-out purpose. And to find that it was kind of an accident or the plan changed so many times is definitely surprising. Especially just, you know, because Alameda is so into being an island.

Pauline Bartolone: The fact that Alameda isn’t naturally an island doesn’t bother Nate Puckett too much now. After all, it’s been that way for a while, and residents here still bond over bridge and tunnel delays. And over a beer at Alameda Island Brewing Co.

Island-themed music starts

Olivia Allen-Price: That story was produced by Pauline Bartolone.

Big shout out and thanks to Liam O’Donoghue of the East Bay Yesterday podcast and UC Davis geographer Javier Arbona for their help on this story. Facts in this story came from Woody Minor of the Alameda Museum and historical documents from the Army Corp of Engineers and the National Park Service.

There’s still time to vote in our April voting round. Here are your choices:

Voice 1: I was recently at the Morcom Rose Garden in Oakland and saw three different official Oakland signs that read, “No glitter.” I would love to know what happened at the rose garden to warrant so many signs.

Voice 2: Yesterday, I walked with a fellow science teacher on the Great Hwy. We commented on the blackish sand, made of iron filings. Where does the iron come from?

Voice 3: Who are the de Youngs? I think they have some crazy stories!

Olivia Allen-Price: Vote for which question you think we should tackle next at baycurious.org. While you’re there, sign up for our monthly newsletter, ask your own question or get lost listening through the Bay Curious archive.

Bay Curious is made in San Francisco at member-supported KQED.

Olivia Allen-Price: Our show is made by:

Katrina Schwartz: Katrina Schwartz

Christopher Beale: Christopher Beale

Katherine Monahan: Katherine Monahan

Olivia Allen-Price: and me, Olivia Allen Price. Additional support from:

Jen Chien: Jen Chien

Katie Springer: Katie Springer

Cesar Saldana: Cesar Saldana

Maha Sanad: Maha Sanad

Holly Kernan: Holly Kernan

Crowd: And the whole KQED family.