Episode Transcript

Olivia Allen-Price: Every winter, Brian Teaff takes a chartered fishing trip from the Berkeley Marina to go fishing for Dungeness crab. They leave before dawn and motor out through the Bay, under the Golden Gate Bridge.

Music starts

Brian Teaff: There’s crazy stuff going on. I mean, there’s all kinds of water and it’s moving in all directions, and you can just tell the bay is just deep there.

Olivia Allen-Price: This winter, Brian stood on the boat and looked into the swirling abyss below.

Brian Teaff: Riding on the Bay going, there’s a lot of water that moves through here. And what’s underneath? I know there’s fish, what else is there? So it was just what’s underneath the water?

Olivia Allen-Price: Are there maybe … shipwrecks down there?

Brian Teaff: And then of course, you know, the next question is, oh, boy, I wonder if there’s any treasure down there.

Olivia Allen-Price: Treasure like precious metals, gems, valuable keepsakes. If you ask Brian to answer his own question, he says:

Brian Teaff: I think that it’s probably just full of mud down there. But boy, I’d like to know.

[Bay Curious theme song starts playing]

Olivia Allen-Price: Brian wrote to Bay Curious, to learn more about what’s at the bottom of the Bay. Today on the show, we’ll hear about two shipwrecks that haunt Bay Area lore. Plus, we’ll go searching for treasure and find it in something … unexpected. I’m Olivia Allen-Price. We’ll be right back.

Sponsor message

Olivia Allen-Price: Like many of us, KQED Reporter Anna Marie Yanny lives a short walk from the Bay. Like our question-asker Brian, she was eager to find out what’s down there.

Anna Marie Yanny: The first thing that came to my mind was the beginning of the Little Mermaid movie. Mermaid Ariel and her fish friend, Flounder, are diving in a shipwreck looking for treasures. Could there be any wrecks at the bottom of the bay?

[The Little Mermaid movie clip starts]

Flounder: Ariel, wait for me!

Ariel: Wow, have you seen anything so incredible in your entire life?

Anna Marie Yanny: I had to talk to James Delgado. He’s a renowned maritime archeologist and has worn many hats in the field. And back in the 70s, he was the first historian for the Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

James Delgado: Those early years at the park were magic because we were literally just new as a national park, and everything needed to be done. So, we conducted wide-sweeping inventories and explorations.

Anna Marie Yanny: He dove in the muddy waters of the bay in search of shipwrecks. And decades later, he mapped them with federal researchers, using sonar. I asked him just how many wrecks are in the Bay.

James Delgado: There’s probably several dozen that sit in and around the entrance to the Bay and in the Bay itself.

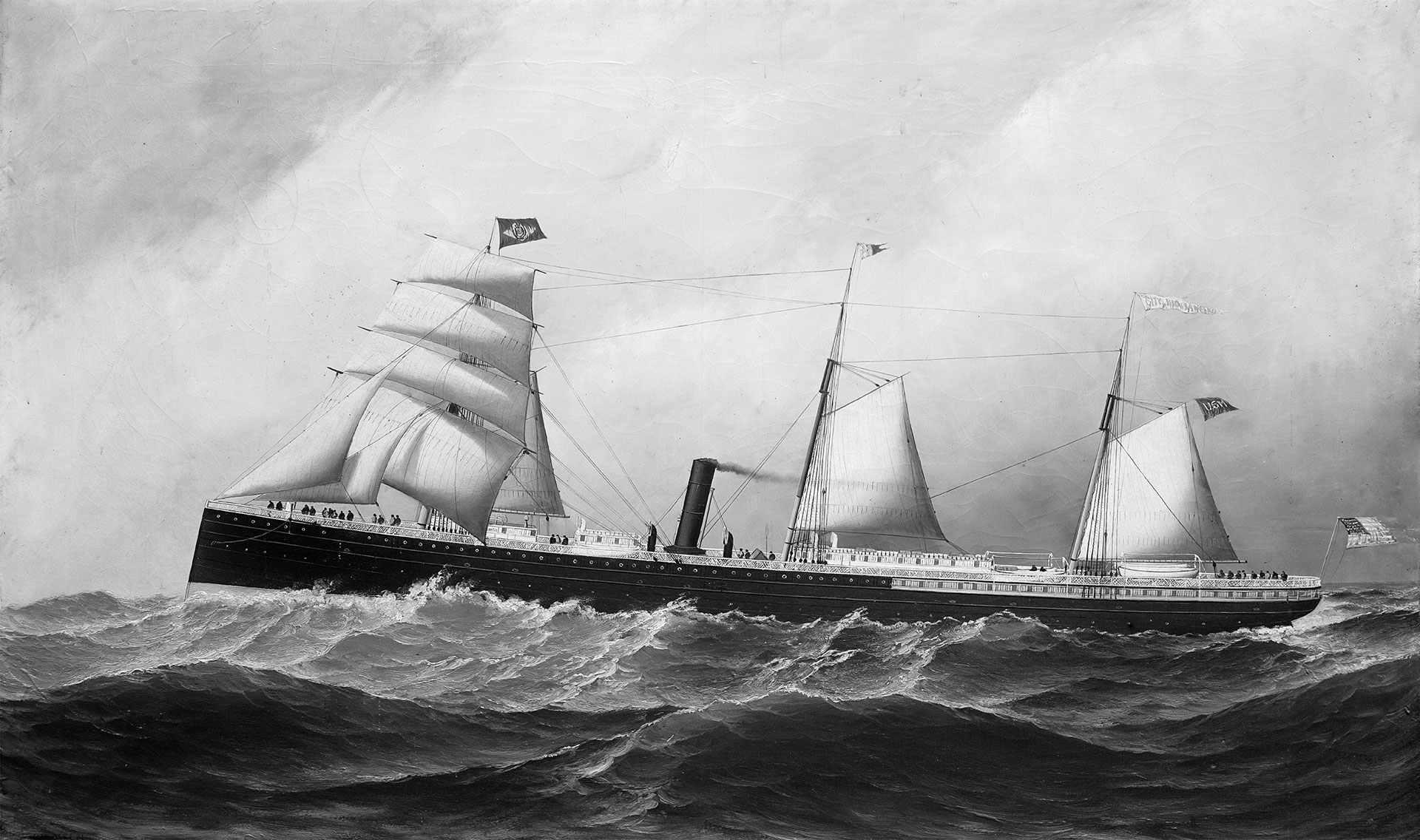

Anna Marie Yanny: A few wrecks stand out to him and other historians. He tells me about one of the deadliest, a steamship called the SS City of Rio de Janeiro. Named for the city in Brazil.

James and a team of researchers and underwater robots used sonar to relocate this wreck in 2014. It’s around five semi-trucks long and lies at the bottom of a deep channel west of Golden Gate Bridge.

James Delgado: The SS City of Rio de Janeiro was literally the Titanic of San Francisco Bay.

[Music starts playing]

Anna Marie Yanny: It was February 1901. The Rio was sailing to San Francisco from Asia [sounds of waves and wind] after an over two-month voyage to China, Japan, Hawaii. It was a big iron-hulled ship and had three masts, with sails billowing off them. Around 5 a.m., shrouded in fog, it headed towards Fort Point carrying more than 200 people — many of them Chinese and Japanese immigrants.

[Sounds of a collision]

James Delgado: It hit the rocks and backed off and sank so rapidly that many people who were still asleep in their cabins never had a chance to get out.

Anna Marie Yanny: Less than half the passengers survived. Many who did were saved by early morning fishermen. There’s photos of them gathered at Baker Beach.

James Delgado: The wreck itself disappeared. Though it remained intact enough that months later, the pilot house tore free, and in it was the skeleton of the captain, who was identified by his gold watch, which its chain had tangled in his ribcage.

Anna Marie Yanny: But no, he says there’s no more gold down there — maybe tin, but nothing salvageable.

In fact, I was told, many of those few dozen shipwrecks in and around the Bay are hard to reach. They’re covered in mud that ran down from the Sierras during the Gold Rush or near currents rushing in and out of the Bay.

I wanted to know what other shipwrecks sat in the fathoms below, so I went to the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park.

[Sounds of waves, seagulls]

Anna Marie Yanny: The park sits on the water across from Ghirardelli Square. It has a ship-shaped museum and a visitor and research center dedicated to West Coast maritime history.

I’m here on a foggy morning. It’s cold. Brave open-water swimmers glide past these pirate-ship-looking boats docked at Hyde Street Pier. Each of the ships have narrowly avoided becoming wrecks themselves, and are instead retired in the park, and open to visitors on the weekend.

Anna Marie Yanny in tape: Wow, this is awesome. I can’t believe I haven’t been yet.

Christopher Edwards: We can certainly sort of get a feel for the place, take a walk through. We could also…

Anna Marie Yanny: Park Ranger Christopher Edwards lets me into the Visitor Center.

There, he tells me about another wreck. An oil tanker called the Frank H. Buck. He brings me back to the day of the wreck.

Christopher Edwards: It was like a worse version of today. You know, today we’ve got sort of the classic morning San Francisco fog.

[Sounds of foghorns, water lapping, creaking boat]

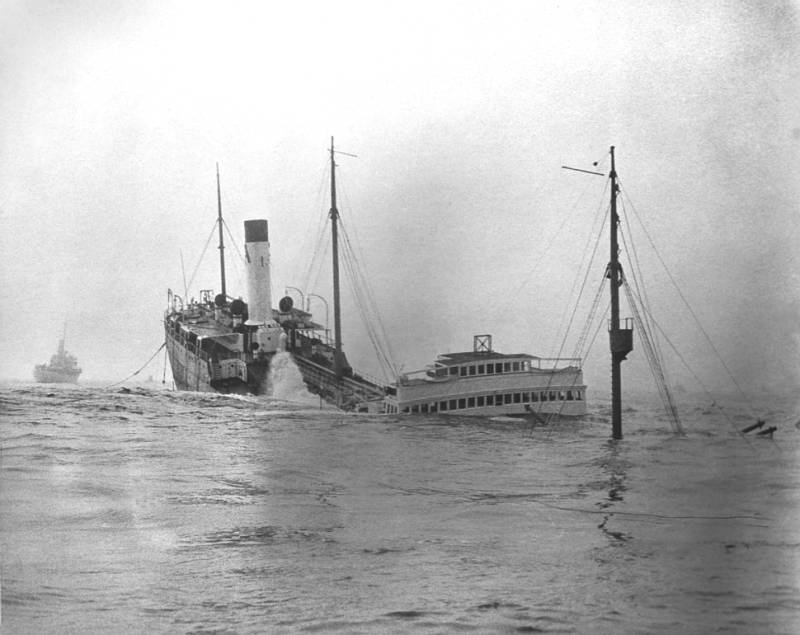

Anna Marie Yanny: It was March 6, 1937. The Frank H Buck tanker was coming into San Francisco Bay with oil from just down the coast, in Ventura.

Christopher says it was a working ship, and the 30 to 40 person crew were probably dressed in modest work clothes. And nearby, the SS President Coolidge was a luxury liner carrying about 700 passengers headed outbound…west towards Hawaii, then Japan.

There, Christopher says the few-hundred-person crew were dressed in uniform, and the ship was organized by class — with the low-ranking crew traveling through below-deck passages to avoid disturbing the passengers. On that foggy day, both ship’s crews were using foghorns.

Christopher Edwards: But the Golden Gate, which is the entrance into the bay, you know, it’s steep sided. And so those foghorns help, but the sound bounces around off the terrain. And it just makes it really difficult to know precisely where you are.

Anna Marie Yanny: They both reached the Western side of the Golden Gate Bridge.

Christopher Edwards: And until the last minute, they didn’t realize they were going directly at each other. And everything happens in slow motion with a ship. You can tell that a disaster is about to happen. But as soon as you realize that that disaster is happening, it might be too late to do anything about it.

Anna Marie Yanny: The ships collided. Nose to nose. The lookout at Lands End said it sounded like a booming Presidio gun through the fog. The luxury Coolidge punctured the Buck. And it’s Captain thought fast.

Christopher Edwards: He didn’t want to pull his ship back immediately and realized deliberately that if he did that, the Buck could sink very quickly.

Anna Marie Yanny: The Coolidge captain shouted to the Buck captain. They were that close. They got everyone off the Buck. The crew was loaded into lifeboats and paddled away from the ship before the Coolidge backed away.

Christopher Edwards: The photographs, what they seem to capture is just the crew knowing what they needed to do and ensuring that nobody got hurt, nobody was left behind.

Anna Marie Yanny: What was left behind was the massive body of the Frank H Buck, which began sinking, nose down. It was carried by currents to the rocks off Lands End. Oil pooled out of it, like blood, from the once hearty vessel.

The body of an oil tanker likely didn’t have any treasure. And honestly, Christopher says, the bottom of the bay probably doesn’t have the type of treasure our question asker Brian was asking about.

Christopher Edwards: What’s underneath? Is there gold? Is there other precious valuables down there? To the best of my knowledge. The short answer is no. But there’s a treasure down there. I’d say absolutely.

Anna Marie Yanny: Christopher says, despite there being no gold, we have a lot to learn from wrecks like these.

Christopher Edwards: There’s archeological treasures down there. There’s stuff that tells you that somebody just like you existed there, that was their home, that was their community.

Anna Marie Yanny: I thought back to Ariel in The Little Mermaid. To her, treasures were relics of the human world. Candlesticks, wine stoppers…a fork. Hints of a world that wasn’t hers, but could have been.

To Ariel — and to Christopher — and maybe to many of us — history is its own kind of treasure. Not the type our question asker hoped for, but something of value nonetheless.

On our way out, Christopher shows me a model of the entrance to San Francisco Bay, complete with a hand-sized Golden Gate bridge. Along the entrance to the bay, the names of about 50 wrecks are written in red. All their graveyards. All little ghost towns. All ships that needed to move between the big, open ocean and the thin ship channel that enters San Francisco Bay. All ships that didn’t quite make it. But still have a story to tell.

[Music playing]

Olivia Allen-Price: Wow! I had no idea about those shipwrecks. But I do wish there had been some gold, though.

Anna Marie Yanny: Yeah, I asked around and seriously, no. Maybe flecks of gold mixed in with the sediment.. leftover from the Gold Rush, but nothing worth trying to collect.

And it could be dangerous trying to reach some of these shipwrecks — James says the first team that tried to reach the Rio wreck lost their robot because of the strong currents down there.

Olivia Allen-Price: That also sounds super costly!

Anna Marie Yanny: But to James and Christoper, it sounds like the treasure really is the history, and how it can help you picture the life that someone else had. Also….there’s another treasure learned about that I wanted to tell you about.

Olivia Allen-Price: What’s that?

Anna Marie Yanny: The other treasure is….Mud

Olivia Allen-Price: Mud?

Anna Marie Yanny: Mud. Go with me here.

Until about 15 years ago, environmentalists thought of mud as a nuisance in the bay. It flowed in from urban development, watersheds and mining through the mid-18 and 1900s.

Julie Beagle: Macroinvertebrates couldn’t live, and there wasn’t enough food for the fish and really clogged important spawning habitat.

Anna Marie Yanny: That’s Julie Beagle. She’s an estuarine geomorphologist. Meaning she studies how water and sediment move to shape estuaries like the Bay.

Julie Beagle: The idea of keeping sediment, keeping development out of the Bay was really the guiding principle for a long time.

Anna Marie Yanny: But around 2011 Julie and her colleagues began to change how they think about mud. They’d been successful at keeping it out. But, between that and some natural fluctuations, there was a new problem. With less sediment being deposited onto the bay’s marshes, sea-level rise was threatening to erode them away. Suddenly, mud didn’t seem so bad.

Julie Beagle: Sediment is this treasure that we need to keep. We need to maintain it in the system.

Anna Marie Yanny: Not pirate treasure like our question asker wanted, but certainly treasure to scientists. The bay’s marshes don’t just provide good views and habitat for endangered species, they also protect bay neighborhoods and highways from flooding by blocking storm surges and absorbing floodwaters.

Julie Beagle: As we adapt to sea-level rise, I think the world has this choice. Are we going to adapt with walls, with rock, with riprap.

Anna Marie Yanny: Or do we adapt with natural infrastructure, like marshes? To rebuild marshes that are at risk of drowning from sea-level rise, Julie and her colleagues would need a lot of this — now treasured mud — from the bottom of the Bay.

They turned to the local district of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, who regularly dredge the mud in ports so ships can navigate the Bay. Julie applied to work for them.

Julie Beagle: Part of the reason I switched to the Army Corps is I said, who has the sediment, and how can we get that sediment to the places that it needs to be.

Anna Marie Yanny: Now, she helps lead their “Engineering with Nature” team. Along with the Corps and collaborators at the USGS and other local and government partners, Julie is using mud in pilot studies. They’re hoping bay marshlands can be built back up with routine doses of mud from the bottom of the bay. They tried this method for the first time in December.

Julie Beagle: We placed 90,000 cubic yards in 169 trips. So the boats were going back and forth 24 hours a day.

Anna Marie Yanny: Down at the Port of Redwood City, a dredge with a clamshell mouth loaded a flat bottom boat over and over until it was full.

[Sound of a crane dumping mud into a boat]

Anna Marie Yanny: Then a tugboat pushed that boat just across the Bay

[Sound of boat motor]

Anna Marie Yanny: To the shores of Eden Landing, near Hayward. There, Julie says, the marshes have been eroding. Ponds behind it have been breached.

[Sound of boat moving]

Anna Marie Yanny: The boats reached about a mile offshore. It was a spot strategically chosen so the sediment will be carried towards the marshes by waves and tides naturally.

Julie Beagle: And then the bottom just opens up and the sediment just comes down. And it happened so fast. It’s like 13 seconds. It was just like a “juh–zoupp!”

Anna Marie Yanny in tape: So. the bottom of the boat just opens?

Julie Beagle: The bottom of the boat just opens

Anna Marie Yanny in tape: No way

Julie Beagle: It places the material, and then the boat would go back and get another scow and come do it over and over again.

Anna Marie Yanny in tape: One hundred and…?

Julie Beagle: 169 times. 24 hours a day. They took Christmas off.

Anna Marie Yanny in tape: Wow, that’s incredible.

Julie Beagle: And I’ve never been so excited to move dirt from one place to another in the Bay, you know?…

Anna Marie Yanny: The boats went back and forth nearly the whole month of December. Julie says if the pilot achieves its goal, and the marshes stay healthy and fortified against sea-level rise, she hopes to someday give them regular boosts of mud every few years.

So, there you have it. There is treasure at the bottom of the Bay, just maybe not the type you expected.

But if the history down there ties us to our past, and the mud helps us ensure our future, maybe that’s more valuable than gold. Although, some gold would have been nice.

Olivia Allen-Price: That was KQED’s Anna Marie Yanny.

Thanks to Brian Teaff for asking this week’s question. And thanks to Peter Pearsall from the USGS for the boat sounds from Julie’s mud pilot project.

If you’ve got a question you’d like to hear answered on Bay Curious, head to BayCurious.org and ask! While you’re there, sign up for our monthly newsletter, where we often answer even more listener questions than we can get to on the podcast. Again, it’s all at BayCurious.org.

We are off next week for the July 4 holiday — back in your podcast feeds on July 11.

Brian Teaff: Bay Curious is made in San Francisco at member-supported KQED.

Olivia Allen-Price: This episode was edited by Kevin Stark and me, Olivia Allen-Price.

Katrina Schwartz: Produced by Katrina Schwartz.

Christopher Beale: And me, Christopher Beale.

Olivia Allen-Price: Special shout-out this week to Chris Egusa.

Paul Lancour: Additional support from Paul Lancour.

Everyone saying their own name: Jen Chien, Katie Sprenger, Cesar Saldana, Maha Sanad, Holly Kernan.