“We just have made very little progress since 2019,” said Fuller, an education and public policy professor at UC Berkeley.

Early childhood education in California has long been a patchwork of government-run preschools, private and nonprofit centers, and family child care sites that are run out of providers’ homes. The state typically pays for children from the lowest-income homes. An example is vouchers that give parents the option of putting their kids in a center or at home, under the care of a provider, family member or friend.

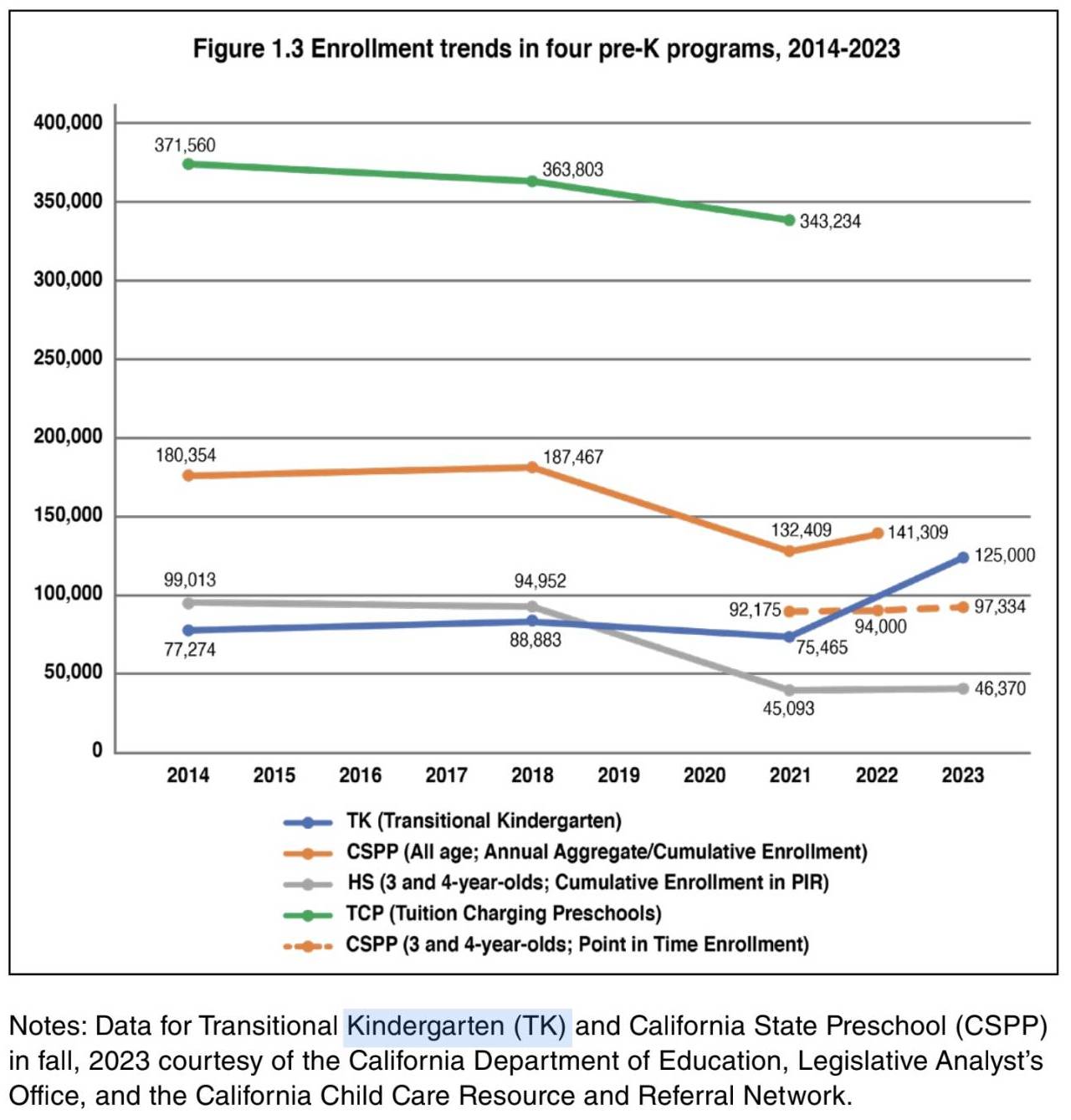

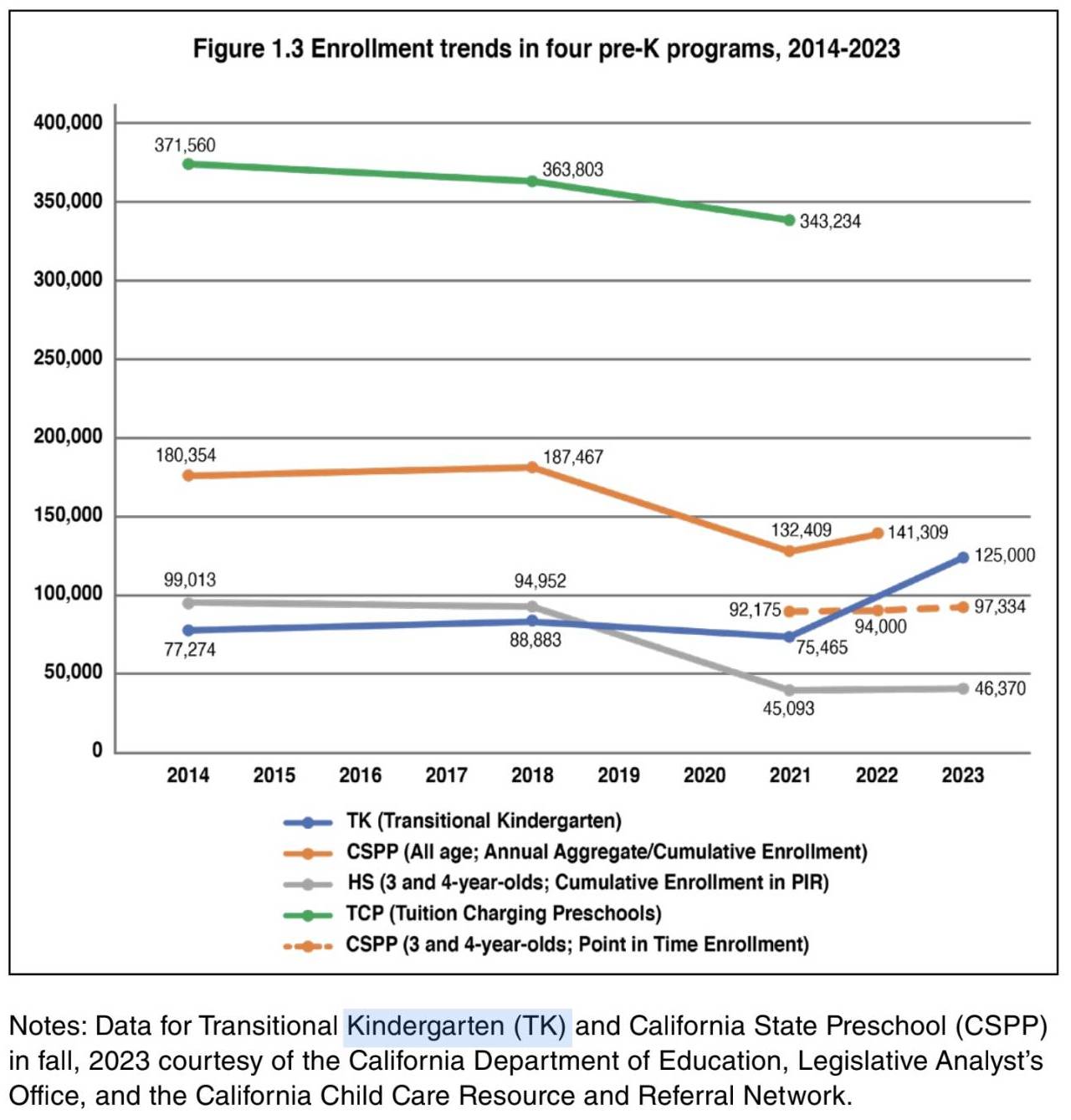

When lawmakers signed off on a $2.7 billion plan to make transitional kindergarten, or TK, available to all 4-year-olds by the 2025–26 school year, experts warned it would take away students and teachers from other early childhood education programs, including private preschools because it’s free and offers teachers better pay and benefits.

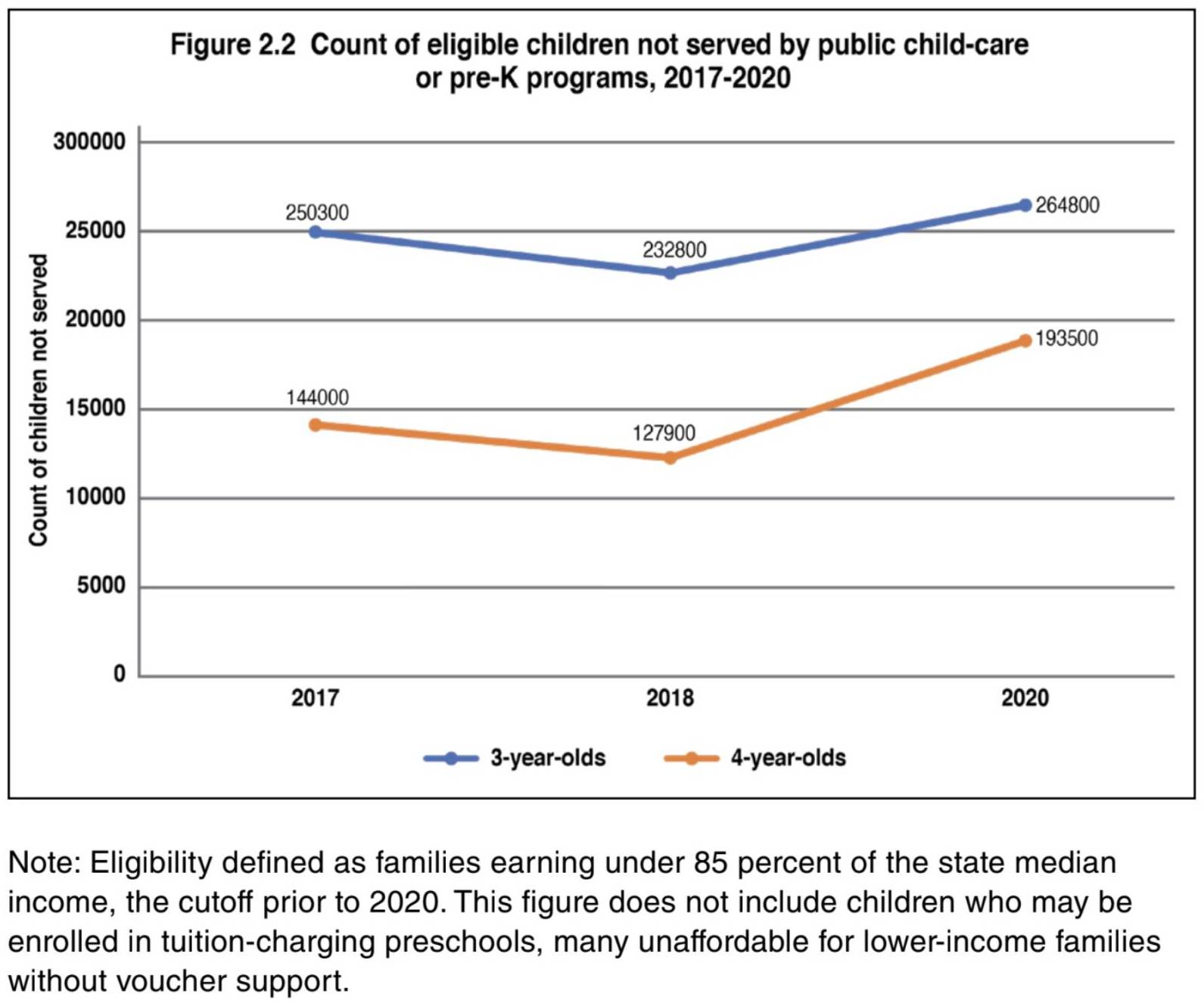

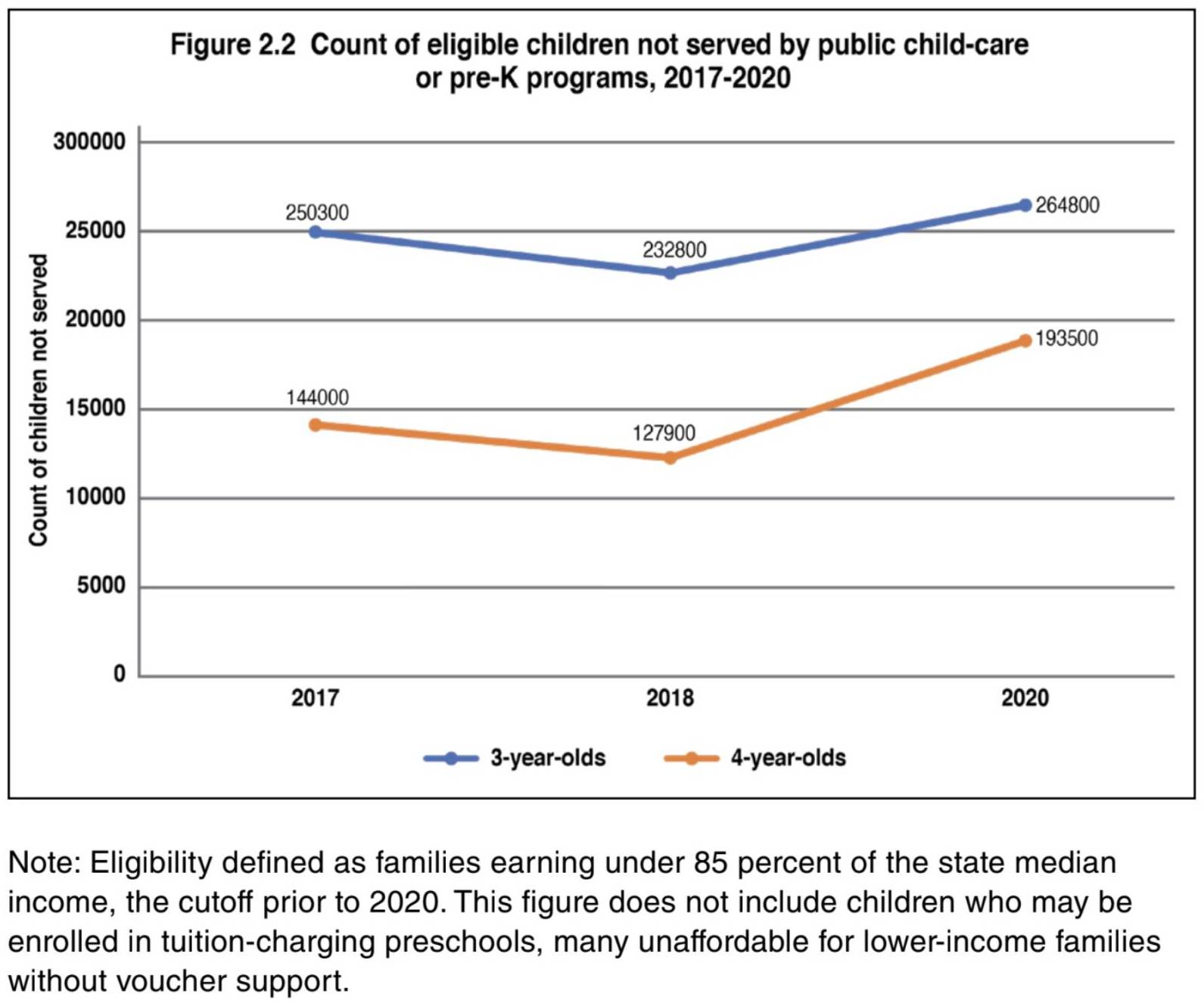

The state responded to that concern by expanding the California State Preschool Program and widening access to that program for 3- and 4-year-olds from lower-income households. The state focuses on this population because research shows (PDF) that kids from lower-income households gain more academic and social skills and benefit more from two years of participating in a high-quality preschool program than kids from more affluent households.

But Fuller said these policies contradict each other and add more confusion to what he calls a “crazy quilt of programs that’s hard for parents to understand.”

Fuller points to a 20% jump in vouchers between 2021 and 2023, indicating a growing preference for child care arrangements that offer parents more choice and flexibility but discourage them from signing up for preschool.

Child care advocates say the popularity of vouchers points to a greater need for child care that matches families’ individual needs, whether during irregular hours for those who work weekend or night shifts or in a setting that aligns with their cultural or linguistic preferences.

“Just because you build (a preschool program), people will not come,” said Linda Asato, executive director of the nonprofit California Child Care Resource & Referral Network. “It may not make sense for families. When setting that goal of universal TK, it can’t be done in a vacuum because it may not be what everyone wants.”

Meanwhile, a pandemic-era “hold harmless” policy, which guarantees a certain level of funding regardless of the number of children enrolled, may have had an unintended consequence for California State Preschool programs.

“During COVID, those programs continued to get the same budget they had in 2019,” Fuller said. “Initially, that was sensible because you didn’t want to start laying off staff and closing down preschools, but it also doesn’t create an incentive to move towards [enrolling 3-year-olds] because why not have smaller classes, and maybe bump up your salary a little bit?”

As a result, $713 million in unspent California State Preschool Program funding was returned to the state coffers, according to a summary of the 2024–25 state budget (PDF).

Al Muratsuchi, who chairs the state Assembly’s education committee, acknowledges the expansion of TK is disrupting other programs and that more work needs to be done to inform parents about their options and ensure there are enough workers and facilities to provide a high-quality early childhood education for all kids.

“We are in a transitional period,” said Muratsuchi, a Democrat from Torrance.

The analysis also identified zip codes that are populated with young kids but don’t have few, if any, public preschool programs. They include parts of the Central Valley and Central Coast, plus fast-growing working-class suburbs like Antioch and Livermore in the Bay Area. Fuller said these communities lack the “civic infrastructure,” like community-based organizations or school districts, to bid for state funding for a preschool program.

He hopes the analysis will compel state officials to target funding on families that have almost no preschool options in their community and simplify the child care and early education system for parents.

Muratsuchi thinks one possible solution is to further invest in community schools that provide a variety of social support services for students and their families on campus, and those services could include childcare and preschool programs.

“We need to continue to build upon this community school model and take advantage of the existing public school infrastructure,” he said.