All of this happened within four seconds, though some devices might not have picked up the notification for a few more.

“It’s doing everything really, really fast. And the goal is simply to warn as many people who may feel shaking, particularly strong shaking, as much as we can,” she said.

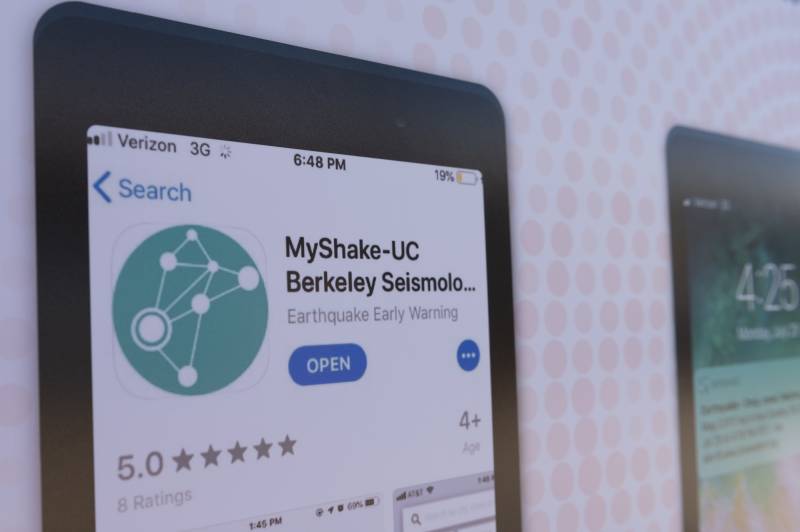

Unlike main seismic networks that determine magnitude after a quake, the MyShake app uses a very small sample of data and works very quickly, she said. This means that sometimes, the initial detection might slightly miscalculate the magnitude, but it recalibrates quickly.

Getting a warning before an earthquake still feels unusual — Californians have learned from a young age that they’re unpredictable and come on quickly. The idea of an early notification feels impossible — and in some cases, it still is.

“If you’re right on top of the epicenter and you are closer than our four closest stations, you will probably not receive a warning before you feel the shifting,” Lux said. That area is called the late alert zone.

“Studies that show that this can still be useful to people because sometimes, especially if it’s not as big of an earthquake, sometimes that initial p wave, people kind of feel and they look around and be like, ‘Do you feel that?’ But if you have that alert come in, you’re like, ‘Oh yeah, it is an earthquake.’”

The farther from the epicenter you are, the longer the warning time you can usually get. Lux said the instructions for people who get the notification are the same: duck, cover and hold on.

“We’ve seen that for many earthquakes, particularly on the West Coast, in California, the people that are injured are injured by things falling on them because they’re trying to get to safety,” Lux said. “It’s really hard to move during an earthquake.”

While the recent string of earthquakes doesn’t mean much in terms of lessening tectonic pressures or subduing the Big One, installing early detection technology on your smartphone and taking other preparedness measures like making an emergency kit and coming up with a household plan might make you safer if one does hit.

KQED’s Billy Cruz contributed to this report.