Emmy Award-winning filmmaker and MacArthur fellow Jon Else is known for films like The Day After Trinity: J. Robert Oppenheimer and the Atomic Bomb, Yosemite: The Fate of Heaven and Cadillac Desert. Else’s new film, Land of Gold, is a behind-the-scenes documentary about what it takes to bring an opera to the stage. It’s also the complicated story of Girls of the Golden West, an opera whose plot hinges on the true story of Josefa Segovia, a Mexican American woman who killed a gold miner in self-defense in 1851. On July 4th of that year, an angry mob lynched Segovia over the Yuba River in Downieville.

The California Report Magazine’s host, Sasha Khokha, sat down with filmmaker Jon Else to talk about Land of Gold, which premieres on the PBS series Great Performances this week.

Below are excerpts from their conversation. For the full interview on The California Report Magazine, listen to the audio at the top of this story.

On deciding to make Land of Gold

Jon Else: I had done films before with the composer John Adams, and John contacted me and said, “I’m going to do an opera about the Gold Rush. Do you want to make a movie about it?” I was not interested! I grew up in Sacramento in Gold Rush country. I was heavily schooled in the cleansed version of the Gold Rush. I thought I knew it all — kind of been there, done that — and I was just not interested.

Then John said, “Well, we’re basing it on a diary by a woman named Louise Clappe, who was one of the very few women in the gold fields during the Gold Rush in a hardscrabble, rough-and-tumble little mining settlement called Rich Bar.” John said, “Why don’t you read the diary?”

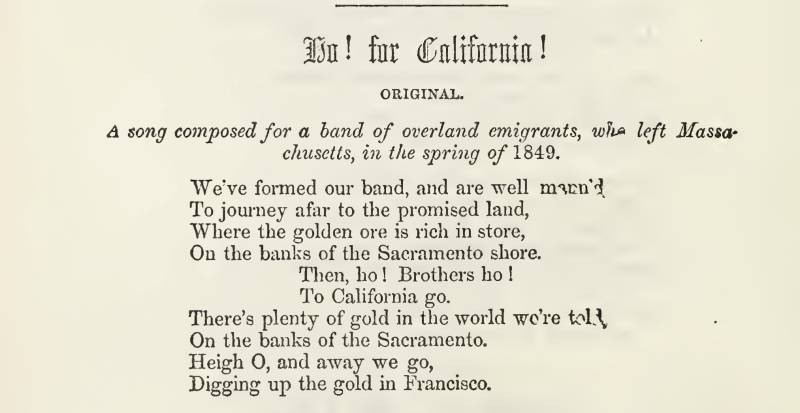

I read the diary, and I was flabbergasted. It was all the history I had not been taught in my public school in Sacramento. It turns out it was hell for most of the people involved who were not white Anglos. It was terrible for women. It was terrible, of course, for Native Americans.

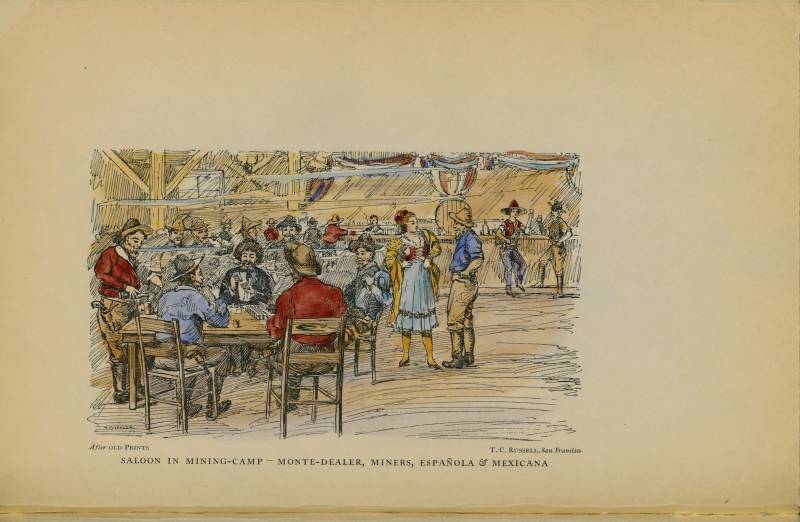

Also, what was new to me was the notion that the Gold Rush was this tremendously diverse migration. Miners came from Polynesia, they came from France, from Germany, from Mexico, from China. There were a lot of Canadians. There were freed slaves. The California gold fields were this huge rainbow of folks. Now, it was not a rainbow of equity. The white guys were in charge, and it was very, very tough on everyone else.