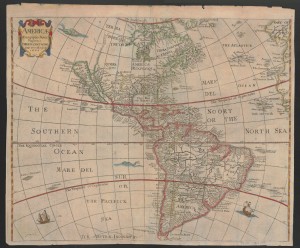

To some, it seems a mere technicality that California is attached to the rest of North America. It's not just a fantasy held by liberals keen to disengage from national politics, or by conservative pundits keen to dismiss our inexplicably robust performance in culture and business. The idea of California as separate, special, has been with us for centuries.

The misconception began in 1510, with a Spanish novel by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo. He set imaginations afire with Las Sergas de Esplandián, an international bestseller in its day.

I tell you that on the right-hand side of the Indies there was an island called California, which was very close to the region of the Earthly Paradise. This island was inhabited by black women, and there were no males among them at all, for their life style was similar to that of the Amazons.

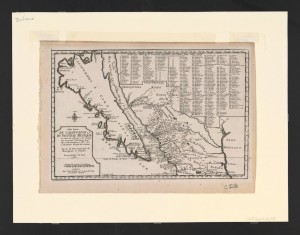

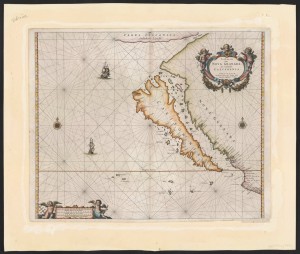

Montalvo's description was so compelling that Spanish explorers set off to find this earthly paradise, and insisted on the author's vision despite what they saw with their own eyes. Now at Stanford University, there’s a collection of about 800 maps from the 17th century that feature this curious coda in history.

The guy who collected those maps is Glen McLaughlin. He became interested in maps about 42 years ago when, as Finance Director of Memorex Europe, he was sent to work in London. Poking around shops near Harrods, McLaughlin and his wife found a map that showed California as an island, “something I’d never seen before.”

Forty years later, the collection that chance discovery inspired came to Stanford's Branner Earth Sciences Library and Map Collections. McLaughlin's collection is believed to be the widest, broadest, deepest collection of its kind anywhere. It’s a fascinating survey of the human will to resist data that conflict with what we want to believe - or our loyalty to what we have come to believe, based on limited information.