There are a handful of ways that one can deal with a deceased actor in post-production. In Heath Ledger’s last unfinished film, The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus, other actors were brought in and lines were redistributed. In Bruce Lee’s last film, Game of Death, body doubles performed stunts wearing wigs and sunglasses. When Lee had to look in a mirror, the double gazed at a cardboard cut-out. The manipulation of the image of a dead actor breaks down some deep taboos about respect for the dead, especially respect for dead bodies. Attempts to graft the moving face of a posthumous actor onto a body double ignite these same taboos: think the crass recycling of deleted footage from the first three Pink Panther movies to stitch Peter Sellers into a fourth installment, though he died 18 months before the film went into production. There’s also, of course, the ambivalently received posthumous editing of Nancy Marchand into The Sopranos or Oliver Reed in Gladiator.

Lionsgate has clearly opted to avoid these latter, loaded solutions. In an interactive promotional packet, director Francis Lawrence and writer Nina Jacobson are clearly responding both to the negative history of technology in posthumous acting and to earlier press materials that made it sound like a CGI Hoffman would star in Mockingjay: Part II. Lawrence explained, “We finished the majority of his work. I think he might have had 8 to 10 days left on our schedule. In most of those scenes, Phil didn’t have any dialogue. We are going to put him into those scenes, but we’re only using real footage. We’re not creating anything digital or a robotic version of him.” Jacobsen continued, “We might give a line of Plutarch’s to Haymitch or Effie, but only in circumstances that we are able to do that without undermining the intent of the scene.”

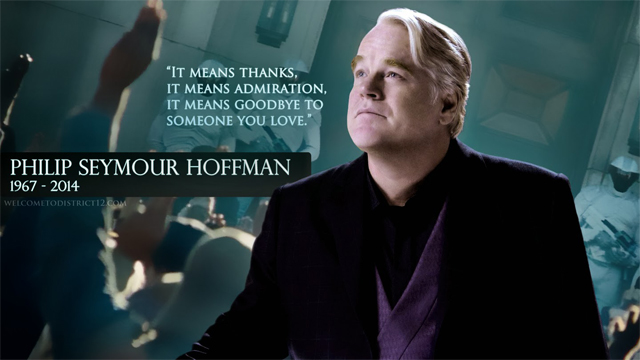

Part of this reactionary, anti-tech stance must come from Hoffman himself. Philip Seymour Hoffman was an “actor’s actor.” As A.O. Scott stresses, “As the heavy, the weird friend or the volatile co-worker in a big commercial movie he could offer not only comic relief but also the specific pleasure that comes from encountering an actor who takes his art seriously no matter the project. He may have specialized in unhappiness, but you were always glad to see him.” The assumption that the Mockingjay movies would form Hoffman’s epitaph seems off-putting, no matter how much gravitas, humanity or professionalism he brought to the role. To digitally simulate Hoffman’s performance would undo not only the work of one film but of his entire career.

But choosing to leave Hoffman’s performance intact only makes it all the more ghostly. His opening speech in the trailer, the cut to Hoffman waggling his eyebrows: it is this humanity and liveliness that makes the movie so haunted. Though the actor dies, the character can and must live without him. And so in sticking to Hoffman’s recorded material, and insisting that the film will represent his talent largely intact, the director and producers stress acting as an important part of the fantasy world of Panem, acting that is embodied, personal, dynamic, even "live". The trailer successfully hypes the film’s performances. I, for one, am looking forward to see Julianne Moore, Jennifer Lawrence, and especially Philip Seymour Hoffman. But the unmediated, character-driven realness of the end of the Hunger Games series reminds us that we will never really look forward to another Philip Seymour Hoffman movie again.