Compared to the more modern and much racier Go The F**k to Sleep, Margaret Wise Brown’s Goodnight Moon, with its bunnies and primary colors, feels super kid-friendly. And yet: Brown once said, “I don’t especially like children...At least not as a group. I won’t let anybody get away with anything just because he is little.”

Surprised? So was Slate's Katie Roiphe: "I had been picturing [Brown] as a plump, maternal presence, someone like the quiet old lady in the rocking chair whispering, “Hush,” and so I was surprised to see, in a bored, casual dip into Google, the blonde, green-eyed, movie-starish vixen, and attendant accounts of her lesbian lover, her many male lovers, her failure to settle down, and tragic early death.”

Brown wasn’t the only “wild child” of the picture book bunch. Unsurprisingly, the author of the vivacious Eloise books, Kay Thompson, “gave voice to MGM's musicals; [served as] a legendary vocal coach for the likes of Frank Sinatra, Lena Horn, Marlene Dietrich and Lucille Ball; [was] a fabled friend and mentor to Judy Garland and Liza Minnelli; [became] the actress who stole a film from under the feet of Fred Astaire and Audrey Hepburn; and the most popular and highest-paid cabaret performer of all time.”

Of course, we mustn't forget the legendary curmudgeon-esque qualities of Maurice Sendak, whose late-in-life interviews (Part 1 and 2) with Stephen Colbert upset some people’s notions of how authors for kids should be.

The Inspiration for Beloved Books

Some classic books come from dark places.

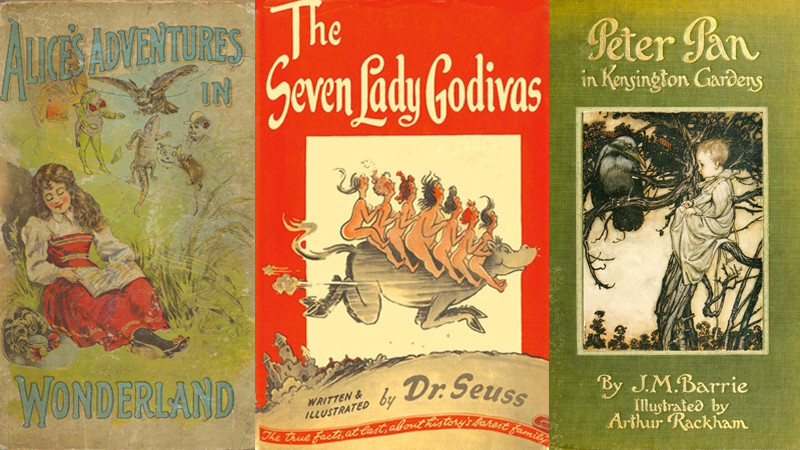

Academics and parents alike have been puzzled by the Oxford mathematics teacher Rev. Charles Lutwidge Dodgson’s (better known as Lewis Carroll) unorthodox friendship with a young girl called Alice Liddell, who served as the inspiration for his most famous work, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, published in 1865.

The story behind J.M. Barrie’s story Peter Pan involves the heartbreaking loss of Barrie’s 13-year-old brother in a skating accident. His mother could not be consoled and Barrie did everything he could to fill his brother’s shoes (including dressing in his clothes). The experience made him realize that leaving childhood was life’s greatest tragedy, which led him to tell stories about a boy named Peter Pan who never grew up.

Much has been written about how Margret and H.A. Rey of Curious George fame (both German-born Jews) fled Paris and the impending Nazi occupation on bicycles in June 1940, the early drafts of a manuscript tucked in their belongings. While trying to find safe passage to the U.S., the Curious George manuscript helped save them. When questioned by officials curious about their German accents, they simply showed that they were innocent children’s book writers trying to find new, safer lives.

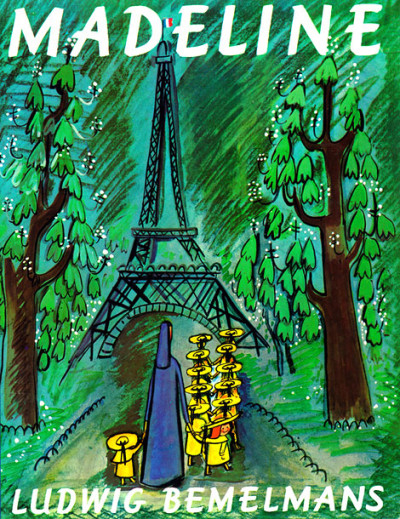

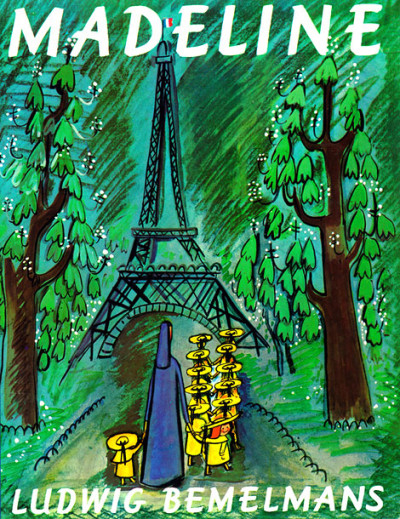

Ludwig Bemelmans' Madeline, published the week before WWII began in 1939, has slightly darker undertones. Bemelmans hid some dark secrets in the book. The caregiver for Madeline, Miss Clavel, was inspired by this sad story:

“[When] Bemelmans was a little boy in Austria, French governesses wore severe garb, like nuns. It was supposed to be unsexy, to keep the children’s fathers away…But Ludwig’s father was a real hound. Lambert Bemelmans got the family governess pregnant, and his wife as well, then ran off with another woman — all when Ludwig was about Madeline’s age. The boy was shunted off to school in Germany. And the governess, whom he adored, committed suicide.”

Later in life, Bemelmans wrote to Jacqueline Kennedy about his work: “For me, Madeline is therapy in the dark hours.”

So I guess the lesson of all these stories is to not judge a book by its cover...or intended audience.

Know of any interesting children's book backstories? Leave them in the comments.