Even as a kid I was reasonably aware that many of my favorite shows were essentially extended commercials for cheap plastic toys. From GI Joe to Transformers to Popples, the ‘80s and ‘90s had a grand tradition of cartoons that introduced new characters and accessories with attendant toy tie-ins on a near-weekly basis. That aspect hasn’t changed a whole lot, but the way shows go about it has.

Consider a show like Ninjago, a series in which the characters, buildings and vehicles are all made of Lego. Consumer tie-ins don’t come much more blatant than that, and yet Ninjago does a lot more with its tools than you might expect. The show tells a fast-paced, consistently entertaining story of a modern-day ninja team battling evil and discovering themselves. The plotting is serialized and fairly complex, but not so much that it goes over the heads of the target audience.

It’s storytelling that would work in nearly any medium. In this case, the medium happens to be computer-animated Lego. If that means they wind up selling a few thousand more building sets (they’ve certainly placed a few in my home), kudos to the marketing team. That doesn’t change the fact that the creative team has crafted a compelling narrative that’ll stick with the kids long after the toys are shunted to the closet.

I’m not calling Ninjago a masterpiece—it’s still a goofy action comedy about Lego ninjas—but it’s a heck of a lot better than the days when He-Man would battle a test-marketed villain for 15 minutes and move on to something unrelated and equally sellable in the next episode.

That’s the overarching theme I’ve discovered with many of today’s kids’ shows: they’re better than they have to be. Sure, there have always been kids’ shows that go the extra mile—it’s no coincidence that the best episodes of The Real Ghostbusters and Ducktales have stuck in my memory far longer than, say, Police Academy: The Series or The Super Mario Bros Super Show. But the bulk of 1980s cartoon programming seemed to be the work of jaded writers who assumed kids were dumb and would watch whatever was put in front of them.

And heck, to some extent they were right (I know I willingly sat through more than one episode of Turbo Teen as a youngster). But that was also a time of limited availability. Your options for kids’ programming were mostly confined to the big three networks’ Saturday morning fare and whatever got slapped in the 3pm to 5pm slot after school. Creators had the luxury of being lazy because what else were the kids gonna do, go outside and play?

As choices ballooned in the era of broader cable and internet access, the stakes got higher. At the same time, YouTube opened up rabbit holes of nostalgia viewing that allowed former ‘80s kids to relive their childhood TV favorites and come to the sobering realization that they mostly sucked. By the time my generation started reproducing, entertainment companies had some compelling reasons to invest in a certain standard of quality.

It’s paid off, too. I’d argue that we’re in a golden age of kids’ cartoons. In the past, a spin-off of a popular movie series like, for instance, Dreamworks' Dragons would have plunked a few familiar characters into a series of interchangeable adventures with new, toy-friendly dragon designs and accessories every week. Instead, Dragons is full of ambition and world-building, with considerable character development independent of its source material.

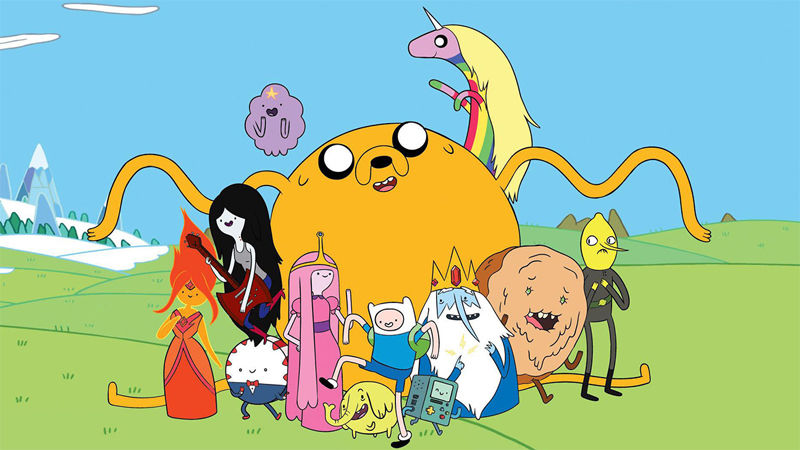

Reboots like the aforementioned TMNT and My Little Pony have earned respect (and, in the latter case, an infamously devoted adult following) by pushing beyond the test-marketed pablum of their forebears with sharpened writing and inventive design. And that’s not even getting into the realm of wonderfully weird original programming like Adventure Time, Steven Universe and The Amazing World of Gumball, shows that consistently break ground and are as beloved by teens and grown-ups as they are by kids.