Breanna Sinclairé doesn't look like your stereotypical opera singer. First of all, she dons neither metal brassiere nor matching horned helmet and she's not in the least bit the Wagnerian "fat lady" of yore. With her long, straight hair and eclectic wardrobe (usually completed with faux fur booties), she's the kind of girl you see on Valencia at all hours. If not for her occasional soprano trills to illustrate a point, you might not ever know she was a classical voice major at San Francisco's Conservatory of Music and, if you didn't stop and listen to her story, you definitely wouldn't know about the new ground Breanna is breaking in the opera world.

The 24-year-old is, by her own estimates, one of the few (if not the only) trans singers currently studying classical voice at a major music conservatory in the United States and has already received attention from The Wall Street Journal and Out Magazine among others for her unique story. Yet again, San Francisco breaks new ground: this time in the very traditionally minded world of classical voice.

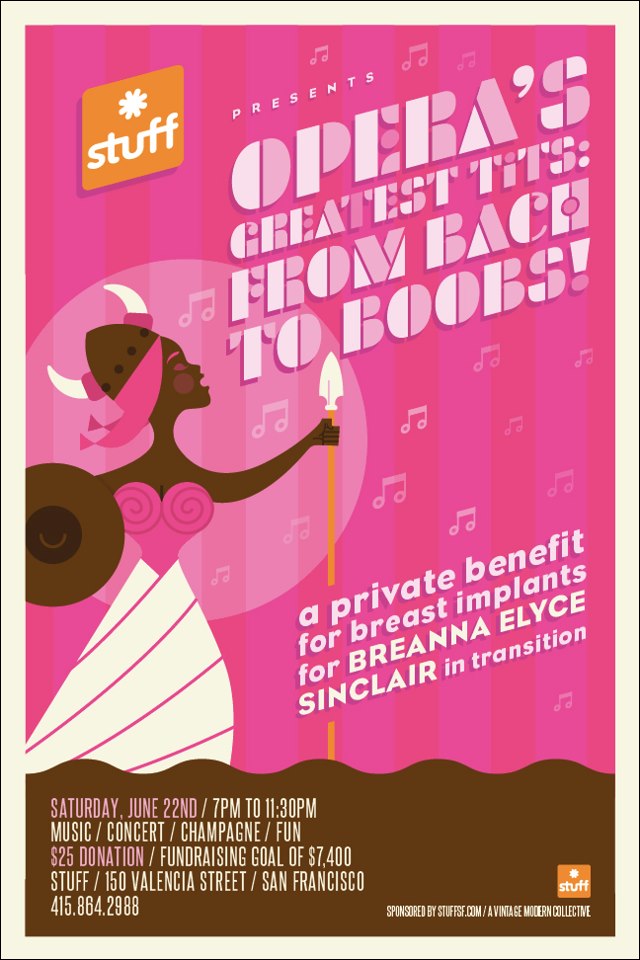

Sinclairé, after a busy school year pursuing her Masters in Music, is currently prepping for the first of several recital-fundraisers designed to help pay for the singer's transition. The first recital, Saturday, June 22nd at the antique store Stuff on Valencia where Sinclairé works, is punningly titled "Opera's Greatest Tits" since, as she laughingly put it: "That's what this recital is paying for! I'll sing Bach to get myself a pair of boobies!" Sinclairé has already performed in works as varied as Mozart's The Magic Flute, Ravel's L'enfant et les sortileges, Rameau's Platee, Gershwin's Porgy and Bess, and Bernstein's West Side Story and is looking forward to getting to use her gifts as a singer to pay for her transition.

The recent Endeavor Scholarship for the Arts recipient is amazingly candid about her life, her journey as a trans woman, and her love of her art form. "I've been to some dark places," she says reflectively, brushing a strand of highlighted hair off her face. "What kept me going inside was knowing I had this gift. When nothing else made sense, I knew I had this voice and that eventually, it would take me places. I hoped it would take me somewhere I could belong."

The Baltimore native knew she could sing at an early age. "In the church I grew up in—and you know how black people are with their church music—I was singing from a very young age," she says, recounting her first experiences as a performer. "I was a really androgynous, feminine child and a lot of times people didn't know if I was a boy or a girl with my big hair and pretty face. I remember standing up there with the choir and just letting go. When they told me I could sing, really sing, it was finally something I knew that was mine."