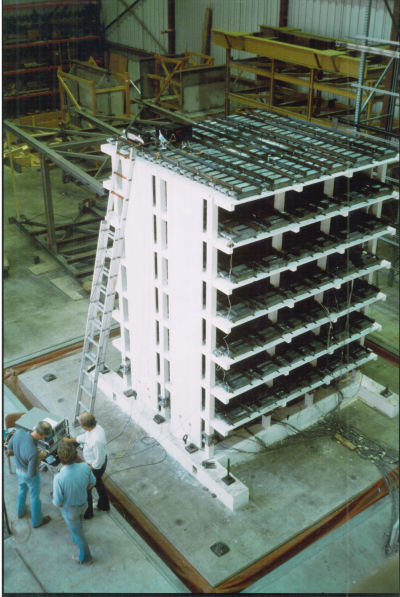

For almost half a decade, engineers have come to the Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research (PEER) Center to better understand how structures respond to the complex and destructive forces of an earthquake. Engineers can’t just wait around for the next earthquake to hit. Instead, they simulate earthquakes on a 20-foot by 20-foot, 100,000-pound, reinforced concrete shaking table.

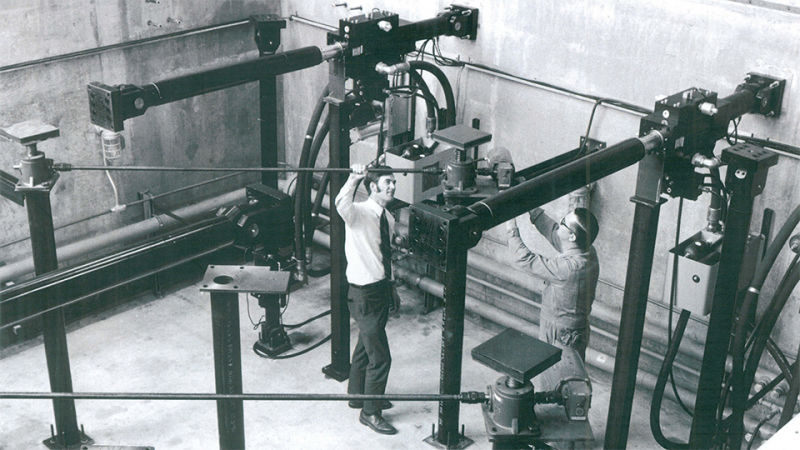

The PEER shaking table is the largest six degree-of-freedom shaking in the United States. What that means is that it can move in six unique directions. It can move horizontally along both the X and Y axes, and vertically along the Z axis. It can also rotate along each of these three axes, allowing for pitch, roll and yaw. Combine these motions together and engineers can simulate just about any earthquake-like movement.

“The simulation of earthquakes is a big part of what we do,” says Khalid Mosalam, Director of PEER. “Putting a structure on the table, we can take a variety of measurements directly on the surface of the table or at different critical points, and that will generate a body of experimental data.”

With this data, engineers can design buildings and bridges that can better withstand earthquakes.

One of the most significant developments to come out of testing on the shaking table is the proof of concept for energy dissipation devices. These devices are placed between the building's foundation and the ground. During an earthquake, the dissipators decouple the ground motion from the building, limiting major damage. Before the 1980s, energy dissipation devices were not readily accepted by the structural engineering profession.