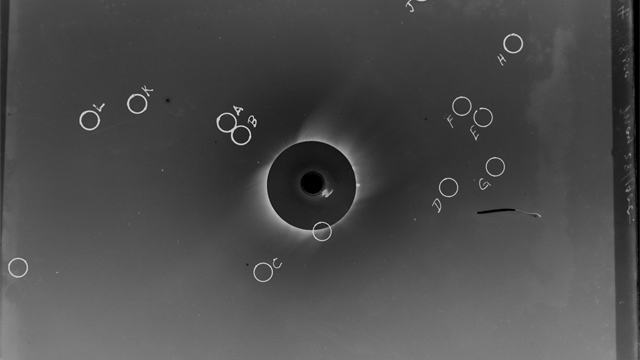

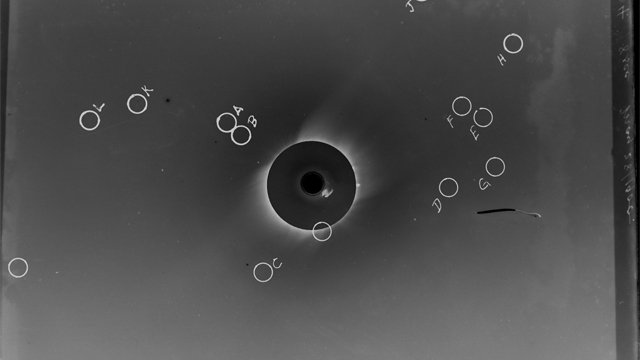

Elevendy-one years ago (that's a hundred and eleven to the non-Shireborne), Chabot Observatory Director Charles Burckhalter set forth on an expedition across the plains of India, risking bandits, tigers, famine, and plague, on a hunt for big game: a rare meeting of the Sun and the migrating Moon in a total solar eclipse. Little could he know, years later his then-world-class astrophotographs of the event would be used in an effort to prove or disprove the General Theory of Relativity published by Albert Einstein in 1916.

Einstein's General Theory of Relativity is the one that describes gravity, that attractive force between objects, not as some kind of invisible bungee cord but as a distortion, or warping, of space (and time) by matter. Other objects within the warped, "curved" space accelerate "downhill" along the curve, toward the mass producing the distortion. Likewise, objects moving through the gravity field are deflected, their trajectories curved toward the mass.

The trick was how to prove this theory with observational evidence. That gravity is a fact is easily demonstrated by holding up an object and then letting go of it. Gravity, whatever gravity is, accelerates it "downward"—in our case, toward the center of Earth's mass.

But how to demonstrate that gravity, as Einstein theorized, is the effect of space-time warped by matter causing objects to slide down the "uneven ground," (yeah, using a lot of quotation marks, I know) was a bit like trying to prove that gnomes are responsible for missing keys (as we all know they are, but just can't prove!)