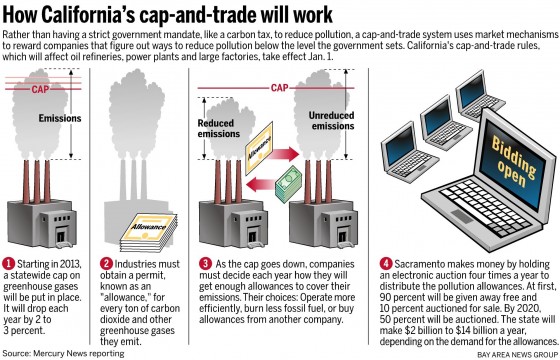

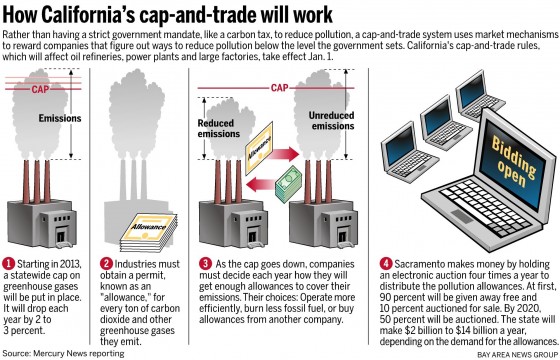

In order to keep up with the lowering emissions cap, businesses have three choices. The first is pretty straightforward: reduce emissions.

The second option is to buy permits to pollute. The state will give companies allowances -- each allowance grants a company permission to emit one ton of carbon dioxide. Companies can buy and sell allowances on the carbon market.

And the third option is known as "carbon offsets." Companies can essentially pay other organizations to reduce greenhouse gases, for instance, by protecting forests. Each offset counts toward the firm's compliance obligation, though companies are limited in how many offsets they can use.

But will it work?

California has been preparing for this moment for a long time. When Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed AB 32, the state’s landmark global warming bill in 2006, he set an ambitious goal: to cut California’s greenhouse gas emissions 30 percent by 2020. Cap-and-trade is supposed to help accomplish a big part of that goal.

"We want to reduce the amount of pollution, but we want to do it in a way that isn’t too costly to the economy," says UC Berkeley economist and energy analyst Severin Borenstein at UC Berkeley. He says the market will create some flexibility for businesses.

But some businesses aren't so sure about it.

"I am very very worried about this program," says Dorothy Rothrock from the California Manufacturers and Technology Association, which represents about 700 companies. Her members are concerned that cap-and-trade will put them at a disadvantage to companies outside of the state.

And Rothrock says the costs will eventually be passed on to consumers. For instance, the price of gas may go up. "It’s not like they’re suddenly gonna see a big bill in their mailbox the next day, but the costs will be coming and there won’t be a lot we can do to stop it," she says.

California has taken steps to minimize this impact. At first, nearly all of the allowances are free for businesses, and some of the proceeds from the carbon market will go to communities hardest hit by pollution. Regulators also argue that the gains in energy efficiency spurred by the program will outweigh any higher costs.

And environmental advocates point out, if we don’t cut emissions now, the impacts of climate change will be even more expensive in the long run.

Emily Reyna with the Environmental Defense Fund says it’s important for California to take the lead.

"If it’s done right here in California, which I believe it will be, then it can be a real model for the rest of the country, the rest of the world," she says.

On Wednesday, all eyes will be on California, when the state's carbon market opens for the first time.