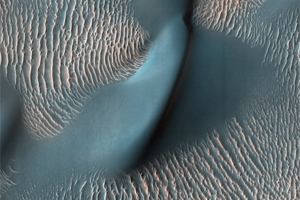

Martian dunes, captured by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance OrbiterWhat started out to be a workaday chore—replacing a broken motor in an exhibit—panned out to be a voyage of discovery to the shifting sands of another world. This is an occupational hazard when working at a place like Chabot Space & Science Center….

Martian dunes, captured by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance OrbiterWhat started out to be a workaday chore—replacing a broken motor in an exhibit—panned out to be a voyage of discovery to the shifting sands of another world. This is an occupational hazard when working at a place like Chabot Space & Science Center….

The motor in question powers a fan in an exhibit built to demonstrate the physical processes of duning—the fluid transport and deposition of solid particulates into collections and patterns. The fan blows up a constant micro-gale within the exhibit enclosure, and visitors get to play Mother Nature by turning a handle and redirecting the wind. Meanwhile, a mass of tiny white glass beads is constantly whipped up into a fair recreation of a sand storm on planet Arakis….

After the chore of installing the new motor, I rewarded myself by enjoying the exhibit a bit. I piled up all of the sand on one side of the tank to see how the fan would redistribute it; I sent the wind from different directions, watching how the freshly blown grains were scattered across the pristine black undersurface; I placed all of the pyrite rocks, which serve as wind obstacles, in one pile. It was a lot of fun.

One thing I noticed that I hadn't paid much attention to in the past was how the dune actually moved, or migrated. Maybe I hadn't watched long enough before, or maybe it was easier to witness because I had stacked the deck by mounding the sand all in one corner, but it was fascinating to see the process.

On the windward side of the giant dune, the scouring wind picked up the sand and carried it racing to the top—slowly peeling away the front face of the dune. As soon as the sand-laden wind reached the crest and took a sudden turn downward, it was slowed a bit, becoming less able to support the sand grains, which then fell out onto the leeward side of the dune in a sandy-wind version of precipitation. The buildup of sand on the lee side eventually formed small avalanches that slid down the face in little dry floods.