“He was a brave man that first ate an oyster.” - satirist Jonathan Swift (1667–1745)

No one knows who that brave soul was who first shucked an oyster, but we do know that by the late 1800s millions of pounds of salty, slimy oyster meat were being harvested from places like North Carolina’s Outer Banks and shipped across the country. The secret was out: raw, steamed, grilled, or fried, oysters were on the menu from coast to coast.

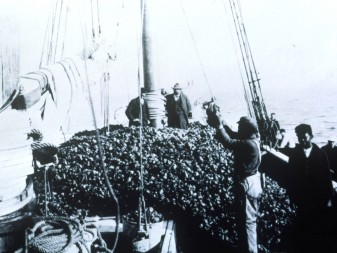

As the demand for oysters increased, fishermen began using more sophisticated tools -- like mechanical dredge boats -- to boost their catch. And boy, were they successful! Marine scientists generally place the current oyster population at around 50 percent of what it was a century ago. And some estimates claim areas like North Carolina’s Pamlico Sound are at 10 percent of the levels that existed in the early 20th century.

One of the reasons that populations have been so decimated and haven’t been able to come back has to do with the habitat needs of the oyster. Baby oysters, or spat, literally grow on the backs of their ancestors. Spat swim in the water column until they can latch on to a suitable surface. More often than not, that surface is an established oyster reef made up of generations of older oysters. As wild oyster harvesting increased, the reefs diminished and baby oysters had no place to anchor. The oyster population plummeted.

But this isn’t just another “species of special concern” story.