QUEST North Carolina’s Daniel Lane contributed to this article.

On a Sunday in February in Eden, North Carolina, a sinkhole formed in the middle of a pond of coal ash slurry next to the retired Dan River Steam Station. A stormwater pipe underneath the ash pond cracked and was sucking in ash and shuttling it to the nearby river. Duke Energy, owner of the facility, sent emergency crews to the site, but it was a complicated fix. By the time they got it securely sealed on Thursday, the 48-inch pipe had belched more than 39,000 tons of coal ash into the Dan.

The Dan, a major tributary of one of the largest and least disturbed ecosystems on the East Coast, ran gray. From Danville, Virginia, whose 42,000 residents draw their water from the river, to Kerr Lake, home to seven recreation areas with 800 miles of trails, a gray ribbon of coal ash was visible along 70 miles of prime sport-fishing territory.

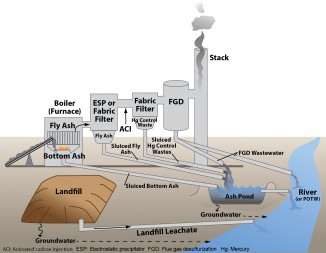

What Is Coal Ash?

Coal ash is a byproduct of burning coal to make electricity. For every nine million tons of coal burned in the U.S., approximately one ton of coal ash is produced. Coal ash is a highly concentrated source of the mineral content that is left after the carbon is burned. It is similar to soil in terms of grain size and texture but contains high concentrations of toxic elements like selenium and arsenic. Coal ash is typically stored wet behind earthen dams adjacent to the power plant. The security of these impoundments is currently under review. The EPA is assessing the hazard potential of the 676 impoundments around the country. As of March 2014, 52 surface impoundments were given a “high” hazard potential rating by the EPA, meaning a failure of the impoundment is “probable, one or more expected.”

Why This Matters

Water tests at the Danville water treatment plant showed a spike in arsenic in the first days of the contamination, but arsenic levels returned to normal a week later. The ash, however, was not gone. It was just gone from view, merged with the most fertile zone in a river -- the nutrient-rich and life-giving layer of sediment.

Most species of aquatic insects live in the sediment, collecting, filtering, and grazing upon minute particles of food. Nothing goes to waste down there, not even the arsenic and selenium from coal ash. Heavy metals get lodged into the tissues of any insect that eats them. When minnows eat the insects, they consume the toxins. Larger fish get toxins from every minnow they eat. As you climb higher in the food chain, the amount of arsenic or selenium you find multiplies progressively. This process is called biomagnification and it has impacts on a food web from bottom to top.