Roy is collaborating with scientists and biotech experts at ten other institutions, including the University of Michigan, the Cleveland Clinic and Case Western Reserve University. Drawing inspiration from Silicon Valley, the researchers have figured out how to take a room-sized dialysis machine and shrink it down to a cartridge the size of a coffee cup.

"What we are motivated to do,” said Roy, “is come up with a solution that will provide the benefits of a healthy kidney to the vast majority of patients that are on dialysis and who have a very low chance of ever getting a transplant kidney."

The researchers have built the prototype of a device that can be implanted in patients and run without batteries or pumps. Their goal: have it in clinical trials in five to seven years.

Healthy kidneys filter toxins from blood. Dialysis machines do the same thing, but require patients to sit, often for three hours or more, several times a week.

The team’s artificial kidney filters blood using strips of silicon, etched with tiny pores. “We're applying state-of-the-art fabrication technologies used in making computer chips to achieve very precise features and dimensions at the nano-scale," said Roy.

By engineering super-thin silicon membranes at the microscopic scale, the scientists have done away with the need for pumps and large amounts of electricity used in traditional dialysis machines. Instead, the patient’s blood pressure is sufficient to pump the blood for filtration through the artificial kidney device.

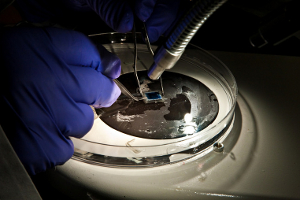

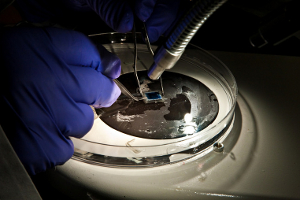

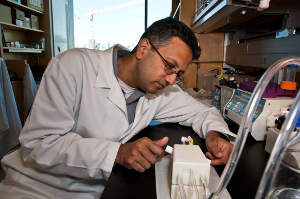

Scientist manipulates pieces of silicon membrane in a petri dish. (Credit: UCSF)

Scientist manipulates pieces of silicon membrane in a petri dish. (Credit: UCSF)

“This is really our contribution,” he said. “Because our silicon membranes don't require a lot of pressure for filtration, we can make them small enough and compact enough to fit inside the little cartridge."

Roy and his team have tested the filtration component of their artificial kidney device on animal models, including rats and pigs. Right now, they’re working to scale it up for use on humans.

According to the National Kidney Foundation, roughly 11 percent of adults in the U.S. suffer from stage one or higher chronic kidney disease, including nearly a million adults in the Bay Area. But most people don’t even know they have kidney disease, which is diagnosed with a simple blood test, until it’s too late.

“Until kidney disease gets to stages four or five, it's a silent disease,” said Patty McCormac, a registered nurse and a program director for the San Francisco office of the National Kidney Foundation.

Patients with End Stage Renal Disease, the last of five stages in chronic kidney disease, when the kidneys have ceased to work, must undergo dialysis. The only alternative is a kidney transplant.

Roughly every five minutes, all of the blood pumped from the heart is sent through the kidneys, which sit below the rib cage on either side of the spine. The five-inch organs filter the blood to remove toxins from drugs, for example, that are ingested and that build up from the daily metabolic activity of the liver and the muscles in the body.

They also perform the crucial job of balancing water, salts, minerals and acid in the blood through hormones and other chemical messages which are relayed from other parts of the body to let the kidneys know whether to increase or decrease the amount of water, mineral salts or acid in the blood. Kidneys also help regulate blood pressure and spur the production of red blood cells.

Some Bay Area kidney patients already are watching Roy’s research with the hope that one day it could change their lives.

David Anderson is a 60 year-old San Francisco resident who first started dialysis 11 years ago. After a four year wait, he received a kidney transplant in 2003, but the kidney failed in 2007. So he had to resume visits to the dialysis outpatient clinic at UCSF Mount Zion.

Anderson found out about Roy’s research in August while talking with a friend of his who had read about it on the internet.

“The potential that this artificial kidney might be available in five years has changed my outlook,” he said. “It has given me a more disciplined participation in my own treatment -- a discipline with my diet, which is more likely to keep me around for those five years.”

Although Anderson tolerates dialysis fairly well, many patients can experience fatigue, nausea and low blood pressure after the treatment. When Anderson started dialysis, he also suffered from hypertension, which along with diabetes, causes two-thirds of all cases of chronic kidney disease.

According to the U.S. Renal Data System, roughly 350,000 adults in the U.S. were on dialysis in 2007, including nearly 50,000 adults in California alone.

Dialysis is also expensive. In 2007, Medicare spent on average more than $72,000 per patient on dialysis treatments. The cost of the artificial kidney, Roy said, would be comparable to two years of dialysis treatments and cheaper in the long run as expensive immunosuppressant drugs would not be needed to maintain it.

If the researchers are successful, dialysis patients would experience a greatly enhanced level of mobility and independence.

“It would potentially be like having your own little artificial kidney, so you'd be able to get up and walk around. It would revolutionize treatment. The dialysis machines we use today, you're basically sitting in a chair for four hours at a time,” said Dr. Lynda Frassetto, a kidney doctor and professor of medicine at UCSF. “We don't let you get up.”

By using the tools of nanotechnology, some of which were developed at UC Berkeley, Roy and his team are able to cut shapes and precise patterns into silicon, much like electrical engineers do in designing a computer chip to carry out complex calculations and tasks.

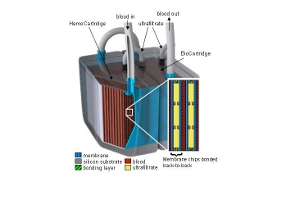

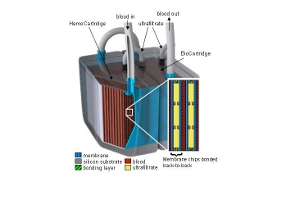

But here the silicon is tailored to be the right size and shape for blood filtration, so tiny pores - a few billionths of a meter in size - are cut into silicon wafers, the same material from which computer chips are made. The silicon wafers are then cut into strips and assembled into rows which act as filters, the first stage of Roy’s artificial kidney.

Much like a real human kidney, the silicon filters take a portion of the patient’s blood and remove toxins from it, along with sugars, water and salts. The portion of the blood that is unfiltered returns to the body, eventually cycling back for filtration.

The filtered blood, or “filtrate”, then passes to a second compartment, the bioreactor, for additional processing. In the bioreactor, the filtrate passes over a bed of kidney cells, which could be cultured from the patient’s own kidneys or they could come from a donor.

“As the filtrate flows over this bed of cells, the bed of cells senses how much salts and sugars the body needs and they reabsorb the salts, sugars and much of the water back into the body”, said Roy.

Schematic image of the artificial implantable kidney device being developed at UCSF. Click here for a larger image. (Credit: Dr. Shuvo Roy, UCSF)

Schematic image of the artificial implantable kidney device being developed at UCSF. Click here for a larger image. (Credit: Dr. Shuvo Roy, UCSF)

So the bed of kidney cells would help perform a job that the most advanced dialysis machine currently can’t do: maintain the critical balance between water, salts and other constituents of blood, which healthy kidneys do automatically.

And even though the kidney cells may not come from the patient, they wouldn’t be rejected by the patient’s immune system - a problem that until now, has inhibited the development of an artificial, implantable kidney. This is because the silicon membrane on which they sit contains pores that are big enough to allow the filtered blood through where it mingles with the live kidney cells, but they’re too small for the body’s immune cells to pass through and attack them.

“So if they can use this artificial kidney filter and they don’t need to give people anti-rejection medication, that's huge,” said Frassetto.

UCSF Bioengineer Shuvo Roy works on a model of an artificial, implantable kidney. (Credit: UCSF)

UCSF Bioengineer Shuvo Roy works on a model of an artificial, implantable kidney. (Credit: UCSF)