Right now, the industry mostly consists of video games. They cost anywhere from 50 to 400 dollars. They're also popular thank you gifts for public media station fund drives, including KQED. Examples include Lumosity, Cognifit, and Happy Neuron.

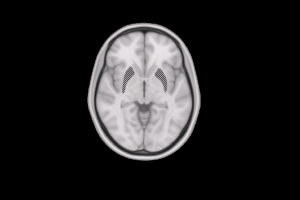

One game, made by the San Francisco-based company Posit Science, involves listening carefully to short blasts of sound, and determining whether the pitch goes up or down. The general idea is that by doing a series of basic and repetitive tasks, which get harder over time, you’re actually changing your brain structure. Over time, the manufacturers claim, you can train an old brain to behave like a new one.

“All of the physical, functional, and chemical functions that contrast the old versus young brain -- and I mean all -- appear to be reversible,” says Mike Merzenich, the Chief Scientific Officer of Posit Science and a retired professor of neuroscience at UCSF.

But many scientists who study aging are skeptical.

“I think most of the claims they make are exaggerated,” says Murali Doraiswamy , who teaches psychiatry and geriatrics at Duke University Medical Center, and has researched these games.

Doraiswamy is not entirely critical of brain fitness games; in fact, he believes some of the research on them is promising. But he says there hasn’t been nearly enough of it.

“Because they can sell these products without FDA approval,” he said, “there’s not a lot of incentive to do the kinds of large clinical trials. And unfortunately because of that, the evidence is still weak.”

Take, for example, an issue scientists call "transfer."

Say you start getting higher scores on a brain fitness game. Is that all that's changed? Several game manufacturers have studied this, and the manufacturers say the skills do carry over to the rest of your life.

Laura Carstensen, who directs the Center for Longevity at Stanford University, disagrees. “It's the difference between I can teach you something, or I can make you smarter.”

“Can you improve your brain so that it's faster, more adept, more vital? That's what the claims are, and I don’t think there’s really any evidence for that.”

There is one thing, however, that Carstensen and other aging experts say can stave off the effects of aging on the brain: exercise.

“I think that the research such far demonstrates a much clearer link between exercise and brain health,” says Joel Kramer, a neuropsychologist at UCSF's Memory and Aging Center.

When asked his advice on how to improve brain functioning, Kramer’s advice was simple: “Head to the gym and start getting some aerobic exercise.”

Of course, it isn’t just the fear of normal aging that has people buying brain fitness programs.

In his office, Kramer showed me a video of a medical screening he’d done on a patent. Kramer read the man a list of words, and then, seconds later, asked the patient to repeat them. “Can’t remember a single one,” said the patient.

This is not normal aging. This is Alzheimer’s disease. Asked whether brain fitness programs could have helped Joel Kramer’s patient, Stanford's Laura Carstensen was unequivocal. “No evidence. No evidence. None. Zero. That these games could prevent Alzheimer’s disease.”

At this point, nothing has been shown to prevent Alzheimer's. Not crossword puzzles, not Sudoku, not exercise. But that doesn’t mean Carstensen won't give advice to people who worry about becoming forgetful as they age:

“Continue to be involved in the community, with kids, with schools, with work.”

Studies have shown that in addition to exercise people who do things like teach kids to read, or take dancing lessons, seem to stay sharp, longer. Scientists aren't sure why that is, exactly, but they say it’s not a bad program to follow.

Says Duke’s Murali Doriswamy, “my recommendation is whatever it is that they find novel, they find challenging, and to stick with it.”

Listen to When Brains Hit the Gym radio report online.

Listen to When Brains Hit the Gym radio report online.

37.76355 -122.458

There is one thing that aging experts say can stave off the effects of aging on the brain: exercise.

There is one thing that aging experts say can stave off the effects of aging on the brain: exercise.