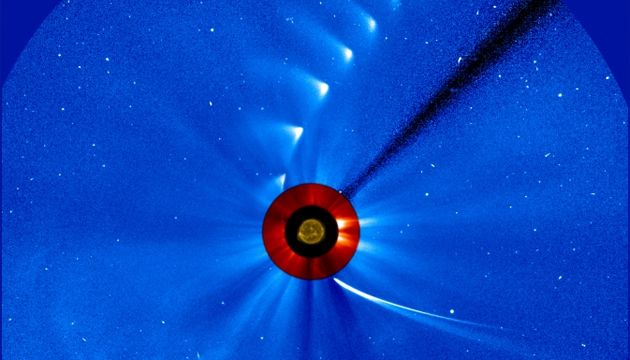

An array of Earth-and space-based telescopes (plus Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter out at Mars, ISON’s first port of call in the inner solar system) were able to observe ISON from when it was still more or less a pristine frozen nucleus of primordial ices left over from the solar system’s formation all the way to a very close perihelion. Along the way, ISON surprised us with sudden, unexpected outbursts of gas, and finally a complete breakup, all caught on video by the European SOHO and NASA’s STEREO spacecraft.

It must have been an incredible sight. Can you imagine a mountain-sized ball of ice completely breaking up and vaporizing in only a few days’ time? If Hollywood were to make this dramatic breakup into a movie, they probably could not go over the top with special effects.

Though there may be little to nothing left of ISON to latch our eyes and telescopes onto, ISON’s departure hasn’t left us with empty skies.

Another comet, C/2013 R1 Lovejoy, has been quietly shadowing its media-hog cousin ISON. Discovered only in September Lovejoy has already made its closest approach to Earth, back on November 19th, but has yet to reach perihelion, which takes place on December 22nd.

Whereas ISON’s perihelion on Thanksgiving was a harrowing 730,000 miles from the sun’s surface (less than one solar diameter), Lovejoy’s is a more sober 75 million miles—not even within Venus’ orbit. At this distance Lovejoy isn’t in any danger of breaking up or being vaporized, but also isn’t enjoying as much sunlight or media attention as ISON did.

In a way, Lovejoy is the mythical Daedalus to ISON’s Icarus. In the Greek myth, Daedalus was a master craftsman, and along with his son, Icarus, was imprisoned on Crete by King Minos. Daedalus constructed two sets of wings from feathers and wax for himself and Icarus so that they could escape (think Iron Man and hang-gliders.) Daedalus cautioned his son not to fly too close to the sun, but Icarus, giddy with the ability to fly, ignored the advice. The sun melted his wings and he plummeted into the sea and drowned. The wiser and more level headed Daedalus kept his distance from the sun and flew a safe course to freedom.

Speaking of sun-grazing comets and mythical flying figures, there is a sun-grazer of a third variety making its presence known this month: 3200 Phaethon—a “rock comet.”

In Greek myth, Phaethon was the son of the sun god, Helios. Wanting recognition as the son of a deity, Phaethon was given the keys to his dad’s chariot, but ended up driving so recklessly that he put the entire Earth in peril—so dad was forced to end the joy ride with a thunderbolt.

3200 Phaethon is a sun-grazing asteroid that produces outbursts of dust as it orbits, leaving behind a trail of dust much as a comet does. Exactly how it sheds dust particles isn’t clearly understood, but may have something to do with the solar heating of hydrated minerals that outgas water vapor and carry dust with it.

When Earth passes through 3200 Phaeton’s dust trail, which it is currently doing, we enjoy the annual Geminid meteor shower, which reaches a peak in meteor activity on December 13/14 this year. Ordinarily we associate meteor showers with Earth’s passage through the dust trails of comets, so the Geminid shower has added value as originating from a mysterious object that blurs the distinction between comets and asteroids.

The good news is, unlike Phaeton the reckless teen of myth, Phaeton the rock-comet poses no danger to the Earth.