“Not too little, too late, but…helpful. But not enough,” is the way he described the month of March following a symposium on — ironically enough — extreme precipitation.

Anderson says there’s a temperature sweet spot for winter storms that deliver snow with the highest water content, which is really what matters. Too cold and the storm can’t hold sufficient water vapor, too warm and the snow line (the elevation where rain turns to snow) gets pushed higher up the hill, causing more precipitation to fall as rain.

“With the warmer storms and the higher-elevation snow lines, you don’t have enough time with the cold air to build that pack,” Anderson explains. This winter, he says, we just didn’t hit the sweet spot often enough.

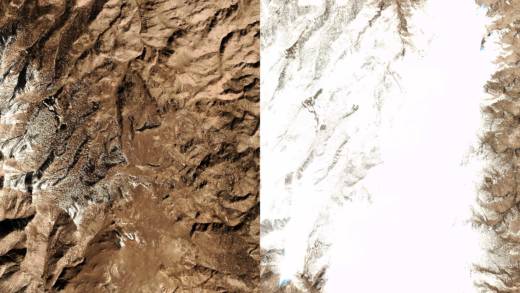

Even this year’s disappointing pack beats by a long shot the same date in 2015, when the snowpack clocked in at 5 percent of normal.

Monday’s official survey of the snowpack is significant, as April 1 is considered the peak of the snow season, before accumulated snows begin to melt and become runoff.

“We’ve seen the bulk of our precipitation,” Anderson says, pointing out that 90 percent of a typical year’s precipitation falls between October 1 and April 1.

The Sierra snowpack provides about a third of California’s water supply. Last year’s abundant rain and snow left many of the state’s largest reservoirs brimming. That “carryover” should stave off another drought emergency this summer, but it means Californians will count that much more heavily on next year’s wet season.

“It’s really that look ahead of, ‘What does next year bring,'” says Anderson, “and this kind of year brings that to the forefront.”