How come?

Take a city like Palmdale, where water use rose 5 percent after the drought was called off compared to the same period in 2016. Palmdale allowed people to water their lawns more often, and backed off on enforcement.

“We wanted to maintain credibility with our customers,” said Dennis LaMoreaux, the general manager of the Palmdale Water District. “And if the state says the drought is over, and if customers don’t see a change in the rules, that kind of undermines the credibility of next time we really need them to save water.”

Other cities, like Redlands, didn’t change any of its water rules, but officials suspect their customers started to slack off because they’re hearing mixed messages about the need to conserve. Water use during the six months following the end of the drought was up 18 percent compared to the same period in 2016.

“We made the point to them that even though the state has declared the drought over, all the restrictions remain in place for Redlands customers,” said Cecilia Grado, a water resources specialist with the city of Redlands.

But, she added, “We can’t compete with the media.”

What does the media have to do with it?

Media coverage of drought may be critically important in encouraging conservation, according to a 2017 study in Science Advances. Researchers at Stanford University surveyed nine daily newspapers during two droughts, looking for stories having to do with “California drought,” “water conservation” and similar terms. The first drought occurred during the Great Recession and received relatively little media coverage, where as during the second, beginning in 2012, media coverage was “extraordinarily high.” They found that over a two-month period, an increase in 100 drought-related articles was associated with an 11 to 18 percent reduction in water use.

But the media coverage wasn’t happening in a vacuum – reporters were covering changes in rules and regulations.

“Political action was being broadcast by the media,” said Newsha Ajami, the head of Urban Water Policy at Stanford University, who co-authored the study. “And then that was impacting people’s behavior. And that was feeding back into more political action, and more media coverage.”

But since Brown called off the drought, media coverage has also dried up.

“Water issues in California have fallen off that priority list,” she said.

Should we all still be cutting back on water?

For Ajami, that depends on what we’re doing with the water we’re using.

“If people were collecting shower water to flush their toilets, I think they should take a break,” she said. “But if we’re using more water outdoors because we want to have lush lawns and green spaces, then that’s not OK. If we’re washing our cars, that’s not OK. We need to be mindful of the fact that this water comes to us through a lot of effort, and also, it’s not an infinite resource.”

For Jelena Hartman, a senior scientist at the State Water Resources Control Board, the main challenge is to get Californians to switch from an emergency conservation mindset, with shower buckets and dead grass, into a long-term, water-saving way of life.

That means replacing lawns with artificial turf or native plants, fixing leaks, ripping out old toilets and washing machines and putting in more efficient ones instead.

“As a state there is a lot of work to be done to move away from those short-term emergency conservation measures to something that can be a permanent change,” she said.

How can we save water in the long-term?

At the state level, the Water Resources Control Board is working on a proposal to permanently ban wasteful uses of water like watering your lawn until it runs into the street, washing a car without a shut-off nozzle and irrigating street medians.

There are also two bills in the state legislature, AB 1668 and SB 606, that would clamp down on water use in cities by forcing them to use water more wisely. The bills would set a limit of 55 gallons per person, per day, for indoor use.

But outdoor use is by far the bigger problem. More than half of all the water used in cities in California is sprinkled on lawns, flowers and ornamental trees. So the two bills would set limits on how much you can use depending on where you live. Cooler, denser cities with smaller lots and multi-family homes, like San Francisco and Santa Monica, would be required to use less water than hotter, more suburban cities with larger homes and yards like Riverside and Redlands. The State Water Board would slowly begin ratcheting up enforcement, with no fines until after the first five years of the program.

What about in my city?

Some cities are still doing a lot too! Places like Los Angeles and Redlands never let up on the rules and regulations they had during the drought. Others, like Santa Monica, are passing new, even more ambitious ordinances to keep water use low. Santa Monica’s new water neutrality ordinance, passed three months after Gov. Brown declared the drought over, requires new developments to use the same amount of water as the building they are replacing.

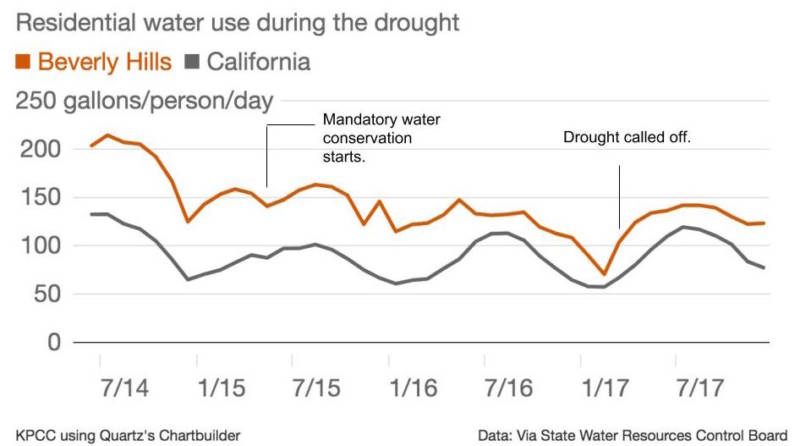

Others cities are phasing in “smart meters” that read water use data in real time and allow city staff to quickly detect leaks. In Beverly Hills, water conservation manager Debby Figoni gets a list every day of the biggest water users in the city.

Looking at graphs of their water use, she can tell if they’ve got “continuous flow issues” like leaky pipes, a broken sprinkler or a running toilet. When she calls residents to tell them about the leak, she offers them a rebate on their bill for fixing it – but only if they agree to reduce outdoor water use first.

“So now, I’ve had this opportunity because of this issue to also educate them on efficient irrigation,” she said. “And that’s very important.”

While some cities, like Los Angeles, are still offering rebates to remove grass lawns, the largest source of additional rebates, the Metropolitan Water District, has dried up. The agency is voting in April whether to resume the program. However, MWD does still offers rebates on low-flow toilets, high-efficiency washers and irrigation controllers. It may boost the amount of those incentives to encourage people to switch them out.

This story is part of Elemental: Covering Sustainability, a new multimedia collaboration between Cronkite News, Arizona PBS, KJZZ, KPCC, Rocky Mountain PBS and PBS SoCal.