This story was originally published in January 2019. It is being republished after a magnitude 4.3 earthquake centered near Berkeley rattled the Bay Area on Monday morning. Read more here.

On two straight mornings in January 2019, residents awoke to the familiar rock and roll from a cluster of relatively small earthquakes along the Hayward Fault, across the bay from San Francisco. It’s not the first time, nor will it be the last.

While neither the magnitude 3.4 nor 3.5 quakes broke the seismograph, the two events struck in essentially the same spot. Both had epicenters nestled in the Oakland-Berkeley Hills, just a few miles from the UC Berkeley campus.

Such cluster quakes always get people wondering if they mean more than the usual random jiggling. To get a read on this, we spoke to earthquake experts with UC Berkeley’s Seismology Lab about what it means, if anything, when it comes to forecasting the next Big One.

According to Peggy Hellweg with UC Berkeley’s Seismology Lab, there’s minor earthquake activity occurring almost continuously along the Hayward Fault, though most of it goes unnoticed.

And while January’s “felt quakes” were reported as individual events, they can be thought of as belonging to the same sequence of earthquakes.

“I would actually group them together since they’re so close together on the fault and call one the foreshock, and then the one from Thursday morning, the main shock,” Hellweg says.

What Kind of Fault?

The trouble with terms like “foreshock” and “aftershock” is that scientists never know how to categorize one or the other until after the shaking settles down.

Hellweg says she wouldn’t have been surprised to see tiny quakes or even another of similar size in the days following to finish out the sequence.

“If you look at the history of earthquakes along this section of the Hayward Fault, there can be from one to four earthquakes felt by the people who live here,” Hellweg says.

What do minor “felt quakes” foretell about the likelihood of the next Big One hitting the Hayward Fault?

Short answer: There’s no way to know for sure.

On the one hand, Hellweg says, in the last 20 to 30 years, “no big earthquake has happened on the Hayward Fault associated with one of these little sequences of earthquakes.”

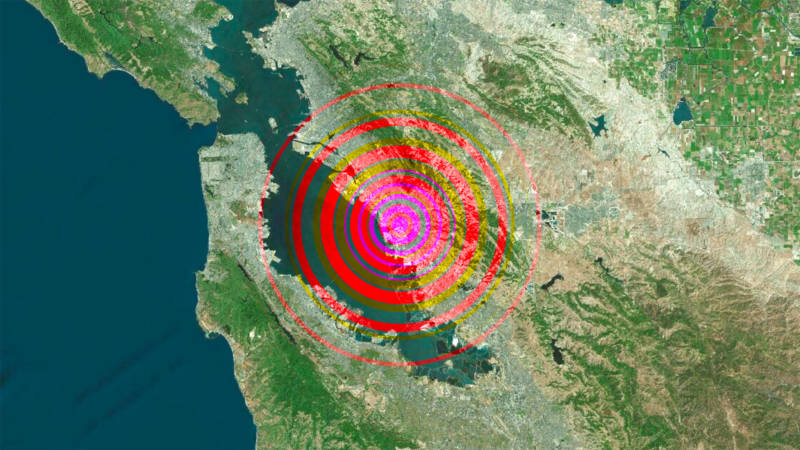

But here’s the bad news: pressure has been building up on the Hayward Fault. It’s been more than 150 years since the last major earthquake to rattle the fault, which stretches through the most densely populated stretch of the East Bay.

Geological studies put the average interval between big quakes on the Hayward Fault at about 140 years, give or take 50 years. Meaning the Big One could happen any day now or not in the lifetime of many middle-aged residents. Scientists who developed the HayWired modeling scenario estimate that there’s about a one-in-three chance of a magnitude-7 quake on the Hayward within the next 30 years.

And here’s the other bad news: the oft-repeated idea that minor temblors serve to relieve pressure on the fault and lessen the chances of a major event, is a myth.

On the question of whether it happens tomorrow, Hellweg says, “Do I expect it? No. Would I be surprised? No.”