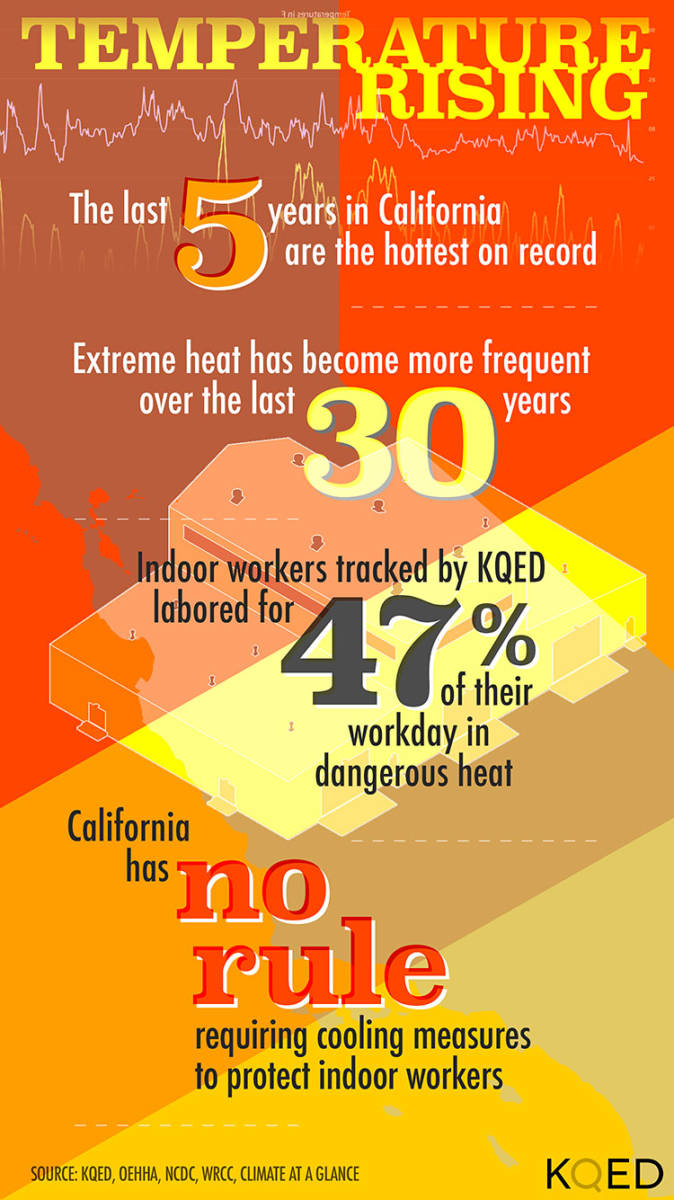

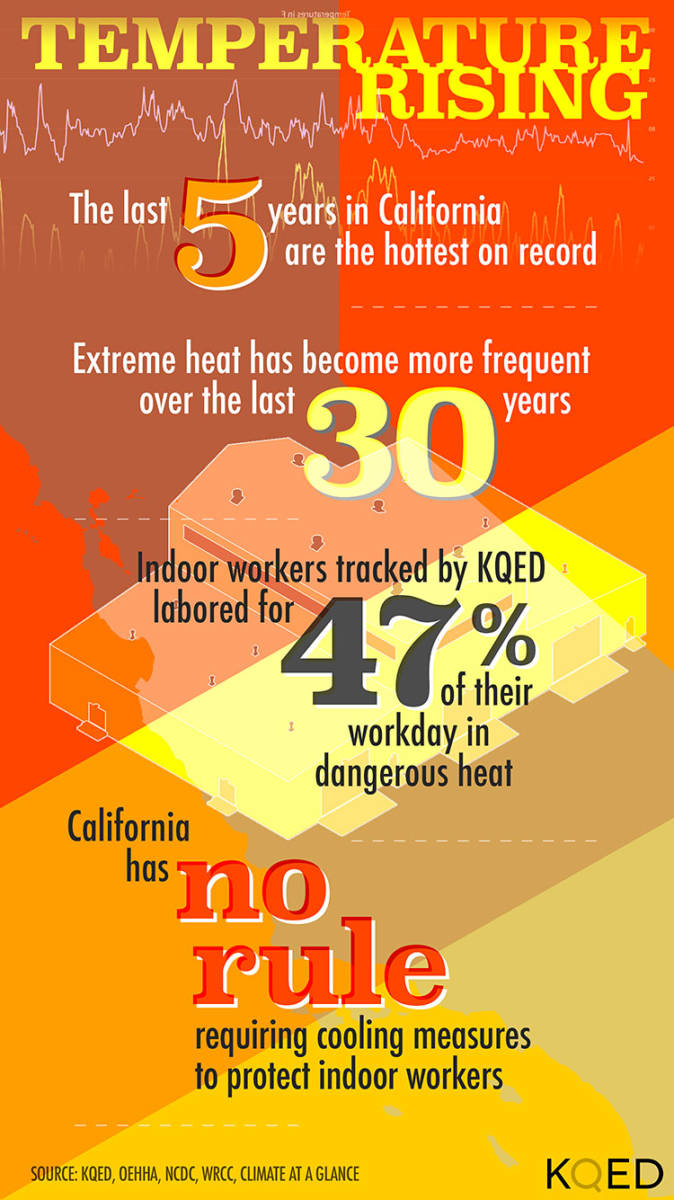

For Brandon, heat’s already a real threat. Last year, when at the request of KQED he wore a sensor to work during July and August, he experienced heat above 90 degrees about 40% of the time, enough to make him sick.

“I felt bad twice a week, I got headaches,” he said.

It doesn’t help that Brandon has high blood pressure, a condition that makes it harder to sweat. Other chronic conditions people have also make sweating more difficult: asthma, heart and lung problems. So do some medications taken for those illnesses. Brandon himself takes a pill each morning for hypertension.

When it’s really bad, his company will give out bottles of water, he says. When the temperature spiked above 100 degrees last month, the company offered workers gum; Brandon’s head was aching, so he asked for aspirin.

Employers are supposed to protect workers’ health and safety. But no federal rules limit heat indoors. There are no regulations, yet, in California either — no required rest breaks, water, or places to cool down.

Employers only have to report the very worst cases of heat sickness, when someone dies or goes to the hospital for more than a day.

Health researchers and workers like Brandon say falling ill from the heat is a lot more common, and more punishing, than the numbers show.

“The heat is ugly,” Brandon says. “It’s an inferno. It’s like hell. The people that are cool work inside the offices. But us, we work with the devil.”

State lawmakers agree it’s too hot. Three years ago, the governor signed a law that requires the Division of Occupational Safety and Health to make a rule protecting workers from indoor heat. Under a proposal circulating now, if it’s not feasible to prevent hot conditions, employers have to limit workers’ exposure or offer them protective cooling gear to wear on the job.

The rule was due in January, but state regulators may not finish it until next year.

All employees are covered by worker’s compensation insurance, according to Dr. Robert Harrison, who founded UC San Francisco’s occupational health clinic and formerly served on the state’s Occupational Safety & Health Standards Board. That means if workers get heat-sick, they can report their illness and go to a health care provider.

In practice, though, workers fear that if they get sick on the job, the boss might see them as a problem.

Last October, Brandon had made it through most of the day, driving his forklift in and out of steel containers, moving pallets of electronics and boxes of kitchen goods. But he recognized that familiar feeling of heat building up in his body, and he knew he would soon be sick.

He asked if he could leave to see his doctor. But a manager said no, the company’s policy was to call an ambulance.

That’s a situation workers often try to avoid.

An Expensive Ambulance Ride

Ambulance trips like the one offered Brandon can cost workers money.

Doctors underdiagnose heat sickness. When workers report symptoms like headaches and nausea, a doctor might pin them on a pre-existing condition, with no linkage to heat. As a result, the diagnosis code might indicate an old ailment had simply flared up.

An emergency room doctor blamed Brandon’s symptoms on hypertension. That ER visit cost him $300, and his health insurance didn’t cover the rest of the bill: $3,000 more.

An emergency room doctor blamed Brandon’s symptoms on hypertension. That ER visit cost him $300, and his health insurance didn’t cover the rest of the bill: $3,000 more.

Brandon says he talked with his employers about the bill, and he asked them to cover it. “It wasn’t my idea [to go to the ER], I was going to go to my doctor,” he said.

They turned him down.

As of now, he hasn’t filed for worker’s compensation. From Brandon’s perspective, it’s a gamble. Insurers might deny his claim that heat sickness was a work-related injury, especially because the paperwork attributes it to a pre-existing condition. So he might not get paid. Meanwhile, he worries that the claim itself would put a target on his back, identifying him as a troublemaker with the bosses.

Pledging Allegiance, Feeling the Heat

The business of moving goods through the Inland Empire keeps growing.

Almost a century ago, this area was famous for oranges. Chinese, Japanese and Mexican workers earned pennies and breathed oily smoke from fires that kept the trees from freezing. During World War II, the Kaiser steel plant in Fontana where Brandon lives, employed thousands of union workers. It closed in the 1980s.

Nowadays the Inland Empire is rich in warehouse jobs. But they’re almost all nonunion.

Last year, the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles together were the nation’s busiest; most of their cargo heads to Riverside and San Bernardino counties. On average, the region adds about a football field’s worth of warehouse space a day.

Jobs grow fast, here, too. Eighty-five thousand men and women now work in warehouses in the Inland Empire — mostly Latino, like Brandon. Some make as little as $12 an hour.

Brandon says his company can always find someone to take his place.

“What can we do?” he says. “They tell us: ‘If you don’t like it here, there’s the door, you can walk out.’ ”

Low-wage and immigrant workers say they fear retaliation. When they complain about heat, when they get sick, when they ask for aspirin, and definitely when they file for worker’s compensation.

A small American flag is clipped to the wall in Brandon’s kitchen, above the microwave. He’s a U.S. citizen; his naturalization ceremony was last year. For a long time he hoped pledging allegiance might help him get better conditions at work. He doesn’t think that anymore.

“If there are people who were born here, people who, because they were born here, know all their rights, maybe someone can listen to them,” he says. “If I put myself next to that person, they will listen more to him than to me. A hundred percent.”

Brandon stands well over 6 feet, and during heat season, he loses weight. What’s left is muscle — he’s a bear of a man.

“You might see me like a bear, but there, they ignore you, they make you smaller than you are, they don’t pay attention,” Brandon says.

Driving a forklift pays Brandon around $18 an hour, just about a living wage in this region. The warehouse was sold last year, and the new owners cut his salary a buck.

“How long have I been working in the warehouse? Years. How long have I been in this country? Years. And it’s always the same.”

Brandon has also worked as a warehouse lumper, moving boxes by hand. He’s been a mover and worked in manufacturing. He knows heavy labor. He came to California from Michoacán, in Mexico, so he knows hot weather. Familiarity with heat and work isn’t enough. There are limits to how fast the human body can acclimate.

Even before people reach those limits, these conditions make work more dangerous. Heat makes people irritable. It causes more mistakes and accidents.

The best insulation against heat is money. Money can buy air conditioning, or medical care. But as heat intensifies, that protection starts to thin.

“The heat is not asking people for their papers,” says Brandon. “The heat reaches everyone the same. Do you hear me? The heat is fucking us all over.”

Brandon says nobody has to tell workers when heat becomes unsafe. They’ve been trying to tell anyone who would listen.

“Look at the climate,” he says. “It’s changing, it’s getting hotter. But what are they doing about it? The people at the top, the people in charge, they’re not looking for a solution for us.”

An emergency room doctor blamed Brandon’s symptoms on hypertension. That ER visit cost him $300, and his health insurance didn’t cover the rest of the bill: $3,000 more.

An emergency room doctor blamed Brandon’s symptoms on hypertension. That ER visit cost him $300, and his health insurance didn’t cover the rest of the bill: $3,000 more.