There are enormous costs to doing nothing.

Beyond threats to public health and the environment, climate change poses a danger to the economy, especially for those who have the least.

Those are the findings of a new analysis from the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research and the Hamilton Project, a centrist economic think tank of the Brookings Institution.

Two factors will determine just how disruptive climate change will be, according to the study. One is the extent of the warming; the other is the effectiveness of any mitigating technology and policy.

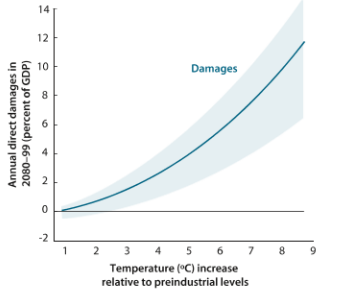

By the end of the century, an increase in temperature of 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels could trim .5% off of U.S. gross domestic product, the economists found. At 4 degrees of warming the decline would hit 2%.

From there, the damage would increase exponentially as warming continues.

The U.S. counties with the weakest economies, will be hit hardest, the report says. Similarly, around the world, the countries with the lowest incomes will face the most hardship.

Lower Emissions But Economic Growth

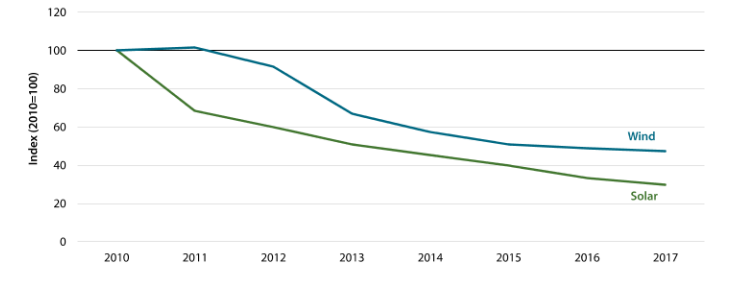

The researchers point out that lower emissions and economic growth are not mutually exclusive. Between 2007 and 2017, U.S. planet-warming gas emissions dropped by 14%, while economic output grew 16%. Energy use fell, as did the price of developing renewable energy sources, especially solar and wind. (U.S. emissions rose again in 2018.)

“Economic impacts from climate change unmitigated would be very, very large,” said Jay Shambough, a study author and former member of the White House Council of Economic Advisers. But there are clearly things that can be done. We’ve been making progress. Not enough, but some.

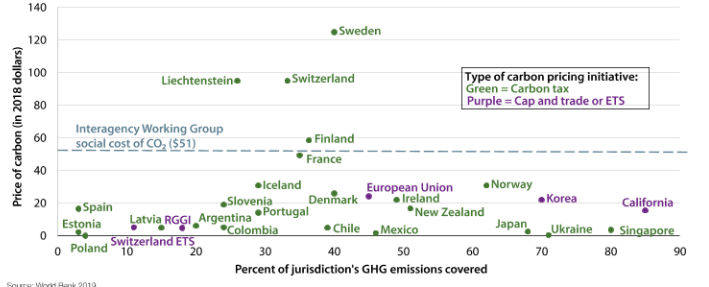

“The important thing for us is to be clear that different policy approaches have different costs and benefits. Some ways to reduce carbon emissions can be pretty expensive, while other ways are more flexible and not actually that expensive.”

The study estimates the average cost of a host of climate policies; the researchers found that replanting forests and flaring methane gas are on the less-expensive end, along with the regulation of emissions from power plants and cars in former President Obama’s Clean Power Plan. The Trump administration replaced those regulations with significantly weaker rules that could end up increasing emissions.

More expensive climate solutions include weatherization assistance and vehicle trade-in programs like “Cash-for-Clunkers,” although these offer benefits beyond carbon reductions.