Since then, spread of the virus in China has slowed to a trickle; the country reported only 19 cases on Monday. And South Korea, which has had the third largest outbreak outside of China, also appears to be beating back transmission through aggressive actions. But other places, notably Italy and Iran, are struggling.

For weeks, a debate has raged about whether the virus could be “contained” — an approach the WHO has been exhorting countries to focus on — or whether it made more sense to simply try to lessen the virus’ blow, an approach known as “mitigation.”

That argument has been counterproductive, Mike Ryan, the head of the WHO’s health emergencies program, said Monday.

“I think we’ve had this unfortunate emergence of camps around the containment camp, the mitigation camp — different groups presenting and championing their view of the world. And frankly speaking, it’s not helpful,” Ryan told reporters.

Caitlin Rivers, an assistant professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, said any lessening of spread will help health systems remain functional.

“Even if we are not headed to zero transmission, any cases that we can prevent and any transmission that we can avoid are going to have enormous impact,” she said. “Not only on the individuals who end up not getting sick but all of the people that they would have ended up infecting. … And so the more that we can minimize it, the better.”

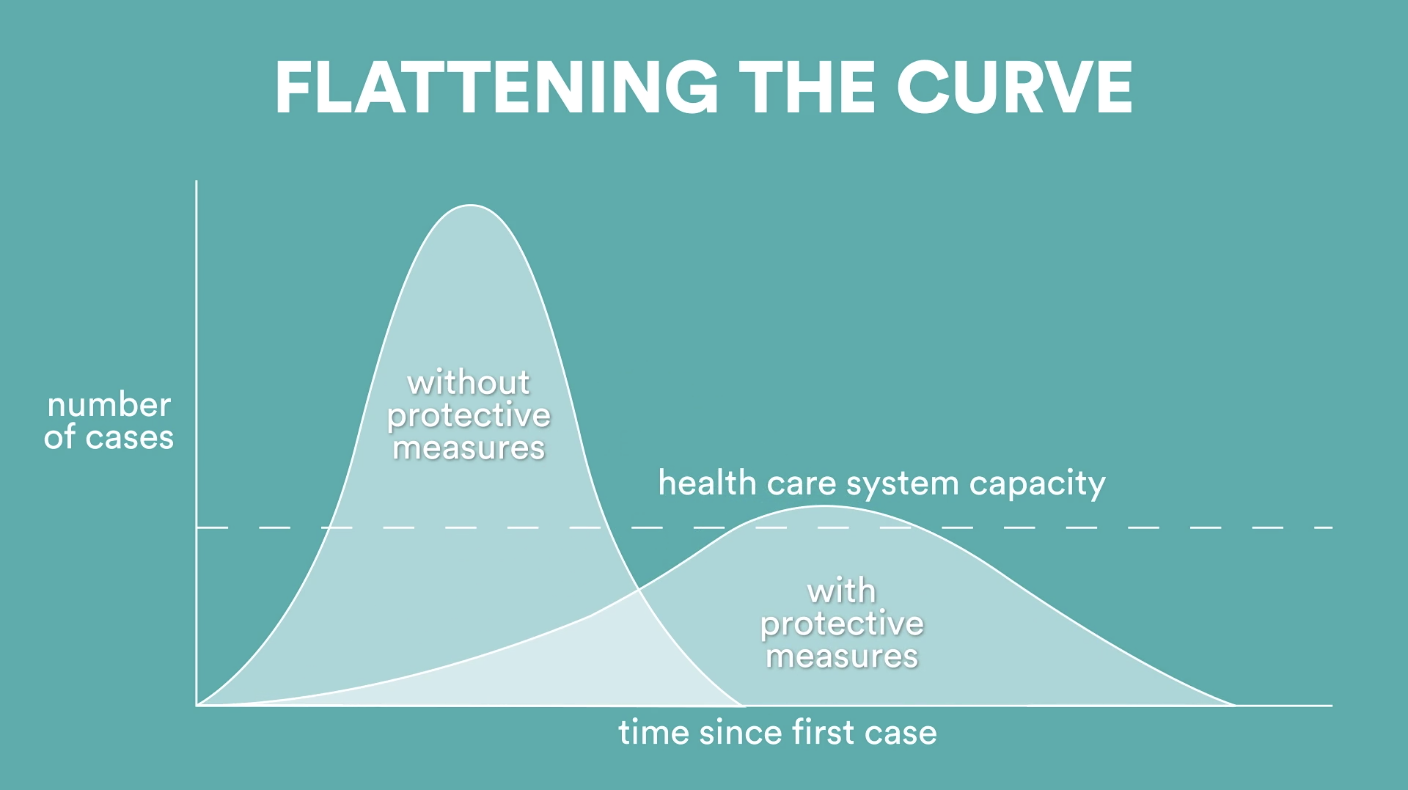

On any normal day, health systems in the United States typically run close to capacity. If a hospital is overwhelmed by COVID-19 cases, patients will have a lower chance of surviving than they would if they became ill when the hospital’s patient load was more manageable. People in car crashes, people with cancer, pregnant women who have complications during delivery — all those people risk getting a lesser caliber of care when a hospital is trying to cope with the chaos of an outbreak.

“I think the whole notion of flattening the curve is to slow things down so that this doesn’t hit us like a brick wall,” said Michael Mina, associate medical director of clinical microbiology at Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital. “It’s really all borne out of the risk of our health care infrastructure pulling apart at the seams if the virus spreads too quickly and too many people start showing up at the emergency room at any given time.”

Countries and regions that have been badly hit by the virus report hospitals that are utterly swamped by the influx of sick people struggling to breathe.

Alessandro Vespignani, director of the Network Science Institute at Northeastern University, is gravely worried about what he’s hearing from contacts in Italy, where people initially played down the outbreak as “a kind of flu,” he said. Hospitals in the north of the country, which the virus first took root, are filled beyond capacity, he said, and may soon face the nightmarish dilemma of having to decide who to try to save.

“This was what was really keeping me up at night, to unfortunately see Italy approaching that point,” Vespignani said, adding that now that the country has effectively followed China’s example and put its population on lockdown, “hopefully this will work.”

Vespignani, along with colleagues, published a recent modeling study in Science that showed travel restrictions — which the United States has adopted to a degree — only slow spread when combined with public health interventions and individual behavioral change. He’s not convinced that people in the United States comprehend what’s coming.

“I think people are not yet fully understanding the scale of this outbreak and how dangerous it is to downplay,” he said.

Mina agreed: “Without a very clear signal coming from our government at the national level, it’s really just like a small trickle as people start to recognize that this is happening.”

This story was originally published by STAT, an online publication of Boston Globe Media that covers health, medicine, and scientific discovery.