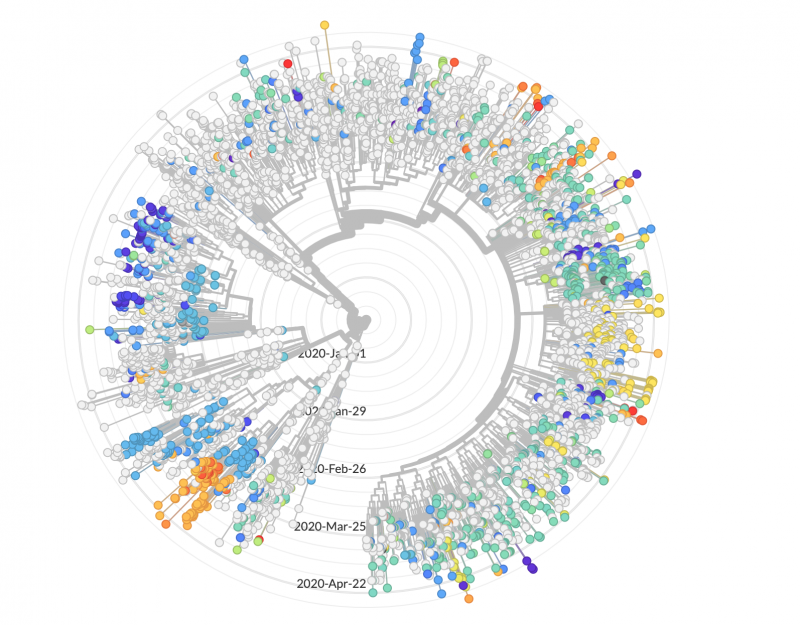

Genomic sequences suggest that the virus was introduced in the United States via multiple routes. Both Washington and California had early outbreaks. But some early California cases do not share the distinctive mutations of those in Washington, and likely arrived in the U.S. separately from China. In New York City, one of the nation’s worst-hit regions, the majority of cases are most similar to viruses circulating in Europe.

Tracking Outbreaks

As people relax their distancing, new outbreaks are all but assured. This nationwide sequencing effort, participants hope, will help with tracking and point toward undetected pockets of infection.

“A lockdown can never be perfect and there will be some pocket somewhere,” warns Peter Forster, a geneticist at University of Cambridge, who has published an analysis looking at genomes of the coronavirus in Europe and around the world.

As an example of how this tracing could work, imagine feeling sick and testing positive for the COVID-19 virus. You, or the public health department, alert all of your closest contacts. But to have the best chance of quashing the outbreak, health officials need to know where you got the infection. Here is where genomic sequencing can help.

Is your virus most similar to those circulating in New York? If so, perhaps you should tell your cousin who visited from Brooklyn that they should also quarantine for two weeks. Or does your virus have mutations most similar to those seen in Washington state? If so, it may be a different acquaintance, friend, co-worker or family member who should isolate themselves.

Spotting New Mutations, Guiding New Treatments

Stacia Wyman is a scientist participating in the CDC consortium at the Innovative Genomics Institute on the UC Berkeley campus, where they are analyzing patient samples for results. For every positive result the lab will try to sequence the genome of the virus in that patient. (In some cases, where the viral load is especially low, the genome cannot be accurately sequenced.) The information will illustrate which areas of the virus mutate quickly and which are slower to change. The slow-changing areas are ripe for attack.

“It is typical that in viruses or in genomes in general, even in humans, locations that have a very important function tend to evolve very slowly,” Wyman said.

In those certain locations, she says, if a mutation occurs it tends to cause disease or disrupt the function of the organism. (Viruses don’t quite qualify as organisms, but they do have genetic material and if they mutate in the wrong spot, they may not be able to replicate.) Those slow-changing areas are useful for scientists to identify, as they search for effective drugs or vaccines.

Drugs operate by taking aim at specific proteins and either interrupt the job they were going to do or mimic their effect. Proteins are the workhorses of the cell, carrying out the tasks of construction, destruction and replication. A gene codes for (in effect, writes the recipe for) a protein. If the gene sequence changes through a mutation, the shape of the resulting protein may also change. A drug targeting that protein may no longer work.

“And so when you have a therapy, it’s going to target a specific protein or region of a protein that’s going to target a specific locus [on the genome],” said Wyman. “And you want that to be very steady so that when you are coming up with a therapeutic, it is going to be effective for all individuals.”

Despite the steady accumulation of mutations in the genomes of the COVID-19 virus, initial signs are that the virus does not mutate too quickly to be addressed by a vaccine or therapeutic drug.

That’s good news for all of us.