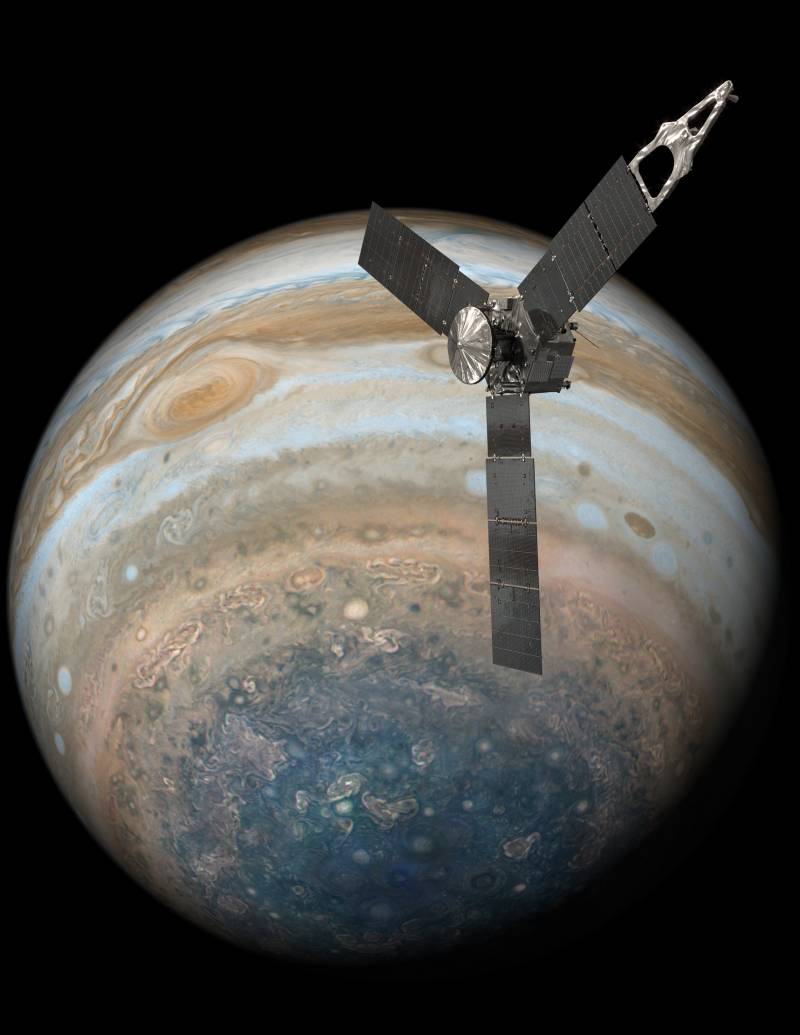

Four years after arriving at the planet Jupiter, NASA’s Juno spacecraft is still making fresh discoveries and sending us breathtaking pictures of the gas giant and its entourage of at least 79 moons.

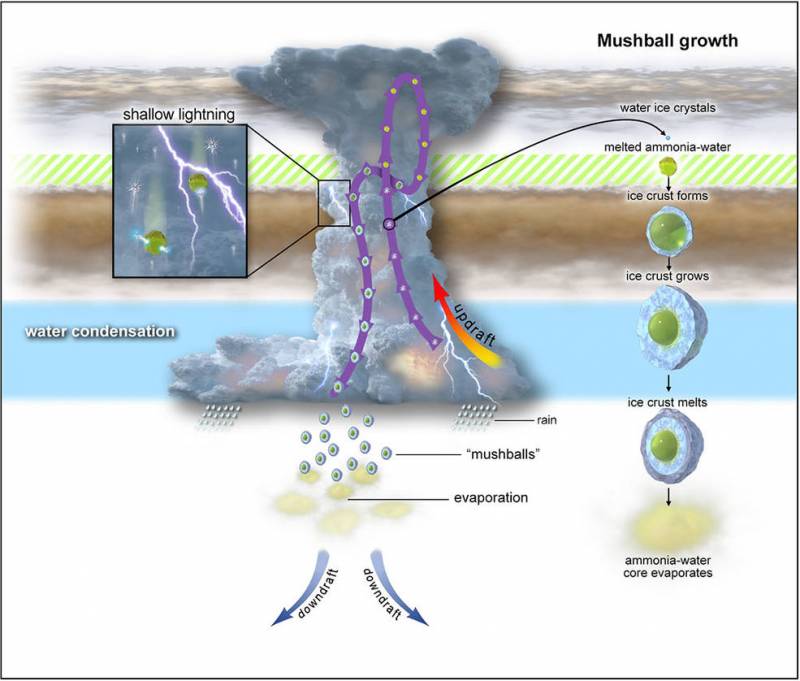

The most recent finding is a bizarre meteorological phenomenon, something not seen on Earth: “shallow” lightning, accompanied by slushy hailstones made of an antifreeze-like mixture of water and ammonia, dubbed “mushballs” by NASA’s Juno science team.

These mysterious weather phenomena have helped us better understand the distribution of ammonia in the Jovian atmosphere. And, they can help improve our overall understanding of distant planets orbiting stars in other solar systems, too far away for us to study in detail.

What Makes Lightning ‘Shallow’?

Since 1979, observations made by spacecraft before Juno — Voyagers 1 and 2, and Galileo — detected powerful flashes of lightning through the cloud layers of Jupiter’s turbulent atmosphere. Unlike Earth, the gas giant planet has no solid surface, and is made up of ever deeper and thicker layers of gas, mostly hydrogen and helium. The potent electrical discharges — detected by earlier missions — are believed to occur as far as 40 miles below the visible cloud tops, where temperatures and atmospheric pressure are right for the formation of lightning as we understand it on Earth.

On Earth, lightning is generated where water is found in all its states — gas, liquid droplets and solid particles of ice. Water vapor feeds the growth of liquid droplets in a cloud, and strong updrafts carry the droplets to altitudes where freezing temperatures turn them to ice particles. The ice particles fall downward, colliding with the upwelling liquid droplets, and the friction of their interaction knocks electrons from water molecules. Static electric charge builds up until it’s too strong to remain static, then discharges into the air, another cloud, or the ground. The same thing happens on a much smaller scale when you drag your shoes across a carpet and build up static electricity from the friction, until you touch another electrical conductor (metal, or another person) and discharge the electrons in a tiny, sometimes painful zap of mini-lightning.