Trash from humans is constantly spilling into the ocean — so much so that there are five gigantic garbage patches in the seas. They hang out at the nexus of the world’s ocean currents, changing shape with the waves. The largest is the North Pacific Garbage Patch, known colloquially as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

These areas were long thought to have been uninhabited, the plastics and fishing gear too harmful to marine life. But researchers have recently uncovered a whole ecosystem of life in this largest collection of trash. “This research has shown me that there is more life than we expected there … a whole ecosystem that are in the middle of the patch,” says marine biologist Fiona Chong.

OMG it literally took someone SWIMMING FROM HAWAII TO CALIFORNIA to discover this, but wow did we find something shocking in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch... [a thread 🧵]…

New study: https://t.co/kcbKyYJbXv pic.twitter.com/1hVL0YFbDp— Open Ocean Exploration (@RebeccaRHelm) May 5, 2023

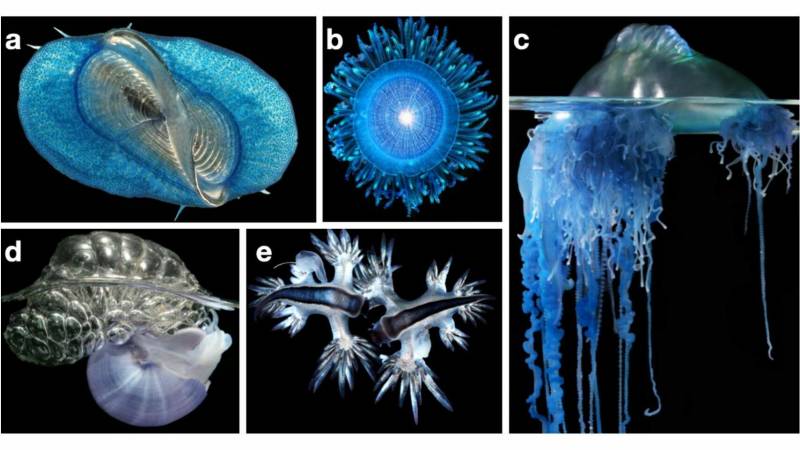

Fiona is part of a team of researchers that published a paper in PLOS Biology documenting the inhabitants of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch earlier this year. Their most common inhabitants include: Porpita (also called “blue button”), a small disc-like animal with “tentacles” radiating outward, closely related to jellyfish; Velella (also called the “by-the-wind-sailor”), which looks like a flat disc with a kind of “sail” running across the top; and Janthina a violet sea snail that traps bubbles to stay afloat. These and other organisms that float freely atop the water are called neuston.

Neuston form an ecosystem and food web amongst themselves. Janthina are known to eat both Velella and Porpita. Glaucus atlanticus, another neuston observed in very small quantities in the patch, is another predator. Known as the “blue sea dragon,” it prefers to snack on the Portuguese man o’war but has been known to chomp on both Porpita and Velella.

These marine animals are also are part of a larger ecosystem. Fiona notes that Porpita are known to sometimes form symbiotic partnerships with small, juvenile fish that are stressed when removed from their individual Porpita. Plus, animals like the ocean sunfish, seabirds and sea turtles are known to munch on neuston.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))