Giving names to newly discovered minerals is a sideshow in the carnival of science, like one of those booths where you toss a ball in a cup to win a stuffed animal. By that analogy, a team of scientists has won the giant stuffed panda, and the achievement was enough to rate a paper in the prestigious journal Science last week. They successfully identified the commonest mineral that makes up the Earth, and gave it the name of bridgmanite.

In various fields of science, insiders have the geeky privilege of awarding names to the things they discover. Astronomers can give names to new asteroids. Biologists get to name new species. Paleontologists get to name fossils. Even geneticists get to name genes. For instance, workers in all of these fields have used their privilege to honor the musician Frank Zappa (who died on this day in 1993).

And mineralogists get to name new minerals. Normally this is a pretty obscure deal because all the significant minerals have been named. The rules are clear: you have to find a sample in a natural rock, and you have to describe its crystal structure and its chemical formula.

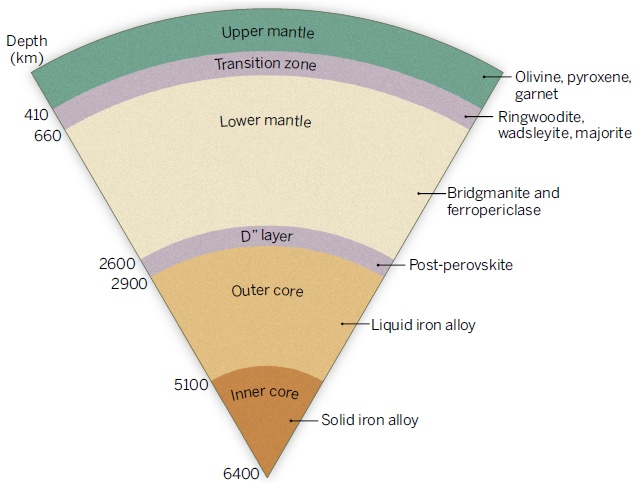

Bridgmanite was previously known by its description: magnesium-iron silicate in the perovskite crystal structure, or (Mg,Fe)SiO3-perovskite or “silicate perovskite” or, confusingly, just “perovskite.” (This can be confusing because real perovskite is the rare oxide mineral CaTiO3, and the common surface mineral orthopyroxene also has the formula (Mg,Fe)SiO3 but a different crystal structure.) It exists only under very high pressure, deep in the Earth’s mantle, and makes up more of this planet than any other mineral, about 38 percent.

We’ve known what it is for many years, and we’ve been manufacturing it in the lab, but by the rules of mineralogy we couldn’t call it by a simple name. One good way to find high-pressure minerals is to peek inside diamonds, which form at great depths and can trap tiny inclusions of other minerals inside them. Another is to find pieces of shattered planets—meteorites—and search for the bits that represent their high-pressure cores. Neither of these have worked for silicate perovskite.