We all stare at our teeth in the mirror, but when biologists brush their teeth they wonder how these unusual parts of our skeletons evolved. Now, a study combining the anatomy of fossils and the genomes of modern species argues that teeth have their roots in the skins of ancient fish.

A new paper published this week in the journal Nature may provide an answer. Researchers at Sweden’s Uppsala University and the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing searched for clues in fossils of an ancient line of fish that were the ancestors of the tetrapods, and in the genomes of those species’ closest living relatives.

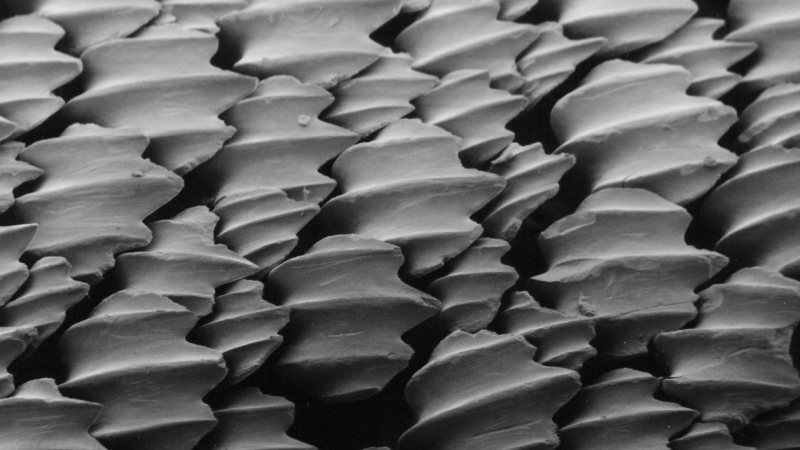

Fish have these mineralized tissues, too, but some have them in two places — in their teeth and in spines on their skin, known as denticles. These account for the texture of shark skin, rough when stroked in one direction and smooth in the other.

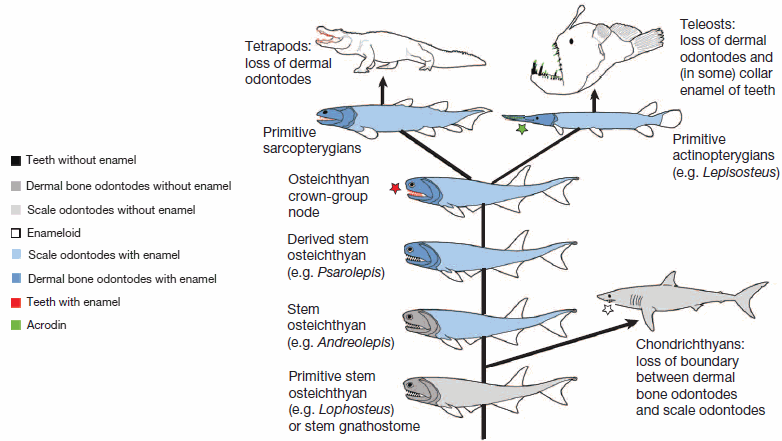

Between teeth and denticles, enamel presents a confusing set of clues. Modern bony fishes have teeth but no denticles, and their teeth are capped with a substance called acrodin instead of enamel. Sharks and rays, the oldest major class of living fishes, have both teeth and denticles, but they’re capped with a substance called enameloid instead of enamel.

Things get interesting in the handful of species between these two groups. The coelacanths, an ancient line of lobe-finned fishes related to the tetrapods, have true enamel everywhere.