“I’m the one who parked it there!” Jones recalls thinking. “Why can’t I remember?”

At work, he had a hard time finding the right words and making persuasive arguments to his colleagues. He’d come home and tell his wife, Anne, “Something’s different.”

“He would say his brain didn’t feel like it was working the same way it used to,” she recalls. “We said, ‘Well, why not talk to your primary care physician about it?’ And that started a cascade of events.”

Eventually, the Joneses made it to the Stanford Center for Memory Disorders, where Robin went through the standard run-up for Alzheimer’s disease, memorizing lists of words, and so on. But he did pretty well on them, says Mike Greicius, the center’s medical director, better than you’d expect from someone in the early stages of the disease.

“He didn’t fit neatly into this classic presentation of Alzheimer’s disease,” says Greicius. “That’s one of the reasons that, fairly early on, we started talking about biomarkers.”

These biomarkers refer to lab tests, and they’re a very recent development in Alzheimer’s disease care.

One test uses a PET scan that can detect amyloid, a protein that takes on an abnormal shape in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients. The second test requires a lumbar puncture to look for traces of amyloid and tau, another protein associated with Alzheimer’s disease, in the patient’s spinal fluid.

Robin chose the spinal fluid test. “It seemed to me it would sharpen up my understanding of what was happening,” he says.

Tests for Alzheimer’s disease signal changes across mental health

Until very recently, Alzheimer’s was diagnosed more or less the same way other mental illnesses, such as autism or schizophrenia, are diagnosed: by asking patients how they feel and observing how they behave.

That all changed when scientists discovered biomarkers for Alzheimer’s: the tau and amyloid proteins that are signatures of the disease.

Then, it was a matter of finding tests that could pick up those biomarkers.

Michael Weiner, who directs the Center for Imaging of Neurodegenerative Diseases at San Francisco’s VA Medical Center, says the same thing happened with heart disease a generation ago.

“When I was a medical student 40 years ago, patients would come in with chest pains and we’d spend a lot of time talking to them,” Weiner says. “‘Where is the pain in the chest? What’s going on? How does it radiate in your arm?’”

That whole process changed when scientists discovered biomarkers of heart disease, for example, certain enzymes that leak into the bloodstream when the heart is damaged.

“Nowadays,” says Weiner, “you draw blood enzymes. And if a person has a rise in certain enzymes, we say they had a heart attack. And if they didn’t, we say you didn’t have a heart attack.”

This is the name of the game in psychiatry today: to understand the underlying brain diseases behind mental illness and find ways to test for them.

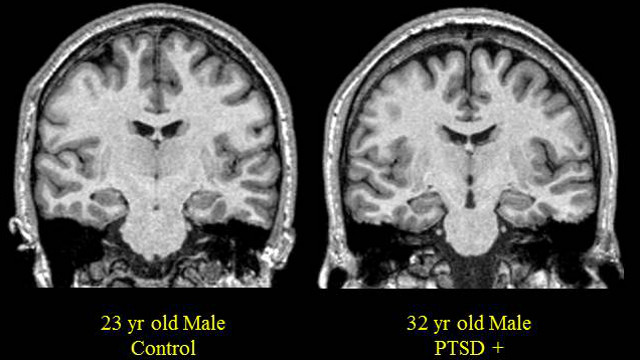

Better tools for diagnosing PTSD

One of the biggest efforts is directed out of NYU’s Langone Medical Center, where Charles Marmar chairs the psychiatry department and leads a $28 million dollar effort to look for biomarkers of post traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain damage, diseases that are often under-reported and under-treated.

Marmar believes that one day — maybe within a decade or two — simple tests, much like home pregnancy tests, will indicate whether people are suffering from PTSD or possibly even autism or schizophrenia.

“Blood, urine and cerebral spinal fluid will, over time, have something very important to say about risks for psychiatric illness, the presence or absence of illness and the prognosis of a given depressive illness,” says Marmar.

And, importantly, he says, whether a treatment – be it talk therapy or drugs – is working.

In the case of PTSD, he says, the first step is to look for biomarkers, what he calls the “biological footprint of learned fear,” that could be detectable in a lab test.

Voice as a diagnostic tool

But these diseases may announce themselves in other ways, too, for example, in the way people talk.

At SRI International, a non-profit research group in Menlo Park, scientists are developing computer algorithms to look for voice signatures of people with PTSD.

SRI’s Dimitra Vergyri plays a recording of three voices saying the word “no.” The first sounds disappointed, the second impatient, the third – with a happy laugh – sounds “entertained,” she explains.

“We want to show that there are features that we can extract automatically, measure them, and they can be an indicator of a very specific emotional state,” she says.

The idea here is that you could take voice recordings of, say, returning soldiers, and use the algorithm to flag which of them might be more at risk for psychological problems. Then, make sure they don’t slip through the cracks.

Charles Marmar, head of the NYU effort, believes tests like these will change the field of psychiatry.

“As we advance biomarkers, we will demystify and de-stigmatize psychiatric illness,” says Marmar. “We will make [mental health] part of normal care.”

The results come back

Slowly, that is what’s happening in Alzheimer’s disease, and in the case of Robin Jones.

Robin’s wife, Anne, was the first to learn the results of his Alzheimer’s test, which came back positive.

Her first reaction, she says, was simply sadness. But after that came “a certain amount of relief.”

“There’s relief knowing why your arm hurts, or why you have a bad cough. Knowing how to chart out the rest of our time together.”

Recently, Anne took a trip alone to Florence to see the great works of art she studied as an art history major in college. She left a note for Robin, reminding him where she had gone and thanking him for the opportunity.

Having a concrete diagnosis, she says, helped her recognize a window for such adventures, before her care-taking responsibilities begin to keep her closer to home.