This week in the journal Nature, a worldwide team of 75 scientists revealed the genetic blueprint of the one-celled alga Emiliania huxleyi, which may be the most important species you’ve never heard of. The genomes of the domestic dog and cat are interesting, but the E. huxleyi genome is a much bigger story. Some day this organism may become another of our partner species, as vital to us as yeast.

Oceanographers of all kinds know Emiliania huxleyi by the nickname “Ehux,” and that’s what I’ll call it too. Among the marine algae, Ehux is classified as a coccolithophore, so named because it builds loose shells around itself made of coccoliths. Coccoliths, in turn, are the intricate disks seen in the photo above at high magnification. The fate of Earth’s changing climate may ride on coccoliths.

In the world’s atmospheric carbon cycle, the ocean is ultimately in charge. And in the ocean’s carbon cycle, Ehux is a keystone species. To make coccoliths, Ehux takes carbon dioxide dissolved in seawater and combines it with calcium ions in the water to make calcium carbonate (the mineral calcite), somehow rendering its spiky crystals into shapes elegant enough to inspire new forms of pasta. CO2 from the air replaces what’s removed from the seawater.

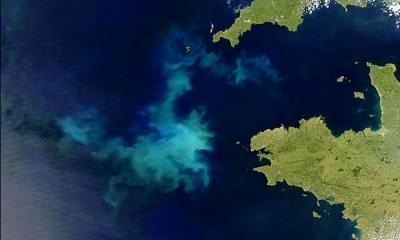

Coccolithophores are the single largest producer of biogenic calcium carbonate on Earth, and Ehux is their leading species. Ehux grows in every part of the ocean except around the frozen poles. It’s prone to enormous blooms—bursts of reproduction that may cover areas as large as California. Ehux blooms, with their uncountable numbers of coccoliths, reflect so much light that they turn the water a milky blue that is easily monitored by satellites.

Shed coccoliths drift down to the seafloor, and in favorable times in the geologic past they have formed beds of chalk. (The climax era of the dinosaurs, the Cretaceous Period, got its name from the thick chalk beds of Europe.) Chalk, and the coccoliths that compose it, represent carbon removed from the atmosphere.