Hundred-year-old trees are impressive, but thousand-year-old rocks may be more significant when looking for long-term climate clues.

On Monday, UC Berkeley soil scientists published evidence of growth rings on rocks similar to rings on trees.

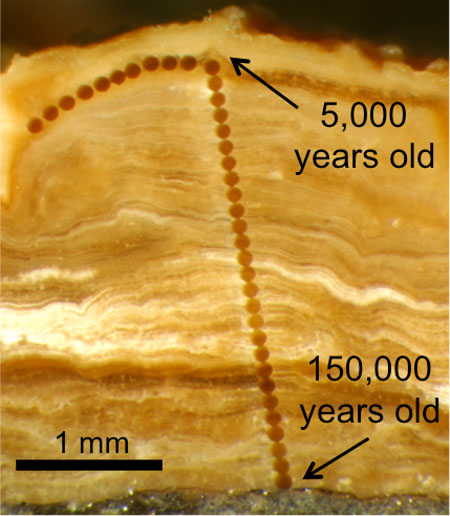

The scientists specifically evaluated soil that formed thin rings around gravel and pebbles. The deposits were so thin, in fact, that some were no more than 3 millimeters thick.

These carbonates in soil covering the rocks act as temperature and rain indicators.

“There is a mineral that accumulates steadily and creates some of the most detailed information to date on the Earth’s past climates,” says senior author Ronald Amundson, a UC Berkeley professor of environmental science, policy and management.

This detailed information covers 120,000 years in North America and includes glacial and interglacial periods during the Pleistocene Epoch.