Contrails—those cloudy tracks laid across the sky by jet planes—have a noteworthy effect on the local climate below, new research shows. A study recently published in the International Journal of Climatology suggests that in places where jets and their contrails are common, meteorologists could routinely add their effects to weather forecasts.

Contrails form wherever jets fly through the right atmospheric conditions. Water vapor in a jet’s exhaust condenses into water droplets or ice crystals, aided by microscopic seed particles from smoke, dust or pollen. The result is an instant cloud tracing the jet’s route through the air.

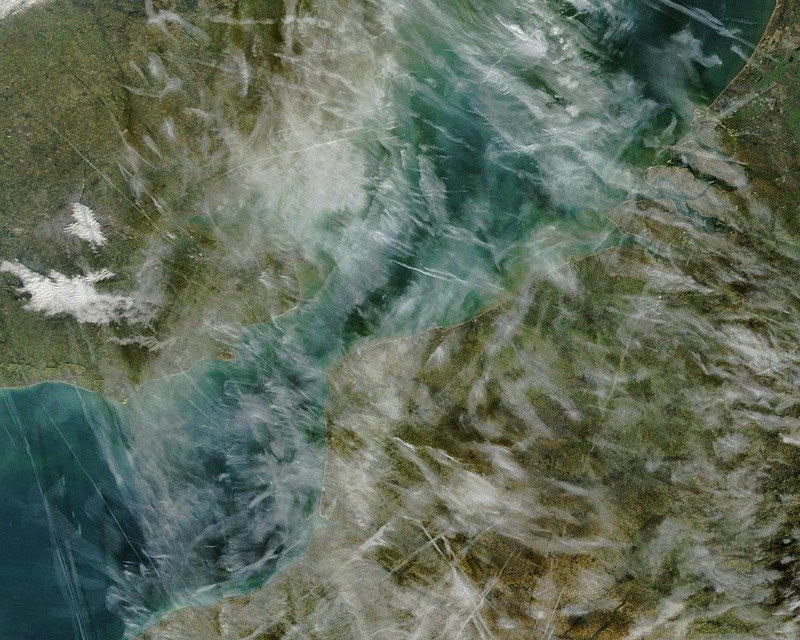

A contrail may evaporate quickly or persist for hours, depending on temperature and humidity conditions. Winds may smear it out. If enough contrails are present, they may combine into a thin carpet of high cloud.

Contrails are more than just a pretty sky feature or aerial annoyance. Scientists saw a dramatic example of their importance in September 2001, when the U.S. government grounded commercial airlines for three days in the wake of the 9-11 terrorist attack. During that time, areas that were prone to contrails, like the Midwest, had significantly warmer days and cooler nights.

The study’s authors, Jase Bernhardt and Andrew Carleton, are two atmospheric researchers at Penn State University who made a more systematic effort to study the effects of contrails on daily temperatures. They learned that contrail “outbreaks” have definite effects on ground temperatures, and those effects may be predictable.