As a student, Crum had spent years studying the placebo effect — how a sugar pill can physically alter a body if the person taking the pill believes it will. She figured food labels might work the same way. So she came up with an experiment.

Crum created a huge batch of French vanilla milkshake, then divided it into two batches that were labeled in two very different ways.

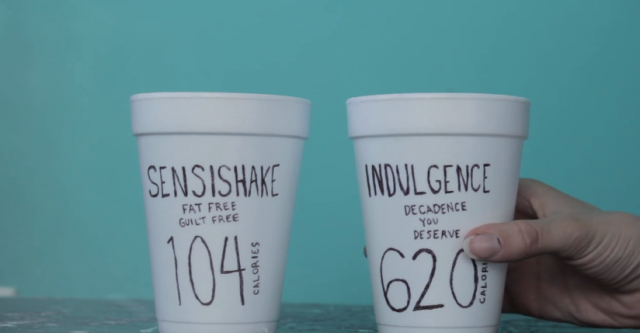

Half the stuff was put into bottles labeled as a low-calorie drink called Sensishake — advertised as having zero percent fat, zero added sugar and only 140 calories.

The other half was put into bottles that were labeled as containing an incredibly rich treat called Indulgence. According to the label, Indulgence had all kinds of things that wouldn't benefit your thighs — including enough sugar and fat to account for 620 calories. In truth, the shakes had 300 calories each.

Both before and after the people in the study drank their shakes, nurses measured their levels of a hormone called ghrelin.

Ghrelin is a hormone secreted in the gut. People in the medical profession call it the hunger hormone. When ghrelin levels in the stomach rise, that signals the brain that it's time to seek out food.

"It also slows metabolism," Crum says, "just in case you might not find that food."

But after your ghrelin rises, and you have a big meal (say a cheeseburger and a side of fries), then your ghrelin levels drop. That signals the mind, Crum says, that "you've had enough here, and I'm going to start revving up the metabolism so we can burn the calories we've just ingested."

On the other hand, if you only have a small salad, your ghrelin levels don't drop that much, and metabolism doesn't get triggered in the same way.

For a long time scientists thought ghrelin levels fluctuated in response to nutrients that the ghrelin met in the stomach. So put in a big meal, ghrelin responds one way; put in a small snack and it responds another way.

But that's not what Crum found in her milkshake study.

If you believed you were drinking the indulgent shake, she says, your body responded as if you had consumed much more.

"The ghrelin levels dropped about three times more when people were consuming the indulgent shake (or thought they were consuming the indulgent shake)," she says, compared to the people who drank the sensible shake (or thought that's what they were drinking).

Does that mean the facts don't matter, that it's what we think of the facts that matters?

"I don't think I would go that far yet," Crum says. More tests need to be done, she says, to figure out exactly how much influence comes from food and mindset.

But she does think the usual metabolic model — calories in and calories out — might need some rethinking, because it doesn't account in any way for our beliefs about our food.

"Our beliefs matter in virtually every domain, in everything we do," Crum says. "How much is a mystery, but I don't think we've given enough credit to the role of our beliefs in determining our physiology, our reality. We have this very simple metabolic science: calories in, calories out."

People don't want to think that our beliefs have influence, too, she says. "But they do!"

[contextly_auto_sidebar id="1prCSv6QOwemL45SzB6myMlDaf2mSMNn"]