For some it seemed like common sense. For others, it felt like government overreach and a restriction of freedom. In 2020, as the waves of a global pandemic broke on the shores of the United States and political discord raged within, mask-wearing for preventing the spread of COVID-19 became a polarized, hot-button topic. Although the effectiveness of face masks as a means of limiting transmission of the deadly virus became scientifically clear, political factions under the then-administration quickly took up sides – pro- or anti-mask. Former President Donald Trump repeatedly downplayed the seriousness of the virus and his supporters took offense to laws and mandates requiring mask-wearing and social distancing. Doctors and medical scientists scrambled to find ways to communicate to the public that the disease was serious and that mask-wearing was necessary not just to protect the wearer, but perhaps more importantly, to protect others.

This political polarization and resistance to established science was not new to science communicators – not even by a long shot. A cartoon began to circulate social media in which two medical researchers were having a conversation in a hallway next to two climate scientists. The medical researchers were saying, “As long as we just provide the facts to the American people …” The climate scientists are laughing hysterically.

Climate communicators, and science communicators working on a variety of subjects that have become politically charged, have been searching for decades now for ways to break through the polarization of public climate change concern. What if some of the communication techniques studied for climate change could be used to communicate with the public about the effectiveness and importance of wearing masks? What if they could even increase public support for mask-wearing policies? As part of the NSF-funded Cracking the Code project, researchers from Texas Tech University, Eckerd College, and Bucknell University attempted to do just that.

The researchers wanted to examine two specific techniques that have recently received a great deal of attention in the science communication community: consensus messaging and informative images, or, “infographics.” Consensus messaging is essentially telling people that scientists are generally in agreement that something is true. In the case of climate change, researchers show survey takers a simple statistic – 97% of climate scientists agree that climate change is caused by human activity. Some research has suggested that this is effective in helping people understand the severity of the issue and making them more concerned. Because this technique has not worked universally across different studies and topics, our researchers wanted to see if it would work for COVID-19 mask-wearing. This was a bit tricky, however, because we don’t have a simple statistic in this case. Instead, the researchers crafted a message stating that there is a “strong scientific consensus” that COVID-19 is dangerous and that mask-wearing slows transmission of the disease.

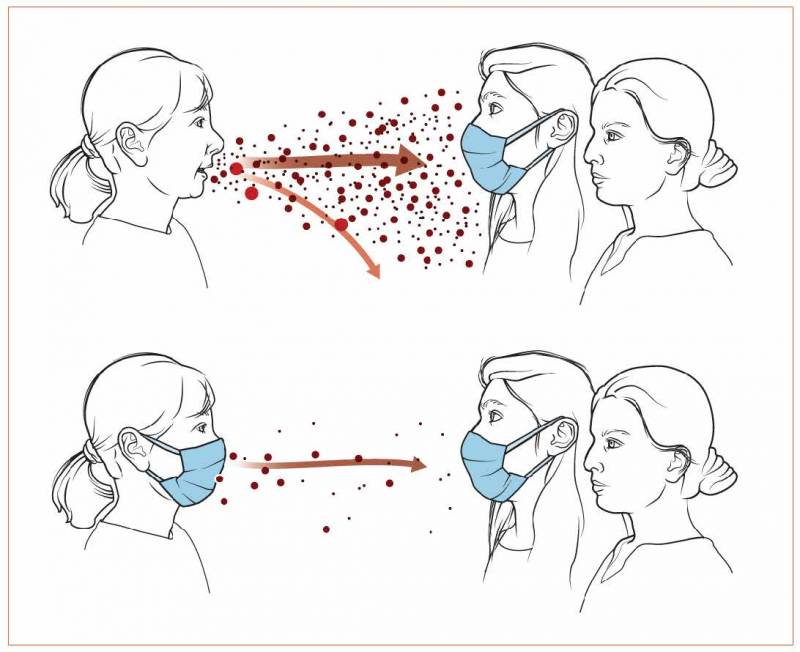

For the second technique, researchers used a graphic from the journal Science that depicts how masks prevent the wearer from spreading the virus to others. A nationally representative sample of 2,871 participants took the survey and were randomly served up different combinations of control messages, consensus messages, and the image. This study design, called a “modified Solomon group design,” split the sample so that some participants were contacted ahead of the full survey to gauge their concern and mask-wearing support before they saw the communication materials. Participants were asked about their support for different mask-wearing policies as well.

The survey results were interesting for a number of reasons. They helped us to better understand effective communication for mask-wearing, but they also showed us that the consensus messaging that some researchers have found works for climate change, didn’t appear to change public acceptance of mask-wearing or policies associated with masks. Here is a summary of the survey’s key findings:

- Presenting participants with a consensus message did not significantly influence their beliefs. Reading a scientific consensus message had no significant effects on participants’ perceptions of consensus, their beliefs about the effectiveness of mask-wearing for preventing the transmission of the disease, their risk perceptions of COVID-19 or their support for policies related to mask-wearing.

- The presence of an infographic depicting how masks help to prevent the spread of COVID-19 did, in some circumstances, influence participants’ beliefs. Participants who saw the explanatory infographic were more likely to agree that there is a scientific consensus that mask-wearing is an effective strategy for preventing the transmission of COVID-19, regardless of whether a consensus message was also present. This same finding held true for participants’ beliefs that masks prevent the wearer from contracting or spreading the disease. Participants receiving the image paired with the consensus message were more likely to support a policy that required employees in service industries to wear masks at work. These findings did not hold true, however, for the other two policy questions.

- Political party was the strongest predictor of participants’ beliefs about COVID-19 risks, mask-wearing, and policy support. Political party preference is the strongest predictor of perceived consensus, beliefs about the effectiveness of mask wearing, risk assessment of COVID-19, and policy support in both between-subjects and within-subject comparisons. Between-subjects tests showed that compared to Republicans, Democrats were more likely to perceive a scientific consensus that COVID-19 is more severe than the flu and that mask wearing is effective, are more likely to see the disease as risky, are less likely to see mask-wearing as risky and are more supportive of all three the mask-wearing policies across all conditions. Importantly, however, exposure to the image seemed to affect Republican participants.

You can read more about the survey design and the full report, called “Mask Messaging for COVID-19: Examining the Effectiveness of a Scientific Consensus Message versus an Explanatory Infographic” here and below. To learn more about the Cracking the Code project visit kqed.org/crackingthecode.