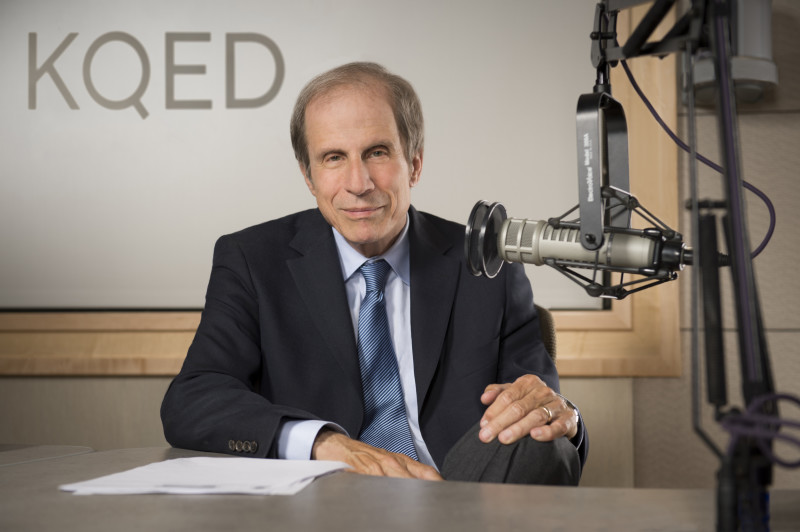

Twenty years ago, Václav Havel was elected president of the Czech Republic and Ruth Bader Ginsburg was joining the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, DC. Closer to home, 1993 was the year Professor Michael Krasny joined KQED as the host of Forum. Since then, the award-winning live call-in program has become the nation's most-listened-to locally produced public radio talk show.

This summer, Michael graciously took his turn as an interview subject. Unfortunately, live call-in wasn't available.

When you were interviewed in 1993 for KQED's member magazine, you said, "My work in radio started out as a hobby. I've always seen myself as an academic, not a broadcaster." Would you say the same thing today?

I think of myself primarily as a broadcaster and a professor now. But also as a writer. I don't know which one has hegemony. You talk to a lot of people who hate their jobs or can't find one thing that gives them pleasure or satisfaction or makes them feel they're making a difference. These all do that for me. It's a trinity.

And they all work so well together.

You're right. They are sort of in synchronicity with each other.

How did your radio "hobby" get started?

It started with television. In the 1970s, I did some interviews for public television, mainly of literary figures, and I did some commentary for Channel 2, KTVU news. But radio seemed like a better fit for me. I was lucky to just go into a little station in Marin, where I lived, and say, "Here's an idea for a talk show. You guys are all about music. Maybe you'd like to do something about public affairs?" And they went for it. It was a very unorthodox station in its day. What we used to call alternative radio. But the show got some attention. KGO expressed interest and I was there for a number of years. It wasn't a bad fit, but it wasn't really the right place for me like KQED is.