Image advisory: many of the Web sites linked to in this article contain photographs that are sexually explicit.

It is not entirely happenstance that the founding figure of the modern gay movement, Harvey Milk, was a photographer and the owner of a camera store. In the 1970s, the simple documentation of presence, the photographic equivalent of saying “we are here,” by itself assumed a progressive political cast for a population long freighted with the demand to remain both silent and invisible. At my current age of 55, I still remember the embarrassing sting of a film store’s refusal to process pictures of my 23rd (very gay) birthday party because the printer deemed the images “indecent.”

Queers had, of course, long been photographed, generally in the context of law enforcement, scandal, spectacle or satire. But in the 1970s, there emerged a new genre of queer photography that didn’t take pains to “other” its subjects, adopting instead a position of sympathetic witness. Anthony Friedkin’s photographs — especially his Gay Essay (1969-1973), now on exhibit at the de Young Museum in a show timed for the 45th anniversary of the Stonewall riots — assume exactly such a sympathetic stance. His pictures are notably quiet, neither triumphal nor suffused with pathos. And that, paradoxically, is why they are important — and why they were largely forgotten. In the years immediately after Stonewall, pictures of ordinary gay people leading ordinary lives were nothing short of extraordinary.

LGBTQ photography has changed and developed since then, along with the political movement that gave it birth. What follows is a list of largely West Coast LGBTQ photographers from Friedkin’s moment to the present. Collectively, their work can be read as a sensitive barometer to shifts in queer social life, revealing the turbulent political weather that has pushed queer identity into forms and guises unimaginable four decades ago.

Tress and Arnold: The Dream of Escape

Arthur Tress (born 1940), a photographer from New York who has spent much of his life in California, and Steven Arnold (1943-1994), a California artist, both cultivate in very different ways a photographic sensibility that casts Friedkin’s photos into high relief. Both are slightly older than Friedkin (who was born in 1949). Neither man’s photographs aspire to either contemporary relevance or to social understanding, opting instead for a kind of dreamy, surrealist timelessness.

But while Tress’ work pulls the viewer into a dream that turns on the psychic state of the photographer’s subject, Arnold’s leads the viewer away from the subject of the photo into a larger exploration of the viewer’s subjective responses. In Tress’ “Flood Dream,” for example, a young boy appears as an image of childhood alienation. As with so many Tress images of loneliness and displacement, the work suggests the psychic toll of social difference.

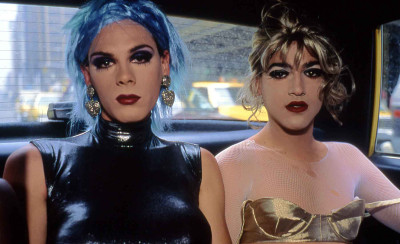

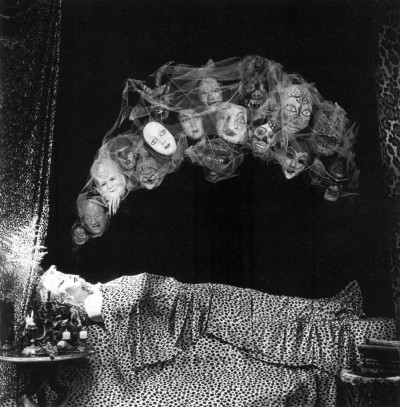

Arnold’s “Dreams of Transformation,” on the other hand, stages a palpably artificial performance to invoke a camp melodrama. Like much of Arnold’s work, the photo is a tableau vivant with a kind of queer subtext. The dreaming subject is a cipher, unreadable even as to whether she’s a woman or a man in drag. Queerness is present not in the form of a particular subject encountered on the street, as in Friedkin, but as an aura that suffuses everything.

Tee Corinne and the Landscape of Womanlove

Tee Corrine (1943-2006), an influential artist based in Oregon, also resisted the impulse toward photojournalism, yet she managed to adhere to an ethic of reportage.

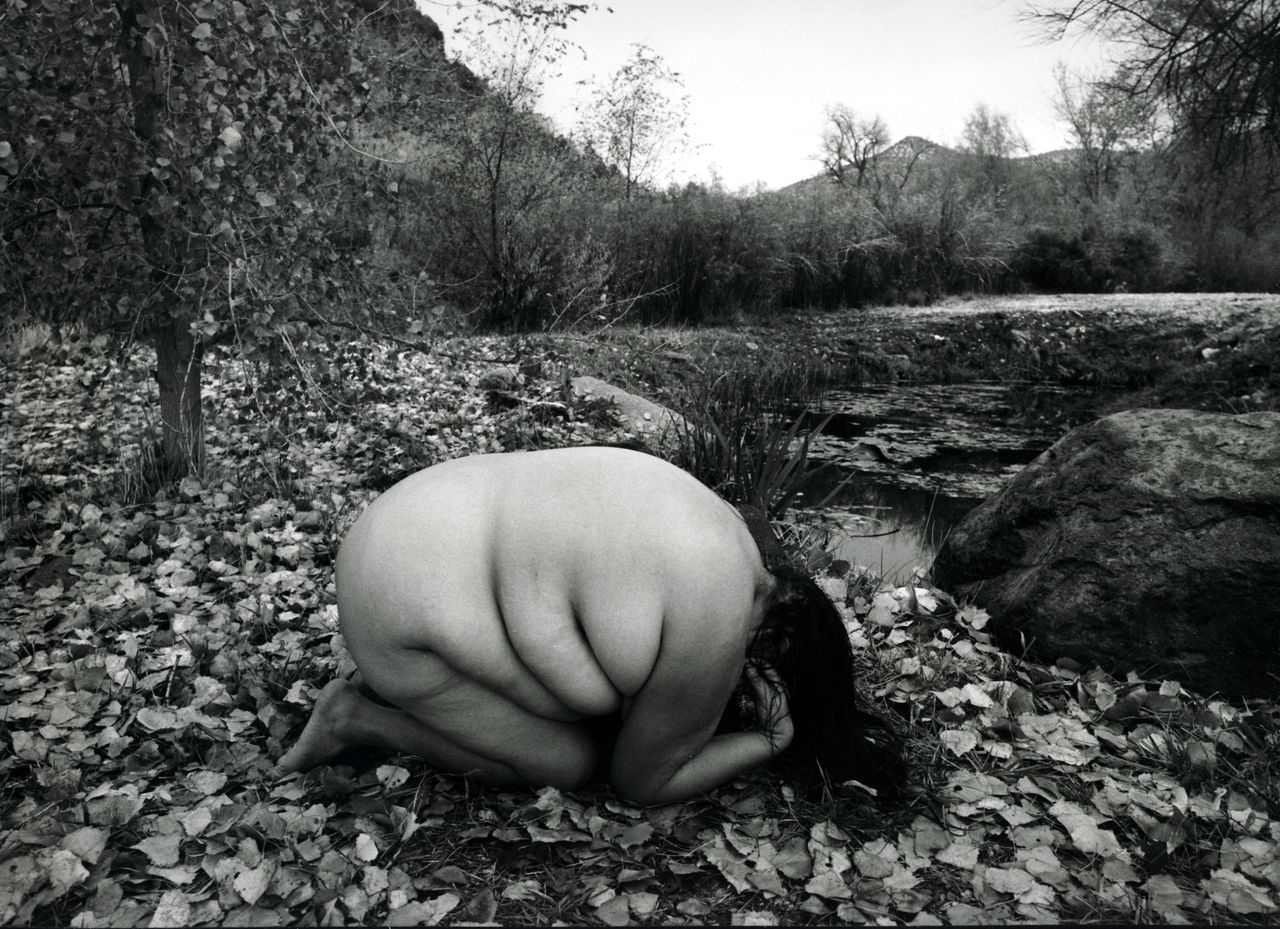

A pioneering photographer, art historian and advocate for a specifically lesbian visual culture, Corrine was well aware of the danger that images of women together might serve the pleasure of a heterosexual male gaze. To frustrate that unwelcome attention, she used processes like solarization and double exposure to make images that offer the outlines of women’s faces and bodies, while robbing them of the specificity required for an erotic charge. Her nudes resist the confines of conventional beauty while opening onto a seductive picture of female sexual self-determination.

Corinne is perhaps more famous as the author of The Cunt Coloring Book, which invited women to color line drawings of genitalia and to draw their own vaginas and the vaginas of their friends. In some of her photographs, she places images of vaginas seamlessly within undomesticated landscapes, implicitly gendering Mother Nature according to familiar tropes, but also suggesting a wild femaleness that cannot be tamed.

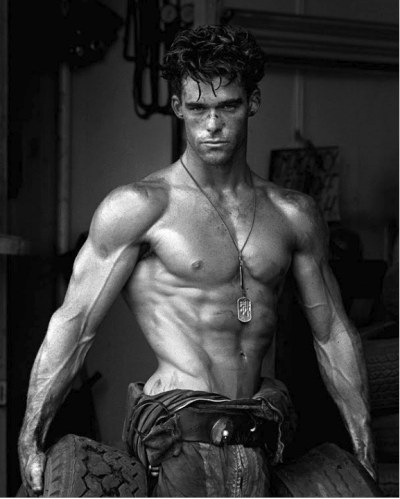

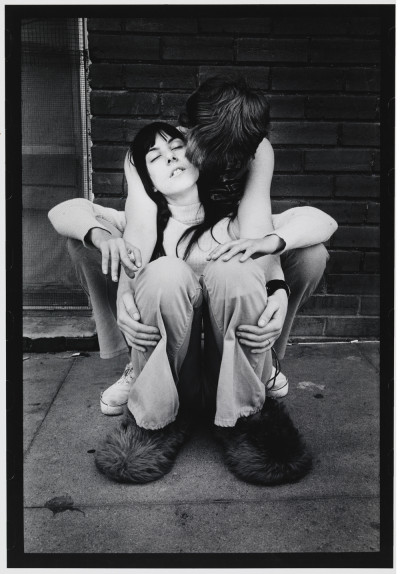

Marsha Burns: Manufacturing Masculinity

Marsha Burns (born 1945) parted ways with the mythopoetics of Corrine’s equation of femininity with nature and fecundity in a series of images of masculinized women she began making in the early 1980s.