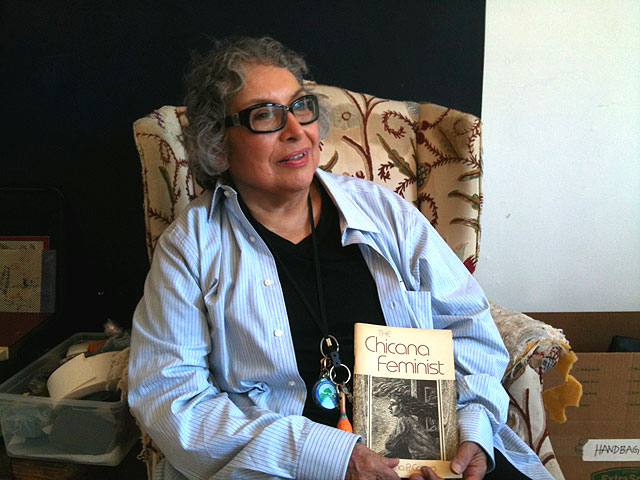

On a warm Sunday in San Francisco, as the city celebrated Pride weekend, longtime Mission artist Yolanda M. López put her recent Ellis Act eviction on display. The event at Red Poppy Art House, titled Accessories to an Eviction, was a conceptual performance-slash-garage sale organized to streamline the artist’s possessions in anticipation of vacating her home of forty years. It was the second such sale of things she liked and had cared for over the years. Everything was whole, with no chips or stray threads. It was also an immersive, participatory conceptual art performance organized to complicate distinctions between the personal and the political.

As I wrote recently in an article for the San Francisco Chronicle, López was a leading feminist and pioneer of the Chicana art movement in the ’60s and ’70s. Though never a commercial success, her work is included in the collections of several major institutions, including the de Young, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Oakland Museum of California. She was also an adjunct professor for decades at many esteemed Bay Area colleges, including UC Berkeley and Stanford. Now at 71, she subsists on social security, the sum of which is too little to qualify for low-income housing. As she prepares to leave her home in the Mission, she is making art out of her eviction.

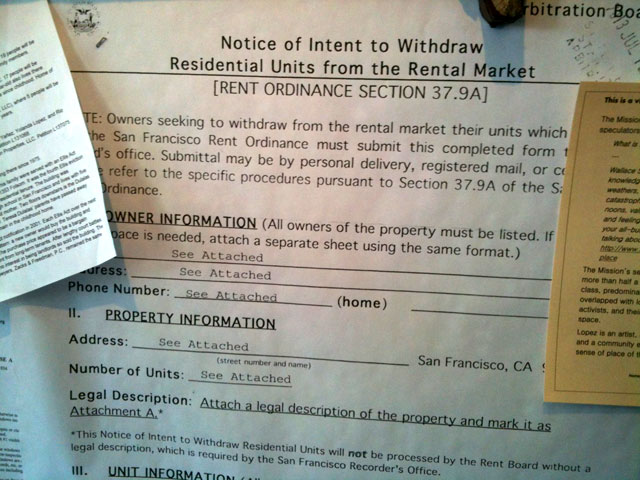

The concept for López’s eviction garage sales is inspired by friend and mentor artist Martha Rosler’s 1973 Monumental Garage Sale. Items for sale included a cache of vintage neckties, jewelry, and pocketbooks, among other accessories. Each item was tagged with a price. Each was also labeled with a second tag that read: “ACCESSORIES To An Eviction” The Mission, 2014, Yolanda M. Lopez.

In the buyer’s hands, each object was transformed and the buyer was free to decide its fate. Was this a practical object? Was this a found artwork? In either case, the answer is the same. Yes, these were practical objects. And yes, these were found artworks and documents of the event.

As a kind of performance, it was a gut wrenching display. I was reminded of the public vulnerability of Yoko Ono’s 1964 Cut Piece. Captured in grainy video, the artist knelt on a stage while audience members were invited to cut away her best clothes. In Cut Piece, much is left to the viewer’s discretion and every gesture is freighted with meaning, including how much is cut away, and from where. The participant’s demeanor was indicative of something too: compassion, empathy, entitlement, or the lack thereof.