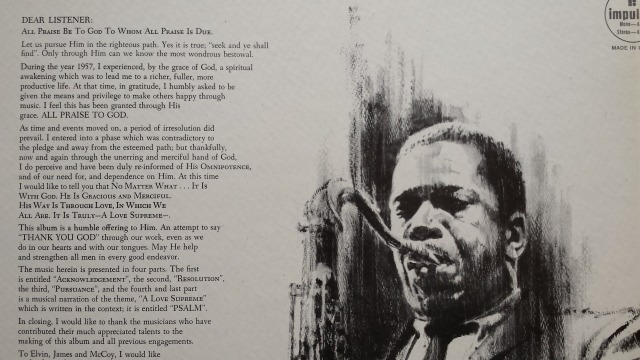

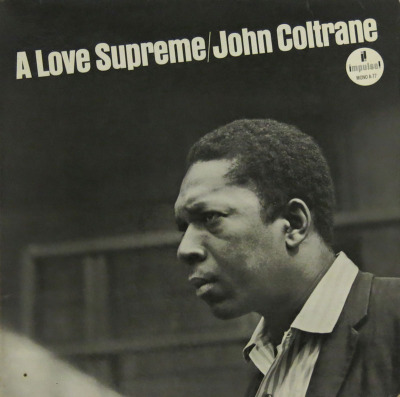

Even the album’s cover photo is unforgettable – and a bit jarring. Is John Coltrane angry? In pain? Contemplative? A Love Supreme is one of the most recognizable, most successful and most influential jazz albums in history. Recorded in 1964, it’s Coltrane at his best, a milestone piece of art that set a new standard for jazz language, and is to music what Joyce’s Ulysses is to literature or Scorcese’s Taxi Driver is to film.

In four parts that last 33 minutes, Coltrane’s album ascends scales with verve and intensity, moving from intimate note-making and soulful introspection to, as in the third part called “Pursuance,” all-out explosions of fury and finality. Coltrane devoted the album to God, but A Love Supreme can be understood by any listener, from any culture, as a journey of discovery. The highs are there in abundance, but so too are the stops and starts and transitions – the mesmerizing transitions – that lead to the journey’s end. Salvation doesn’t come without struggle. Beauty is found in dissonant notes. Generations of music-lovers and musicians, including Carlos Santana and U2’s Bono, have embraced A Love Supreme as divine music.

From Wednesday to Sunday (December 10-14), SFJAZZ is celebrating the 50th anniversary of Coltrane’s album with six major events that pay homage to Coltrane’s vision and its continuing influence on the world of jazz. Coltrane’s saxophone-playing son Ravi, named after the Indian sitarist Ravi Shankar, is featured in the first five events, starting with a Wednesday symposium (Dec. 10, 7:30pm) at the SFJAZZ Center that also features Ashley Kahn, author of the must-read 2002 book, A Love Supreme: The Story of John Coltrane’s Signature Album. When I interviewed Ravi Shankar in 2002, he remembered meeting Coltrane in the 1960s and finding “turmoil” in Coltrane’s music. The turmoil, Shankar said, was disturbing.

But in re-listening to A Love Supreme for Kahn’s book, Shankar rethought this view and told Kahn he found the album “beautiful, especially the climax in the third movement (“Pursuance”), then the resolution of the whole last piece (“Psalm”).”

“Psalm” does, indeed, resolve A Love Supreme, with drummer Elvin Jones, pianist McCoy Tyner, and bassist Jimmy Garrison all joining Coltrane’s saxophone in a sustained and gripping convergence that lasts seven minutes. The intensity of A Love Supreme can be challenging for first-time listeners. Coltrane died in 1967 at age 40, and his last three years of recordings, when he veered into more and more ecstatic music, are Coltrane at his most fervorous. In Live in Seattle, which was recorded in 1965, Coltrane and saxophonist Pharaoh Sanders frequently employed “squawking” – bursts of atonal riffs – that turned off many of Coltrane’s earliest fans. As a bandleader, Coltrane’s most accessible album is My Favorite Things from 1961; the title song plays with the signature tune from The Sound of Music.