Until February 5, 2015, you can visit the main branch of the San Francisco Public Library and be momentarily transported through space and time to the early days of the Exploratorium via the life and work of Bob Miller, who died in 2007.

The transportation isn’t entirely complete, especially when unavoidable elements of the library’s physical space interrupt the installation of vitrines, wall text and objects. But reading first-hand accounts by Miller’s colleagues of his various contributions to both the Exploratorium and scientific discovery, I wished I’d wandered the museum with him at any point in his twenty year tenure. Documentation and ephemera will never be as entertaining as the man himself, but Light Walk: Bob Miller and the Exploratorium presents one man’s creativity, playfulness and lasting impact on an institution, leaving the viewer itching for the simple tools of his trade: sunlight, paper and an irrepressible curiosity.

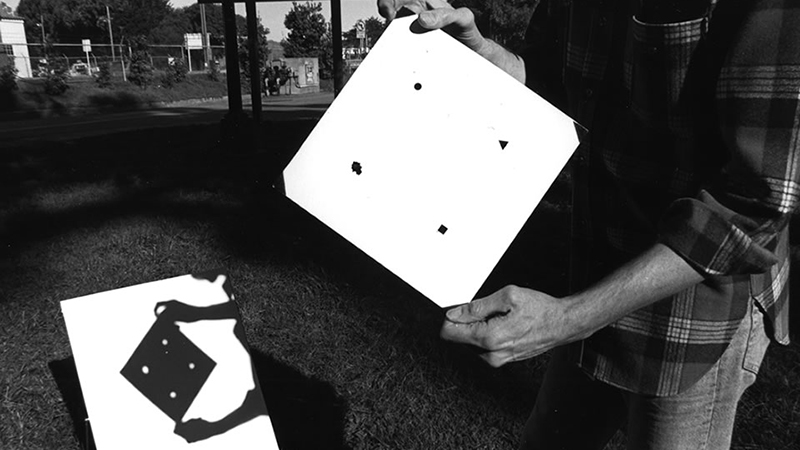

Light Walk is installed on the library’s fourth floor, rubbing elbows with the art, music and recreation collections. Four large cases present short anecdotes about Miller and related materials from the Exploratorium archives: photographs, magazine clippings, patent documents and museum publications. The bits and pieces coalesce into a picture of Miller — much like his Light Walk, an exploration of sunlight, shadow, refraction and perception builds on basic demonstrations to build a larger understanding of the natural world.

Before he met Exploratorium director Frank Oppenheimer in 1970, Miller lived a number of lives. Roaming from the White Sands Proving Ground to India and the South Pacific, he worked in the Army, for IBM, as a postal carrier and merchant marine. After this Renaissance man lifestyle, he helped shape the Exploratorium for nearly two decades, in its exhibits and its ethos.

Peter Richards, another longtime Exploratorium colleague whose name might be familiar as co-creator of The Wave Organ, details the development of one of Miller’s signature exhibits. Richards depicts a fledgling institution where getting an NEA grant for the construction of Sun Painting’s mechanically-mounted mirror is as simple as a letter from Oppenheimer to the federal agency. A prevailing attitude of “we think this might work, let’s find out what happens” makes these early days at the museum seem thrilling.