I was six years old when the Atari 2600 game E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial was released. In the years since, the game has taken on an almost mythical quality in the hearts and minds of many Atari fans, not as something wonderful, but as something so awful (so the story goes) that it was largely responsible for the 1983 collapse of the video game industry.

This notion always bothered me, because to my six-year-old self, E.T. had not been an awful game at all. Broken and frustrating, sure, but also distinctive, ambitious, and most of all, emotionally resonant in a way most games weren’t. You win the game by phoning home and boarding the ship back to E.T.’s home planet, but this victory always seemed bittersweet to me, because it meant saying goodbye to Elliott, who you would then see, in his home, alone. I’d played games that were exciting, or scary, or whimsical, but E.T. was the first game I played that felt poignant.

Within a year of the game’s release, Atari was all but gone.

Because of my fondness for E.T. and my interest in Atari’s history, the documentary Atari: Game Over is essentially made for me. Filmmaker Zak Penn, also a lifelong Atari fan, sets out to discover the story of E.T.’s creation and find out just what role it played in causing the video game crash of 1983. While excavating the truth of Atari’s past, Penn also pursues a more literal excavation in the vast landfill of Alamogordo, New Mexico, where Atari was rumored to have buried perhaps millions of E.T. cartridges it had produced but could never hope to sell.

The film bounces back and forth between these two strands, but despite the tremendous symbolic power in the act of attempting to literally unearth the past of a once-massive and beloved company, the scenes focused on organizing the landfill dig sometimes get bogged down in talk of red tape and excavation equipment, making them feel like a detour from the real story. And some sequences, like one that follow Ernest Cline (author of the video-game-themed novel Ready Player One) as he cruises in a DeLorean with a full-size E.T. figure in the passenger seat, are so self-indulgently geeky and packed with so many pop-culture references that they diminish the film, sending the message that you’re either in on the joke or that this story is not for you.

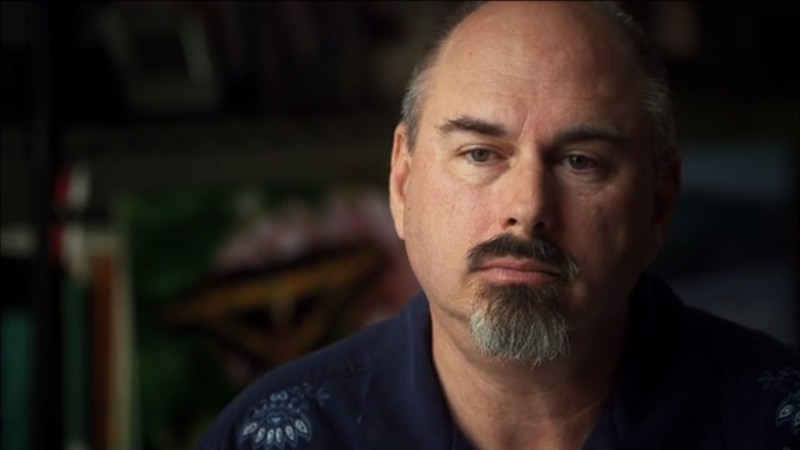

And that’s too bad, because the story of Atari, and specifically of E.T.’s designer and programmer Howard Warshaw, is a fascinating one that you don’t need an existing interest in video game history to appreciate. Warshaw comes across as a smart, complicated, likable man, and by focusing on him, Penn makes the story of Atari’s downfall a human story rather than just a story of reckless business decisions and massive financial shortfalls.