I loved Hotline Miami.

Hotline Miami felt to me like the sort of game Michael Mann might have made in the early 80s, if he’d gone into designing video games instead of directing films like Thief and producing TV shows like Miami Vice. The neon visuals searing my retinas, the exceptional electronica soundtrack propelling me forward, I tore through its levels in an adrenaline-fueled rush. The presence of every individual enemy got my pulse racing to an almost uncomfortable degree, because in the blink of an eye, any one of them could end my life.

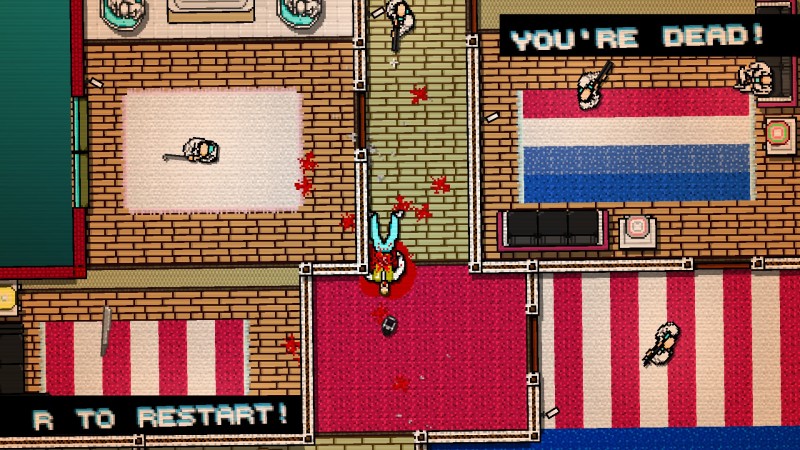

It was kill or be killed; each time I stepped out from behind cover to take a shot at one or to charge at one from behind, my body tensed up because of the huge risk I was taking, and each time I successfully shot or hacked or beat one of them into a bloody mess, I felt a little jolt of satisfaction as I stopped holding my breath for a moment before preparing myself for the next kill. With each mangled enemy corpse, I was one step closer to getting out of there alive. A lot of games are all about killing, but Hotline Miami’s combination of stylish graphics, incredible music, twitchy, risk-heavy gameplay, and brutal violence added up to an experience that made killing in games feel newly exhilarating.

At the time, I told myself that the intensity of the violence in Hotline Miami was a good thing. When you kill the last enemy in a level, the music stops, and you’re left alone amid the carnage you’ve caused. You have to walk back through the levels to get to your car, and without the threat of instant death lurking around every corner, the adrenaline starts to dissipate and you’re confronted with the horror of your own actions. At least, this is what I told myself, as a way of perhaps making myself feel better about the fun I was having, or as a way of convincing myself that the game was operating on some deep, meaningful level. Then I went on to the next level and enjoyed the adrenaline rush that came from slaughtering the next bunch of gangsters.

We like to think that games that feature violence as a core mechanic can be critical of violence, and in fact a piece was recently published on Paste Magazine called 10 Violent Games That Comment on Violence. (Hotline Miami is on the list.) But I no longer think it’s possible for a game that sets out to be fun and entertaining, in which violence is the primary way or the only way available to you of solving problems and interacting with the world, to do anything but glorify and celebrate that violence.