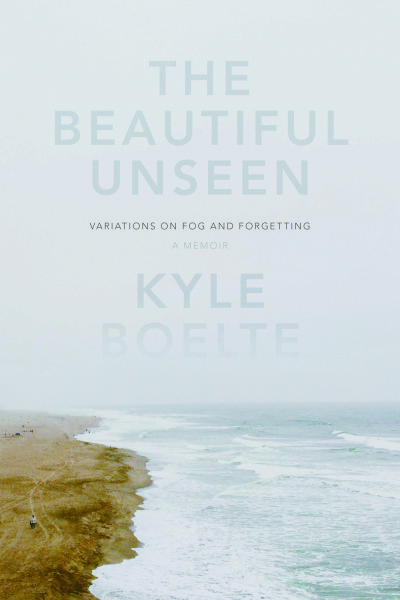

When you live in this city, the desire to bestow meaning on fog is inescapable. I’ve done it. I’ve heard others do it, too. In his debut memoir, The Beautiful Unseen: Variations on Fog and Forgetting, Kyle Boelte dresses up fog with the qualities of remembrance. In this book, the improbable story of hunting for fog merges with that of searching for memories of a deceased brother.

The story is slow to build. Boelte weaves instances of hiking toward fog between historical tidbits (ships run aground by fog, the discovery of the Bay belated by fog), and he combines all of these with the dreary scenes in 1993 when Boelte’s father descends to the basement in the family’s Denver home to check if his eldest teenage son is down there. It is beautiful writing. See the chilling way Boelte describes that day in 1993:

Dad’s steps on the stairs are slow and deliberate. He is walking down the stairs. Now he is in the basement. He is screaming now. The world is crumbling in on us. The rafters are being pulled down by your weight.

Mom is dialing 9-1-1. She is talking to the dispatcher. The dispatcher asks if someone can cut you down. It does not matter, though. You have faded.

The writing is nuanced and delicate. This is a memoir, though, with so many tributaries that some of them come off as mis-directions (the history of Golden Gate Park, for example, doesn’t quite seem to fit, and a childhood memory about exploring a storm drain pipe is thrilling but abstract). If not from this, the story is definitely frayed by the complete inclusion of documents that don’t really add anything new to the narrative. Boelte says more in prepping the introduction of these documents than the documents say on their own (the lyrics to “Come Out and Play” by the Offspring hardly needed full printing, ditto an e-mail from Boelte’s parents, and a high school speech written by Kris Boelte, the author’s older brother).

Due to the multi-directionality of his narrative, Boelte finds himself in the role of tidying up its forward movement by reintroducing again and again the idea of a dual journey to searching for fog and memory. After the initial stutterings, however, the book is an upswell.

Boelte goes out with a scientist, Dr. Burns, who is trying to find a way to predict fog. In relating the elusive nature of her task, she gives the example of the marbled murrelet, a seabird that hunts in the Pacific and lays one egg on a branch of a redwood tree. The fact of the egg escaped scientific observation until the 1960s. “So much still remains out of sight,” Dr. Burns tells Boelte, and that much seems to apply to everything. While the research put into this book strikes me as superficial, and one comes away knowing only bits and pieces about fog and Boelte’s lost brother, I admire the nebulous structure of the telling.

There is a poignant, brilliant point in the book, when as Boelte finishes going through a box of his brother’s belongings, one turns the page, and is haunted there by a chapter heading number, and then four pages of white. I love this book for this reason alone. The risks Boelte takes are beautiful, even if he doesn’t quite get away with them.